by Akim Reinhardt

Last week marked the 20th anniversary to the start of America’s recently concluded second Gulf War. It’s also been nearly 33 years since the much shorter first Gulf War, a.k.a. Desert Storm (1990–91). Unlike the “great” wars, these haven’t merited Roman numerals.

My own Roman numerals now begin with an L. I am oldish. One of the advantages is that I can conjure fairly clear, adult memories of things that happened quite a while ago. Not just the fragmented, highly impressionistic snapshots leftover from childhood, but recollections of complex interactions and evolving ideas. As a professional historian, I know that some healthy skepticism is called for; such memories are not always reliable and cry out for corroboration. However, as we look back on the Gulf Wars, I’m not interested in reciting history so much as thinking about what they have meant to me. Me: a lifelong American who has never been in the military, but has friends who served in both Gulf Wars, some of whom still struggle with it; me as someone who felt mildly conflicted about the first Gulf War and opposed it meekly, but who spoke out more stridently against the second one.

I was 22 years old when George Bush the elder cast his thousand points of light over Baghdad. I used that war as an excuse not to dodge the draft (there was none), but to dodge work. When the bombs began falling, I called the hospital where I clerked the midnight shift hanging x-rays on alternators, and told them I was taking a personal day, or rather a night, to stay home and watch the news; I had family in Israel, against whom Saddam Hussein was launching batteries of SCUD missiles. It was barely the truth. I do have some very distant family in Israel, but they migrated there from Poland a century ago, I’ve never communicated with any of them, and know nothing of them other than the surname they share with my mother’s family. I used them as an excuse to stay home and watch television, like most Americans.

The first invasion of Iraq was the first ever made-for-TV version of a war. If Vietnam had chaotically and viscerally come flooding into America’s living rooms during the 1960s and 1970s, the first Gulf War was presented as a tightly scripted affair, meant to be rousing and impressive, but ultimately sterile and repetitive. The Pentagon had learned its lesson. No longer would public opinion be swayed against one of its overseas invasions by unruly journalists sending back pictures and footage of American GIs getting chewed up and shot to hell halfway around he the world. Now generals would calmly brag about U.S. military might as they pointed to maps and described blurry, black and white explosions targeting unseen enemies. Approved footage was allocated to TV networks, and the free roaming and mischievous journalists of an earlier generation were escorted about in military-led pools. Supposedly it was for their own safety and national security; even then it felt like the military controlling the messaging and propagandizing the war. And propaganda there was.

Old Man Bush claimed the war was about: 1) stopping unchecked aggression, and; 2) defending democracy. The former argument made some sense as Iraq had invaded its neighbor, Kuwait. The latter claim was utterly laughable as Kuwait was a monarchy. We were literally defending monarchy, not democracy. And the reason was obvious: oil. The messaging worked though. At war’s end, Bush’s approval ratings neared 90%. Which is how we ended up with Bill Clinton, but that’s another story for another time.

