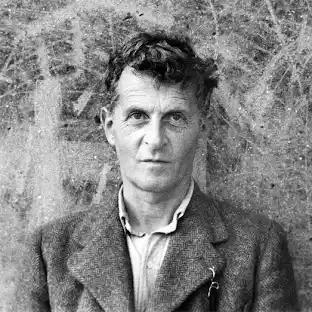

by Katalin Balog

If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, Infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro’ narrow chinks of his cavern. —William Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell

Laments about young people’s declining mental health, their inability to read novels, contemplate art, or simply pay undivided attention to anything at all have reached a panicky intensity lately. Not being particularly young, I can distinctly remember a time when things were less dire in this regard (except for the mental health part, having grown up in Eastern Europe…). We loved the films of Antonioni, Bergman, Tarkovsky, and Tarr, whose slow pace, for the most part, would be out of the question in today’s film industry. We were able to entertain ourselves without being entertained.

I propose that there is a common thread to these problems, and of course, they don’t only afflict the kids. We are all losing our ability to engage in a way of thinking I call contemplation. Young people are in an especially difficult place: whereas older people still remember and possess that ability to some degree, younger people have not had much opportunity to pick it up in the first place. And while it always required a certain amount of leisure and cultivation, a certain amount of groundedness and prosperity, today, contemplation is widely underappreciated and is in decline.

Contemplation is more than simply having experience; not all experiencing counts as contemplation – otherwise, we would all be automatically non-stop contemplators! In contemplation, experience is “held” in attention and explored without a particular goal in mind. This is different from other forms of attention deployed in thought or perception, which are fast-moving and task-oriented. Contemplation happens in small ways every time we stop to appreciate the world as we experience it, every time we are present for what is happening in a deliberate fashion, rather than breezing through in automatic pilot (or being absorbed in thought to the exclusion of experience). This could be a momentary lingering on someone’s body language or the way they express themselves. It could be an experience of merging with the natural environment. It could be a state of reflection reading a novel or poem. It could be just sitting and mulling over some experience of the day. Thomas Nagel said that there is “something it’s like” to have an experience. Contemplation then is attention to what it’s like. Read more »

Julya Hajnoczky. Boletinellus Merulioides

Julya Hajnoczky. Boletinellus Merulioides Maybe it’s defeat in a short, sharp war far from home. Maybe Russia captures Ukraine, or China attacks Taiwan. Maybe nothing happens yet, maybe it’s four or eight years away, but however the big change comes we’ll all agree the signs were there all along.

Maybe it’s defeat in a short, sharp war far from home. Maybe Russia captures Ukraine, or China attacks Taiwan. Maybe nothing happens yet, maybe it’s four or eight years away, but however the big change comes we’ll all agree the signs were there all along.

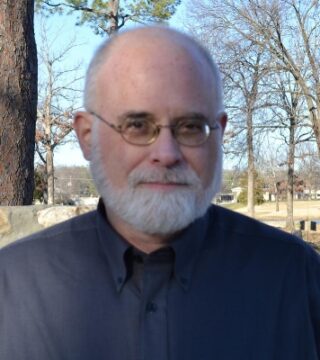

For over twenty years I have been in awe of David Jauss as a writer, as a colleague and teacher, and above all for his insight into the contradictory human heart. His short stories have been gathered together in two essential collections,

For over twenty years I have been in awe of David Jauss as a writer, as a colleague and teacher, and above all for his insight into the contradictory human heart. His short stories have been gathered together in two essential collections,

