by Claire Chambers

In my last blog post I wrote about starting to learn the Hindi language during the pandemic. I embarked on this linguistic journey partly from a sense I didn’t fit into my own culture – or, equally, that English culture wasn’t the right fit for me. The sociologist Edward Shils wrote in 1961 about pre-Second World War visitors returning to their South Asian lands after a long time in Britain only to feel a ‘lostness at home and homesickness for a foreign country’. This is something I can recognize, albeit in the opposite direction.

In my last blog post I wrote about starting to learn the Hindi language during the pandemic. I embarked on this linguistic journey partly from a sense I didn’t fit into my own culture – or, equally, that English culture wasn’t the right fit for me. The sociologist Edward Shils wrote in 1961 about pre-Second World War visitors returning to their South Asian lands after a long time in Britain only to feel a ‘lostness at home and homesickness for a foreign country’. This is something I can recognize, albeit in the opposite direction.

As I became an intermediate learner, it felt as though my progress was glacially slow. In the early stage, every new word is a milestone. Yet once a solid linguistic framework already exists, forward momentum may be hard to discern. The learner can no longer see the yardsticks measuring progress as easily as they could at the outset.

The beginner may have a blithe innocence about the size of their task. However, the more you know, the more you realize you don’t know. I read somewhere, on the Berlitz website perhaps, that it takes five years to learn a language. It depends on what you mean by learn. Almost three years in by now, I would question that cheery five-year prognosis. I am caught in the middle of a process that feels never-ending.

At the start I hadn’t apprehended I would be setting myself up for lifelong learning. I do now! Second language acquisition requires patience, dedication, and a willingness to challenge yourself and make mistakes. Yet a price can’t be put on the rewards of being able to communicate and connect with others in their own language. And we don’t often moan about losing our fitness if we stop exercising or getting dirty if we neglect our personal hygiene tasks.

There is still a long way to go before I’d be considered fluent in Hindi. The intermediate level is often regarded as the most difficult stage of language learning. I’ve experienced so many plateaus that it feels as though two tectonic plates have smashed together in my head. I already have a good practice regimen, but know I’ll need to work smarter in order to reach an advanced level.

Some days it goes quite well. On others I hear wrong word after wrong word coming out of my mouth, powerless to stop them. Or I hit all the right notes, but not necessarily in the right order. It’s important not to forget that this sort of thing happens in the first language too. Everyone has days of feeling less articulate than usual – tongue-tied or hesitant, unable to find a bon mot. We’re just more likely to turn it inwards when it comes to a second language.

I thought of Malcolm Gladwell’s famous maxim about it taking 10,000 hours to get good at something. Remembering this, I listened to an abridged translation of Gladwell’s book Outliers: The Story of Success on GIGL (‘Great Ideas, Great Life’). Then, on a similar platform called Kuku FM I found a related volume he wrote entitled The Tipping Point.

GIGL and Kuku FM are apps offering audiobooks in Hindi. Many of their books belong to the self-help genre, like my personal bugbear Rich Dad, Poor Dad. I loathe Robert Kiyosaki’s ubiquitous volume based solely on its patronizing title and the neoliberal, anti-education summary. Besides this nemesis, I recommend other lowbrow audiobooks as ideal for intermediate learning. What might enrage you for its misleading certainty in the mother tongue has a soothing simplicity in a second language.

Meanwhile, a widely available podcast entitled ‘Learning Hindi on the Go’ focuses on conveying grammatical quirks and explaining cultural nuances. Listening to your second language is a great intermediate tip I can give you. Passive exposure to the language each day – regardless of whether the source is highbrow or bakwas – aids in making its cadences, pronunciation, and lexicon familiar.

grammatical quirks and explaining cultural nuances. Listening to your second language is a great intermediate tip I can give you. Passive exposure to the language each day – regardless of whether the source is highbrow or bakwas – aids in making its cadences, pronunciation, and lexicon familiar.