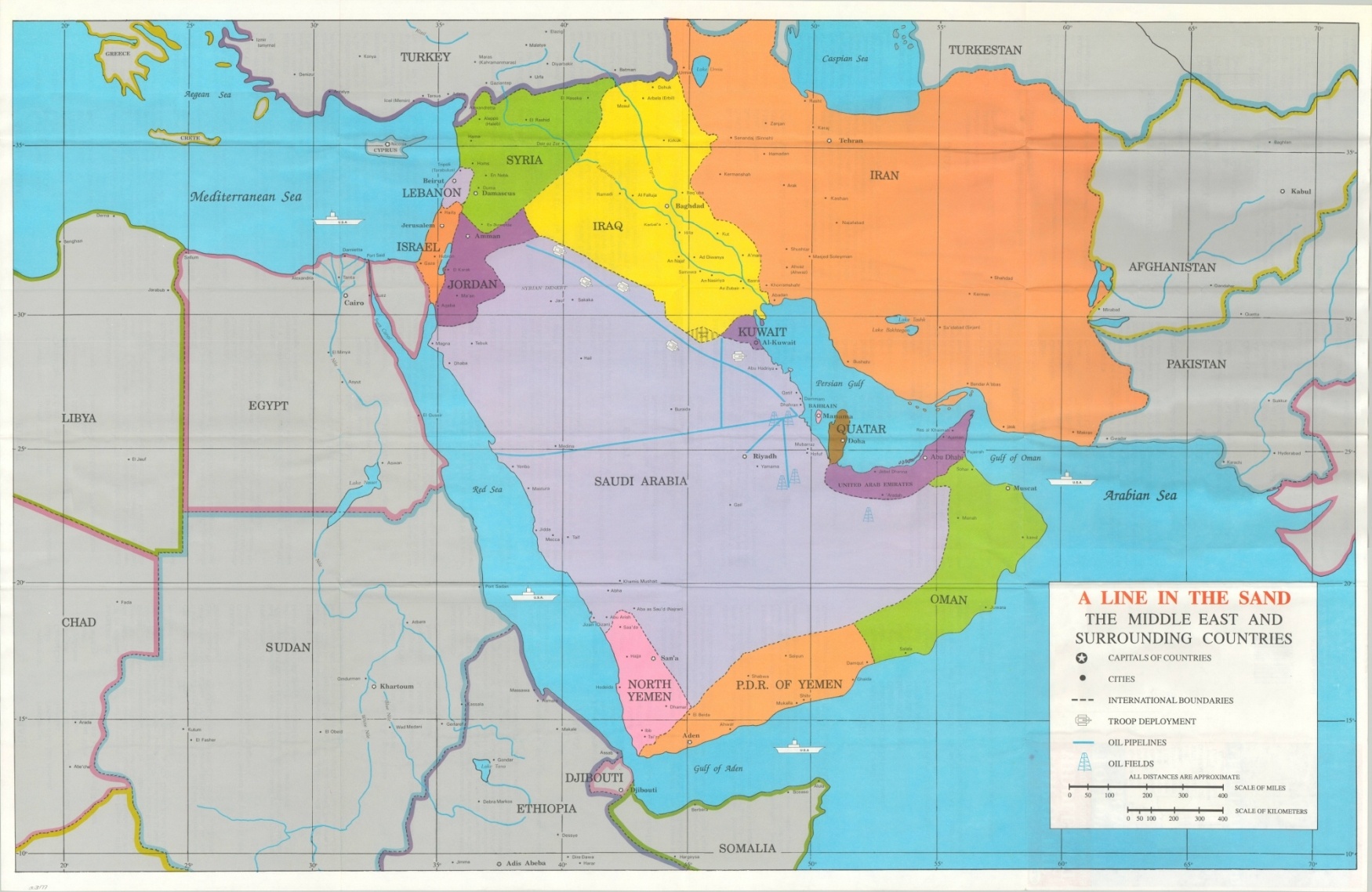

Back in 1990 and 1991, the whole thing felt unwarranted to me, but not a war crime. Hussein was in fact a miserable, authoritarian despot, and his invasion of Kuwait was unjustified. He rallied his people around irredentism: the tiny Gulf nation to their south had historically been part of Persia and was only independent because British imperialists drew a line in the sand decades earlier. This of course was true and a very fair indictment of British imperialism. However, the real reason he’d launched the invasion was not noble decolonialism. It wanted to prop up his own dictatorial regime by canceling a huge debt owed to Kuwait, and by capturing its massive oil reserves. There were also legitimate concerns he might invade Saudi Arabia next and claim half of the world’s oil.

Back in 1990 and 1991, the whole thing felt unwarranted to me, but not a war crime. Hussein was in fact a miserable, authoritarian despot, and his invasion of Kuwait was unjustified. He rallied his people around irredentism: the tiny Gulf nation to their south had historically been part of Persia and was only independent because British imperialists drew a line in the sand decades earlier. This of course was true and a very fair indictment of British imperialism. However, the real reason he’d launched the invasion was not noble decolonialism. It wanted to prop up his own dictatorial regime by canceling a huge debt owed to Kuwait, and by capturing its massive oil reserves. There were also legitimate concerns he might invade Saudi Arabia next and claim half of the world’s oil.

Living in Michigan at the time, I attended a protest but didn’t march in it. I was a deeply cynical young man. I thought the war was bullshit, but the protestors also rubbed the wrong way. Technically, their protest message was largely correct. The war was in fact about blood for oil, not democracy or freedom. It was about the United States maintaining its dominant economic position in the world, effectively overseeing the oil-rich Middle East, and asserting its new lone superpower status as the Cold War unraveled. But I was also jaded enough to wonder which of the hypocritical protestors had shown up in status-driven gas guzzlers. Hippies in VW vans; soccer moms (was that a term yet?) in massive minivans; suburban dads in 4x4s, as SUVs were still called. Fuck them, I didn’t even own a car despite living in the frigid, sprawling Midwest. I wasn’t the problem.

