by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

I was nineteen when I first saw Venice. My college boyfriend and I had taken an overnight train from Vienna and arrived in the mist of early morning. It was late summer. This was at the tail end of almost three months in India, where I saw my fill of glorious wonders. Still, nothing could have prepared me for my first glimpse of the fabled city. First of all, I hadn’t expected the Grand Canal to be right outside the train station. Boarding a vaporetto, I sat speechless. The canal was shimmering like a vision from a dream. Church bells could be heard just above the loud din of the boats, and everywhere I looked: marble palaces stood crumbling into the water. I vividly remember my heart racing as I looked around, not believing the place was real.

“A wonder of the world,” my boyfriend called it on the train from Vienna.

And when I at last found my voice, I asked, “Why does anyone live anywhere else?”

He just laughed.

That was in 1990.

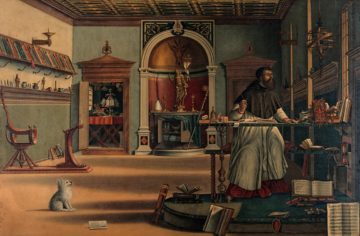

Then as now, traveling to Venice meant being able to view the work of the dazzling trio of Venetian artists that Henry James claimed would “form part of your life in Venice.” Giovanni Bellini and Tintoretto, as well as the great Carpaccio, said James “shall illuminate your view of the universe.” James was hinting at the way that these painters’ works exert an overwhelming power, not only over the way we see Venice, but over our vision of the world. And this is especially true when the great pictures are viewed in situ, in the palaces and churches for which they were originally created. Read more »

The Fate of the Animals: On Horses, the Apocalypse, and Painting as Prophesy (Three Paintings Trilogy), by Morgan Meis, Slant

The Fate of the Animals: On Horses, the Apocalypse, and Painting as Prophesy (Three Paintings Trilogy), by Morgan Meis, Slant