by Akim Reinahrdt

Time slips

past us, fast flow,

like a river rushing over gray stones

Time drips

slower than slow

like thick sap hanging from pine cones

I’m not sure time is real. I mean, things happen. Entropy and whatnot. But I don’t know if I accept that measuring the pace of happenings is anything more than a construct.

Don’t get me wrong. I know the world is round, or a close approximation thereof. I’m down with the science. But physicists, as a group, aren’t united on what time is. Something about time being “measured and malleable in relativity while assumed as background (and not an observable) in quantum mechanics.”

So while we experience it as real, it may not be “fundamentally real.”

And that’s kinda how it feels to me.

I remember my 6th grade English teacher, Mrs. Newman (Ms. was not to her liking), telling us that the older you get, the faster time goes by. I’m not sure why, but that idea immediately clung to me. Though I was only 11 years old, or perhaps in part because of it, I got what she was saying. And I believed her. After all, she had lived four or five or six times (who could tell) as long as I had. So even though what she was describing sounded like a cliché passed on from generation to generation, I assumed her own experiences had borne it out. During the four and a half decades since, I have always remembered her words and noticed that, in a general sense, she was absolutely correct. Back then, a summer was endless. Now, the years roll on like a spare tire picking up speed down a hill.

But that is a historical observation I make as I look back. My present, like everyone else’s, stretches and squeezes like an accordion. Read more »

I recently binge-watched all of

I recently binge-watched all of

The Balkans isn’t everybody’s first choice for summer holiday, but that’s where we’re headed this year. First we’re flying to Chișinău, while we still can, and I don’t mean to be flip. Forgive my wavering confidence in Western guarantors of freedom, democracy and territorial integrity.

The Balkans isn’t everybody’s first choice for summer holiday, but that’s where we’re headed this year. First we’re flying to Chișinău, while we still can, and I don’t mean to be flip. Forgive my wavering confidence in Western guarantors of freedom, democracy and territorial integrity.