So I opposed the war, but mostly kept it to myself. As we all know, it ended rather quickly with a decisive U.S. victory. And not only did we allow Kuwait to keep its monarchy, we even let Saddam Hussein remain in power. Because unlike his imbecilic son, WWII veteran and former CIA Director George H.W. Bush understood that regime change was a very big bite, perhaps more than most Americans wanted to chew, especially in the Middle East.

Now I look back and wish I’d been less cynical. My cynicism did allow me to recognize that the U.S. casus belli was laughable nonsense, but it also prevented me from sufficiently empathizing with the Iraqi people, who did not deserve to have their nation invaded, and who did deserve better than Saddam Hussein but didn’t receive it. Not for a while, anyway.

When 9-11 exploded a decade later, I was in my early thirties and had just moved to Baltimore to begin my career as a college professor. As a native New Yorker with most of my family still living in and around the city, I was deeply affected. The first time I saw the towers fall, I was certain my cousin, who worked just a few blocks away, must be dead; fortunately she survived. Like most Americans, I felt the United States had to do something. Back in 1990, President Bush had famously asserted “This aggression will not stand.” Now that actually felt like a true and needed statement.

But here’s the thing. I was no longer cynical. I was now thoughtfully critical. U.S. officials kept telling us that September 11th was the work of non-state actors: Al-Qaeda. So if we were going to invade a country, it should be the one that was harboring and supporting Al-Qaeda, right? And based on everything being made publicly available, that nation was Afghanistan, not Iraq.

Al-Qaeda had been founded in 1988 at the tail end of the Soviet war in Afghanistan. Initially it even had tacit U.S. support while fighting the Ruskies. Furthermore, none of the group’s founders had been Iraqi. Its leader, Osama bin Laden, as well as nearly all of the 9-11 bombers, were Saudi Arabian, not Iraqi or Afghani. And Saddam Hussein didn’t even like Al-Qaeda, seeing the organization as a potential threat to his own rule. Nor did they like him, the somewhat secular leader of a mostly Shi’ite nation (Al Qaeda was built on Sunni fundamentalism).

So why the fuck, exactly, were we invading Iraq?

Afghanistan made some sense. It was in fact where Al-Qaeda was based and supported by a Taliban regime that was (and is) truly a horrific, extremist theocracy of the worst sort. No wonder we began bombing the place less than a month after 9-11.

But Iraq? That didn’t make any sense. And lots of Americans, even amid the bloodlust that understandably followed September 11th, at first also didn’t see much reason to invade Iraq. Again.

Yet the junior league Bush regime kept pushing the possibility. Kept the option alive. Kept trying to bring Americans along. And finally trotted out their phony baloney hooey about Weapons of Mass Destruction.

United Nations weapons inspectors had been visiting Iraq for years, making sure it had no nuclear weapon capabilities. But now Bush the Dumber painted the inspectors as mere dupes who’d been sent on wild goose chases by the savvy Saddam. Bush cited a CIA report claiming Hussein had tried to purchase yellow cake uranium from Niger.

Seriously. Niger.

Seriously. Niger.

Surprise surprise, the document, was a forgery. It had been cooked up by U.S. stooges in the Italian intelligence agency SISMI.

I also remember some gibberish about aluminum tubes and mushroom clouds. Secretary of State Colin Powell, high school classmate of my uncle in the Bronx and ever the good soldier, put aside his own doubts, dutifully went to the United Nations, and spouted his boss’ bullshit in a globally televised speech. A couple of years later, Bush replaced him with current Denver Broncos minority owner Condoleeza Rice.

It was all so ludicrous that many of our own allies refused to play along. France declined to join the invading coalition and threatened a UN Security Council veto. In a harbinger of their childishness to come, House Republicans changed their cafeteria menu from French Fries to Freedom Fries.

Indeed, it quickly turned out to be such rancid garbage that the CIA never recovered; in addition to suffering a massive drop in prestige, it permanently lost its power to oversee and coordinate America’s spy agencies; an entirely new entity (Office of the Director National Intelligence) was created to that. And in Italy, SISMI was so discredited that it doesn’t even exist anymore; in 2007 it was replaced with a new agency.

Okay. Some of that I had to look up to verify. But here’s what I remember very clearly.

None of it smelled right to me. I didn’t believe there were WMDs in Iraq. Not for a minute. I thought Bush and his cabinet members were lying through their teeth. Several years after the second Iraq invasion, I even co-authored a piece with sociologist Heather Gautney, first in the French journal La Pensée and eventually in the American journal Peace and Change, trying to sort out why the fuck Bush even invaded Iraq. We considered everything from Foucauldian biopower to some kind of Oedipal complex. I still don’t totally understand it, to be honest.