Despite enjoying Gladwell’s books (as far as I could understand them in their Hindi renditions), I soon found that the author has been critiqued. Counter-research says it’s not only about putting the hours in but also working with a good teacher. I’d agree with this correction, particularly because I’ve encountered quite a few amateur tutors whose only qualification is that they’re native speakers. A sound educationalist sends you on the right path, but the wrong one can lead you astray.

I also half-remembered a compound word from my days learning German: Sitzfleisch. In my head, this is an instruction: Sit on your meat! The more hours you put in, the more you’ll get out of what you’re doing. To be precise, the noun means ‘backside’ or ‘iron butt’! The portmanteau comprises part of sitzen (to sit) and Fleisch (meat). The phrase kein Sitzfleisch haben translates as ‘to have no staying power’.

There is thus a lot to be said for being present: putting bum on seat, so to speak. Without a fuss, make the language part of your everyday routine. To switch metaphors, Somali novelist Nuruddin Farah has said: ‘Languages are like knives … you use them; if you don’t sharpen them well enough, they get rusty, and like blunt instruments, they don’t serve you well’. Even as you make countless errors, you’re still sharpening your knife for better enjoyment of your Sitzfleisch.

Language learning isn’t only about work. Over time, it becomes fun, pleasure, and compulsion. For the Bengali-American novelist Jhumpa Lahiri, learning Italian is about ‘the desire to speak it every day, to plunge into a new idiom, to encounter new people and a new culture’. ‘Plunge’ is just the right giddily littoral verb, so it’s no surprise that they call intensive linguistic study ‘immersion’. I had to joyfully drown myself; to be willing to make mistakes, take risks, and ultimately be baptised and reborn.

Language learning isn’t only about work. Over time, it becomes fun, pleasure, and compulsion. For the Bengali-American novelist Jhumpa Lahiri, learning Italian is about ‘the desire to speak it every day, to plunge into a new idiom, to encounter new people and a new culture’. ‘Plunge’ is just the right giddily littoral verb, so it’s no surprise that they call intensive linguistic study ‘immersion’. I had to joyfully drown myself; to be willing to make mistakes, take risks, and ultimately be baptised and reborn.

Like Lahiri, I now judge a day to be unsatisfactory if I can’t use my new language. I seek every opportunity, forcing the dhakghar-wali (‘postmistress’) at our local GPO to chat to me in Hindi even though she’s happier in her mother tongue of Punjabi. I’m downcast when the waiting staff in The Star of India speak Bengali and only have a few recognizable phrases drawn from Star TV’s Bollywood offerings.

Slowly I was finding the Hindi Subject-Object-Verb word order becoming more natural. Plus, an enabling feature of contemporary Hindi is that if you don’t know a word, inserting the English term into the appropriate part of a sentence often works equally well. I’ll talk more about this phenomenon of Hinglish in a future blog post (I told you last time I was likely to get carried away with this and related topics!).

As for reading, I was starting to see why flashcards are such a popular method for teaching children literacy. Repeatedly seeing the shape of words in a new script is helpful for capturing them in![]() the mind’s eye. In his book Fluent Forever, Gabriel Wyner argues that a computerized version of flashcards known as spaced repetition systems (SRSs) is one of three secret weapons to long-term language success for adults. ‘SRSs are flash cards on steroids’, he writes, going on to argue that they ‘supercharge memorization’. Inspired, I asked one of my Gen-Z sons for help using Anki. He had used the free software while revising for GCSEs, and I now turned it towards nailing postpositional phrases. (Wyner’s other two trump cards are practising pronunciation first, and ditching translation so that you achieve complete engrossment in the target language. I take all three with a pinch of salt, but Wyner’s perspective is refreshingly clear and opinionated.)

the mind’s eye. In his book Fluent Forever, Gabriel Wyner argues that a computerized version of flashcards known as spaced repetition systems (SRSs) is one of three secret weapons to long-term language success for adults. ‘SRSs are flash cards on steroids’, he writes, going on to argue that they ‘supercharge memorization’. Inspired, I asked one of my Gen-Z sons for help using Anki. He had used the free software while revising for GCSEs, and I now turned it towards nailing postpositional phrases. (Wyner’s other two trump cards are practising pronunciation first, and ditching translation so that you achieve complete engrossment in the target language. I take all three with a pinch of salt, but Wyner’s perspective is refreshingly clear and opinionated.)