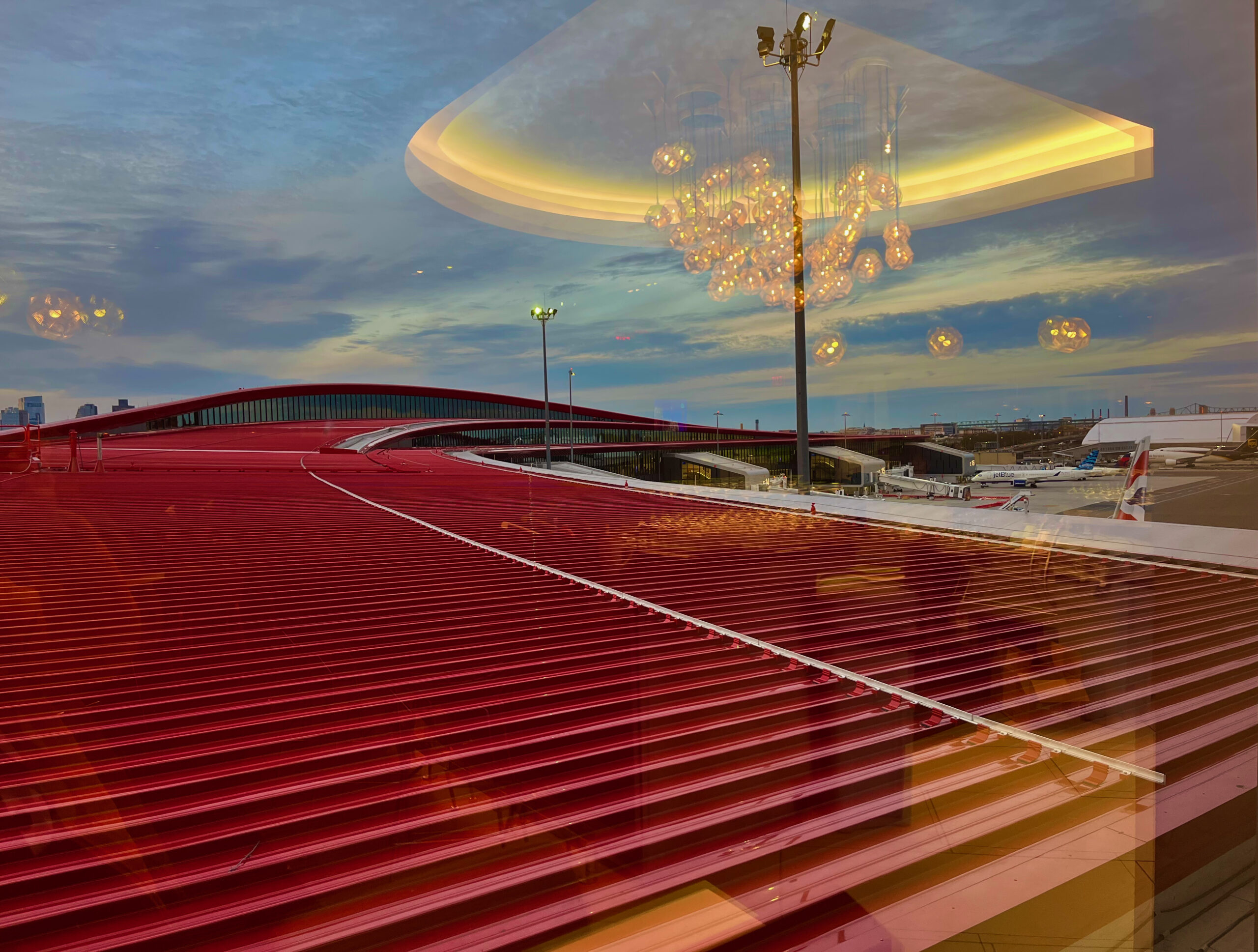

Sughra Raza. New Wing. November 2023

Sughra Raza. New Wing. November 2023

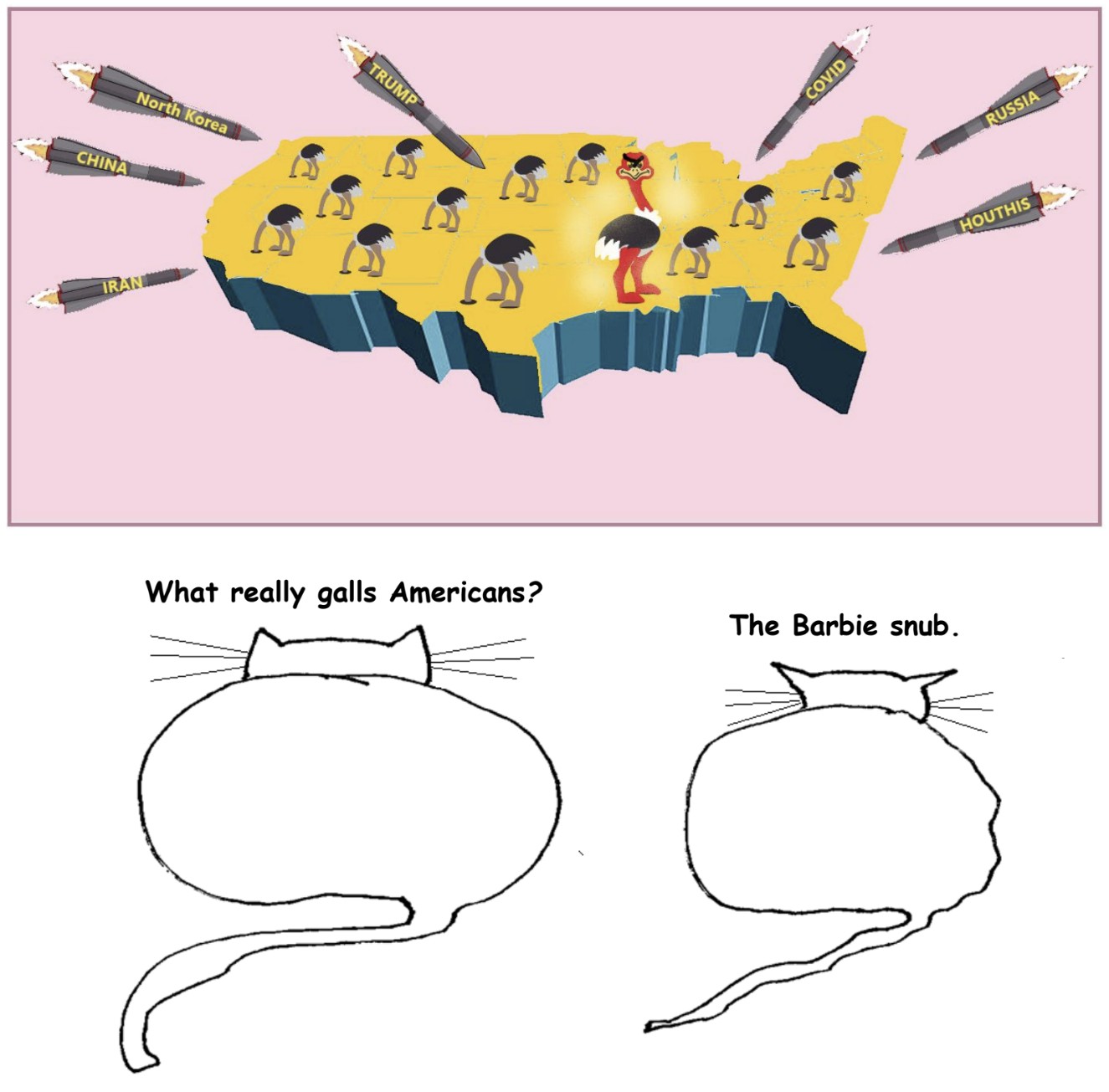

In September 2022, Fiona Hill claimed that with the war in Ukraine, World War III had begun. The statements of the American expert on Russia were clear: World War I and World War II should not be regarded as static and singular moments in history. Even though they were separated by a peaceful period, the latter is part of a whole process leading from one World War to the next. The peaceful period following the Cold War would then be comparable to the interwar period in the 1920’s and the 1930’s. From Hill’s processual point of view peaceful periods are as much part of major conflicts as the actual war periods themselves: from the Cold War via a peaceful period to WW III.

In September 2022, Fiona Hill claimed that with the war in Ukraine, World War III had begun. The statements of the American expert on Russia were clear: World War I and World War II should not be regarded as static and singular moments in history. Even though they were separated by a peaceful period, the latter is part of a whole process leading from one World War to the next. The peaceful period following the Cold War would then be comparable to the interwar period in the 1920’s and the 1930’s. From Hill’s processual point of view peaceful periods are as much part of major conflicts as the actual war periods themselves: from the Cold War via a peaceful period to WW III. As an émigré from the dusty, sun-scorched Carthaginian provinces, there are innumerable sites and experiences in Milan that could have impressed themselves upon the young Augustine – the regal marble columned