And those dirty motherfuckers, those rotten sonsabitches in the “liberal lamestream media,” like the New York Times and the New Republic. Yeah, liberal, as in liberal interventionists of the imperial Wilsonian tradition. They loudly supported the invasion. Rah! Rah! Rah! So phenomenally stupid, so shameful, and ultimately embarrassing, that they had to issue retractions years later. Oops-a-daisy! We wuz wrong, so sowwwy.

Did you know that during the runup to the war, MSNBC actually fired host Phil Donahue for being too liberal and speaking out against the proposed invasion?

The Bush regime’s propaganda, facilitated and echoed by mainstream media on both the right and the “left,” was so effective that a majority of Americans came away believing the lie that Iraq gave substantial support to Al-Qaeda and was directly involved in the September 11th attacks. Nearly 70% believed Saddam Hussein had been personally involved in planning 9-11. And nearly a quarter of Americans were so deluded that they magically believed we actually found weapons of mass destruction Iraq. Of course 80% of Fox News viewers believed at least one of these lies. But so did 71% of CBS viewers.

There is a lot of blood on a lot of people’s hands.

But there was a moment: in between the lies being spouted, and the cold, hard proof that revealed them as such. That time from shortly before the invasion until a year or two afterwards, when we couldn’t say for certain that there were no WMDs. After all, it’s often very difficult to prove a negative.

During that period, I debated the issue with my father. A non-voting Rockefeller Republican during my youth (pro-civil rights, pro-slashing taxes, against the death penalty), he’d since become enmeshed in right wing, AM talk radio. Before the internet, that really was the worst of the worst. In some ways it still is. And sure enough, dad bought into the bullshit. He was convinced Saddam had WMDs buried in the sand somewhere, and that we had to go in there and find them.

After talking back and forth, I proposed a long range agreement between us. If WMDs were found, I’d admit I’d been wrong to oppose the invasion, that it was the right thing to do, because Saddam Hussein + nuclear weapons = nightmare. But if they couldn’t find any WMDs, he’d admit he’d been wrong and that the invasion was a mistake. We shook on it.

I hesitate to say my father was a man of his word. He was an alcoholic, and he lied a lot; but mostly about his drinking and things related to it. Yet despite his long history of denials and omissions, he definitely had a strong sense of honor and believed his word meant something. Quite a lot, actually. So a few years later, when it was plumb obvious there weren’t any WMDs in Iraq, I called him on it. Not to rub it in. I had been entirely prepared to admit my error if they’d found WMDs. But of course they hadn’t. And they never have, because they weren’t any. I wanted him to admit, as he said he would do, that the invasion had been a mistake. No I told you so. Just a settling on the truth.

Yeah, he admitted, it looks like there aren’t any WMDs. But then he drew a line. Despite that, he said, the invasion had not been a mistake.

I was stunned. What?

Alas, he had moved on to a new Rush Limbaugh-fed talking poin: the reason we gave for invading Iraq was wrong, but the invasion itself was still a good thing because we were now going to remake the Middle East in a positive way. I think the metaphor was something about having a boot in the region.

I learned something very important that day. Not about either of the Gulf Wars, but about how propaganda works. The truth is a moving target. This was in pre-Trump America, when political lies were already quite frequent, as they had always had been, but larger “truths” were still tied, at least somewhat, to facts, instead of being completely untethered from reality as they are now. Nowadays, the clocks really do strike thirteen. Back then, bullshit could occasionally be countered by shame.

Now we are shameless, and all we have left are the lies.

The second invasion of Iraq (2003–2011), born of mendacity, was a disaster in many ways for countless people. Perhaps the invasion and occupation of Afghanistan, which finally concluded in 2020, was the right thing. But the Taliban’s back in power regardless. Old Man Bush was right about regime change. It’s a bear.

I’m not bragging by pointing out that I did what little I could (very little, actually) to try and prevent it the second Iraq invasion. Rather, I’m mourning that it happened. And I’m saddened that making it happen required pulling several more bricks from the dike, as we now find our democracy drowning in a flood of lies, conspiracies, and excuses, awash in a sea of delusion.

I’m not bragging by pointing out that I did what little I could (very little, actually) to try and prevent it the second Iraq invasion. Rather, I’m mourning that it happened. And I’m saddened that making it happen required pulling several more bricks from the dike, as we now find our democracy drowning in a flood of lies, conspiracies, and excuses, awash in a sea of delusion.

Maybe it was only ever a dream. But now I am awake. And as I raise my head to look about, I know that what I wanted was never real and might never be.

Akim Reinhardt’s personal pack of lies website is ThePublicProfessor.com