In The Murder at the Vicarage, Agatha Christie writes about ‘reading a word without having to spell it out. A child can’t do that because it has had so little experience. A grown-up person knows the word because they’ve seen it often before’. Christie’s Miss Marple draws an analogy between ‘grown-up’ reading and a detective’s powers of intuition. But the comparison cuts both ways. Sleuth-like, the more reading I did, the easier it was to decipher Devanagari.

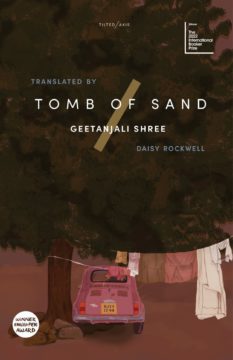

Left to my own devices, I wouldn’t read enough Hindi. This is due to my natural indolence and because even a few pages of Devanagari still tends to give me a headache. That’s why I’ve found regular Zoom reading groups so enabling during this intermediate stage. My ambition before too long is to read at least some of Geetanjali Shree’s International Booker-winning Ret Samadhi (Tomb of Sand) with a few friends from around the world who are at a similar level.

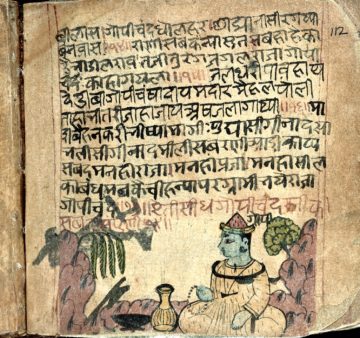

Although it is quite hard to master, once memorized Hindi’s alphabet is phonetic and has none of English’s pesky exceptions to trip you up. Devanagari has been described by Elizabeth Chatterjee as resembling ‘the laundry of a big-boned family: thick square sleeves, starched collars and blocky socks, all dangling from the washing line in familiar left to right fashion’. The historian’s comic portrayal nicely indicates the way Hindi’s letters seem to hang off the upper horizontal line known as shirorekha.

Although it is quite hard to master, once memorized Hindi’s alphabet is phonetic and has none of English’s pesky exceptions to trip you up. Devanagari has been described by Elizabeth Chatterjee as resembling ‘the laundry of a big-boned family: thick square sleeves, starched collars and blocky socks, all dangling from the washing line in familiar left to right fashion’. The historian’s comic portrayal nicely indicates the way Hindi’s letters seem to hang off the upper horizontal line known as shirorekha.

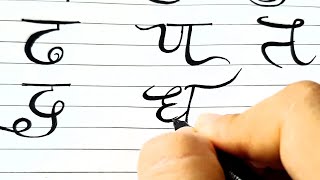

This alphabet is wildly attractive, though to my mind not quite as beautiful as the swoops and swirls of Urdu’s Nastaliq script. My favourite Hindi letter is kh, ख, whose plump body and sharp beak somehow reminds me of Twitter’s bird logo, but facing the other way.

That said, of the forty-eight letters, there’s a bevy of pretty ones to choose from. I am also fond of symmetrical k, क, perky as a smart moustache. There’s an allure to austere n, न, looking down its snout at the unwary learner. Laidback ch, छ, with its ghungharali curliness, has an exuberance making it hard to forget.

Sidebar: my colleague, the erudite polyglot James Williams, tells me that the form of Devanagari used for Sanskrit has a whole letter that doesn’t actually exist anywhere in the ancient language. Sanskrit grammarians had to include this for phonetic completeness. It is ॡ, the long form of vocalic ‘l’.