facade of the Colone di San Lorenzo or the handsome red-brick of the Basilica of San Simpliciano – yet in Confessions, the fourth-century theologian makes much of an unlikely moment in which he witnesses his mentor Ambrose reading silently, without moving his lips. Author of Confessions and City of God, father of the doctrines of predestination and original sin, and arguably the second most important figure in Latin Christianity after Christ himself, Augustine nonetheless was flummoxed by what was apparently an impressive act. “When Ambrose read, his eyes ran over the columns of writing and his heart searched out for meaning, but his voice and his tongue were at rest,” remembered Augustine. “I have seen him reading silently, never in fact otherwise.”

As an émigré from the dusty, sun-scorched Carthaginian provinces, there are innumerable sites and experiences in Milan that could have impressed themselves upon the young Augustine – the regal marble columned facade of the Colone di San Lorenzo or the handsome red-brick of the Basilica of San Simpliciano – yet in Confessions, the fourth-century theologian makes much of an unlikely moment in which he witnesses his mentor Ambrose reading silently, without moving his lips. Author of Confessions and City of God, father of the doctrines of predestination and original sin, and arguably the second most important figure in Latin Christianity after Christ himself, Augustine nonetheless was flummoxed by what was apparently an impressive act. “When Ambrose read, his eyes ran over the columns of writing and his heart searched out for meaning, but his voice and his tongue were at rest,” remembered Augustine. “I have seen him reading silently, never in fact otherwise.”