On the other hand, among the common letters I felt resentment for s (स), m (म), and bh (भ), as towards errant triplets tricking me into confusion through their similarities. Twins व (v) and ब (b) are a pain in the Sitzfleisch too. Why couldn’t they look more different? I bemoaned – until I voyaged into Urdu, which I’ll write about in detail next time. If Perso-Arabic is unsurpassably handsome as calligraphy, Devanagari has a more diverse and interesting character set. There are fewer letters in Hindi that are basically variations on the same letterforms (as in Urdu’s خ ح ج , ب ت ث پ, and so forth).

More generous were अ and आ, the first letters Duolingo taught me. I called the pair ‘three-I’ and ‘three-I-I’ while learning that they make the sounds ‘a’ and ‘aa’ respectively. The d, द, was kindly too, looking as it does so much like the English lowercase character it shares a sound with. र is good in this way, looking just like the right hand side of the capital R (as exploited so nicely by the rupee symbol, ₹). ज always feels like a J. Moreover, प and P are clearly mirror images, with their backs to each other. It’s strange the kind of personal relationships one develops with symbols, humanizing them or turning them into hieroglyphs.

More generous were अ and आ, the first letters Duolingo taught me. I called the pair ‘three-I’ and ‘three-I-I’ while learning that they make the sounds ‘a’ and ‘aa’ respectively. The d, द, was kindly too, looking as it does so much like the English lowercase character it shares a sound with. र is good in this way, looking just like the right hand side of the capital R (as exploited so nicely by the rupee symbol, ₹). ज always feels like a J. Moreover, प and P are clearly mirror images, with their backs to each other. It’s strange the kind of personal relationships one develops with symbols, humanizing them or turning them into hieroglyphs.

Next, let me give you a flavour of the distinctiveness of spoken Hindustani and some of the ways it is remaking my world.

In my last essay I noted that this is a gendered language. Now I need to really labour the point. Hindi takes genders to an extreme, with even infinitive verbs being inflected as masculine or feminine in some situations.

Determining the gender of inanimate objects in Hindi is an intractable challenge that has puzzled learners through the ages. A student shared a tale with me about their Hindi teacher, a mother of two, who was stumped when asked for tips and tricks. The teacher tried in vain to find a pattern amongst everyday objects. She had to admit defeat and concede that it just takes practice. But here’s the thing. The teacher shared that her little daughter, growing up with an older brother, had picked up the habit of using masculine pronouns and terms of address for herself. She had to be taught out of the practice, as it was making adults laugh at her. Apparently imitation in this way is a process that a lot of younger children with siblings of the opposite gender undergo. It is a comical reminder that even native speakers make mistakes. More than that, language is always evolving. It will therefore be interesting to see what happens to Hindi this century as gender non-binary pronouns become normalized and increasingly popular around the globe.

My feminist self was quite pleased to find bhukamp (earthquake), toofan (storm), korona virus (Covid-19), and some other destructive forces of nature being gendered as masculine. Languages like Hindi and English (angrezi) are automatically feminine, which I found quite positive. In many Indo-European languages, the feminine gender is allocated to abstract concepts. No such simple rule applies to Hindi, where for example the common suffix -pan, meaning -ness or -hood (as in bachpan, ‘childhood’ or akelapan, ‘loneliness’) renders the noun masculine. However, many other negative nouns like barh (flood) and aapda (disaster, calamity) are gendered feminine. In truth, there might be good feminist reasons for wanting some badass fierce things, like floods and other disasters, to be feminine so that the gender isn’t only associated with soft appealing words.

My feminist self was quite pleased to find bhukamp (earthquake), toofan (storm), korona virus (Covid-19), and some other destructive forces of nature being gendered as masculine. Languages like Hindi and English (angrezi) are automatically feminine, which I found quite positive. In many Indo-European languages, the feminine gender is allocated to abstract concepts. No such simple rule applies to Hindi, where for example the common suffix -pan, meaning -ness or -hood (as in bachpan, ‘childhood’ or akelapan, ‘loneliness’) renders the noun masculine. However, many other negative nouns like barh (flood) and aapda (disaster, calamity) are gendered feminine. In truth, there might be good feminist reasons for wanting some badass fierce things, like floods and other disasters, to be feminine so that the gender isn’t only associated with soft appealing words.

With that being said, some of the female members of Hindi University rightly complain about the feminine associations given to the half a dozen or so words that exist in Hindustani to denote a problem or difficulty. (What a lot of words for the same negative thing, when it can be tricky to explain the subtleties of positive emotions and qualities in Hindi.) The femininity of this plethora of problem words is consistent, no matter whether the nouns’ roots come from Persian, Arabic, or Sanskrit. Pareshani, mushkil, samasya, kathinta, and dikkat. It seems that the age-old association of woman with trouble and strife is alive and well in Hindi gendering.

There is also an inherent sexism in other ways. For instance, masculine is always the default if gender isn’t known or a postposition or ‘ne’ blocks the grammatical subject. Man is the standard; woman is a deviation from the norm. What’s more, I was taught to talk about my husband in the plural for respect, as in Ve daktar hain, ‘They are a doctor’. When I found out ‘they’ only had to use the singular pronoun for me, I chose to exert videshi or foreigner’s privilege and refuse this convention to pluralize him. One’s more than enough.

An unusual feature is that Hindi assigns genders to English words. I’ve already hinted that even a new word like ‘coronavirus’ is quickly given a gender, in this case masculine. To take older examples, ‘computer’ is masculine but ‘bus’ is feminine. While the gendering of absorbed terms may be arbitrary, it is also relational and holds true for the whole of India’s Hindi belt.

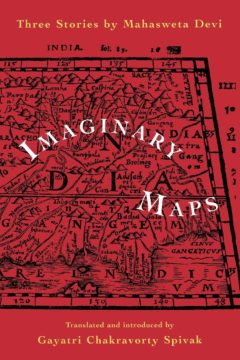

The infiltration of English words into Hindi tells quite the story of violent colonialism. Small wonder that when translating Mahasweta Devi’s Imaginary Maps from Bengali into English the renowned postcolonial theorist Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak chose to italicize these loanwords, which include policeman, officer, and jail. This not only had the effect of domesticating Bengali while foreignizing English, but also drew attention to English’s acquisitive and disciplinary infiltration into the South Asian subcontinent.

The infiltration of English words into Hindi tells quite the story of violent colonialism. Small wonder that when translating Mahasweta Devi’s Imaginary Maps from Bengali into English the renowned postcolonial theorist Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak chose to italicize these loanwords, which include policeman, officer, and jail. This not only had the effect of domesticating Bengali while foreignizing English, but also drew attention to English’s acquisitive and disciplinary infiltration into the South Asian subcontinent.

In her ‘Translator’s Note’ to Geetanjali Shree’s Tomb of Sand, Daisy Rockwell discusses the process of transforming the lyrical soundscape of Hindi into English. Rockwell writes that Shree:

In her ‘Translator’s Note’ to Geetanjali Shree’s Tomb of Sand, Daisy Rockwell discusses the process of transforming the lyrical soundscape of Hindi into English. Rockwell writes that Shree:

relishes the sound of words, and how they echo one another, frequently showcasing their dhwani—a word that she points in the course of the novel is among the hardest to translate. But let’s try. Dhwani is an echo, a vibration, a resonance. It is alliteration and assonance. Dhwani could be deliberate and playful, as in double entendre and punning, an accidental mishmash of sameness, or a mystical reverberation. Geetanjali often makes word choices that prioritize dhwani over dictionary meaning. Wordplay takes on a life of its own in many passages and sometimes even drives the narrative.

Not only Shree but also Hindi-speakers more broadly strive for creativity in the sound of words and how they complement each another. A ludic enjoyment of language’s musicality above and beyond meaning leads to the delightful badinage that is encoded within Hindi. The language is known for its repetition and echo words. This last is a technique of rhyming or putting together words that sound similar. Examples include: milta jilta (this phrase itself meaning ‘similar’!), aas pass (nearby), and khana wana (food). These words are used for emphasis, and sometimes (but not always) they have meaning. For instance, choti bari cheeze means ‘small and big things’, while the half-rhyme of bhul chuk indicates a mistake or some silly things I’ve done. New echo words are invented by individuals or carried over into other languages than Hindi. I remember a sleepover party from childhood when a diasporic friend’s mother used English to satirize us teenage girls for our obsession with ‘love-shove’. Such echoes can produce pathos bathos and nudge sentences to end in a silly or serious way. Translating these words to English can be slippery. The daft ones often start with ‘w’, like chai wai (tea), pani wani (water), and coffee-woffee. Repetition is deployed to describe extremes: how great things are or how bad, as with bade bade (very big) or choti choti baate (tiny things). Some echo words are formed by repeating participles, like chalte chalte, which imparts the sense of constantly doing something. This wordplay is my favourite aspect of Hindi; it makes for comedy, for poetry, for sheer lexical exultation.

Compared with individualistic English, in Hindi you often don’t do or have things but instead they befall you. Liking, knowledge, and memories all come to you in Hindi (Mujhe pasand aya, and so on). To quote Chatterjee again, in this context ‘we humans are mere ants facing a powerful and hostile world/our passions/loose bowels’. You don’t drop a cup; the cup has fallen. You didn’t break your arm. Why would you do that? It was broken. You don’t have a car; instead, the car is near you, in your proximity. Lateness happens to you. It’s not your fault!

In my early intermediate phase I used to bristle when teachers would chide me for using hai or ‘is’ with main or ‘I’. Main hoon, they’d trill: ‘I am’. Thinking about how often I had to use hai/is with mujhe/to me, I’ve concluded this wasn’t my fault either. The mistake came fully-formed to me from Hindi.

I have spent my entire academic career writing on students’ work: ‘Don’t overuse the passive voice. It allows you to evade specificity. Instead, pin down who did what to whom’. Hindi teaches something different. My new friend and fellow 3QD writer Leanne Ogasawara emailed me about how English, her mother tongue, compares to her second language, Japanese:

Linguists might say that using the passive voice does not really change the way a person goes through the world, but somehow I felt for me it did . . . Another way to say this is that when I first came home from Japan and heard people speaking in English, all I heard was “I want”, “I like”, I feel”, and also expressions which seemed full of blame. Someone did something to someone. . . Now, I don’t notice so much, but I still wonder if these linguistic ideas don’t affect our worldview . . . We have cut off ourselves from notions of Providence, but the truth is: so much is out of our control and things really do happen to us! I love the passive construction . . . I love the conditional even more, but in creative writing in America at least it is a big no-no. Nothing is qualified and it makes you feel so atomized in English. For me, part of the pure joy of Japanese was getting outside my preconceived notions.

Leanne’s musing on the passive voice and conditional forms in language paints a vivid picture of the transformative power of a new language, revealing how it can shape our perceptions of the world and liberate us from tired conventions.

As I continue to learn and grow in my knowledge of Hindi, I’m grateful for the opportunity to step outside my culture and deepen my understanding of this fascinating tongue. I’m excited to see where my journey will take me next and determined to keep striving towards fluency in Hindi. Maybe one day I’ll find myself in a strong enough position to write you a blog about being an advanced learner.

I am not passively caught in the middle. Instead I am here, in the middle of the language, having caught something. Whether a contagion or a ball, you can decide. All I’ll say on the matter is howzat!