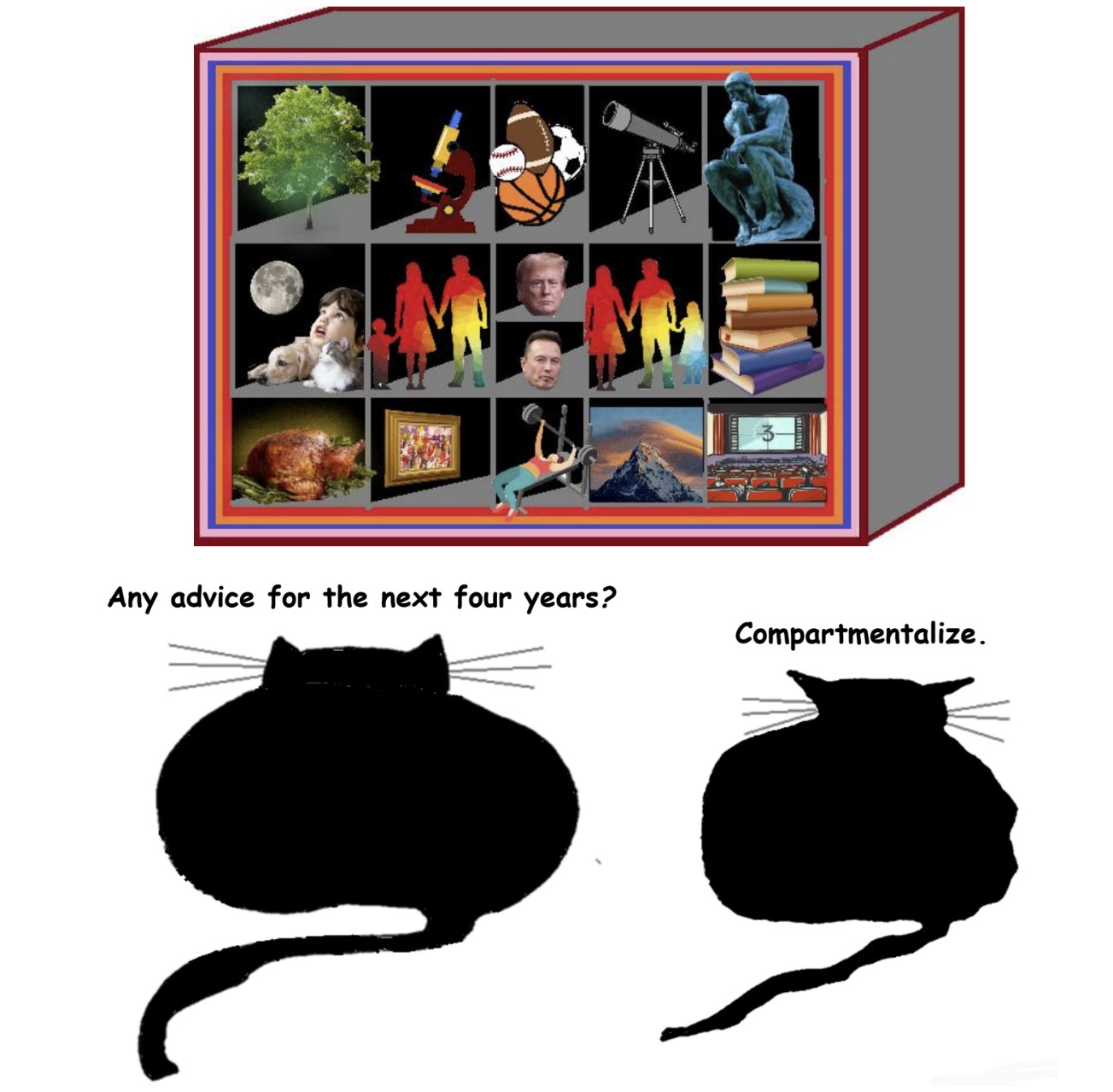

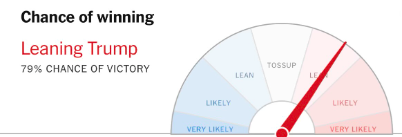

On November 5, 2024, at around 10:30 pm, I walked into a bar, approached the counter, and sat down on the stool second from the right. I ordered a stout because there was a slight chill in the air. As this was the night of the American presidential election, I pulled out my phone and checked The New York Times website, which said Donald Trump had an 80% chance of winning. This was my first update on the election, and it seemed bad. I put my phone back in my pocket and took a sip of the stout. A man entered the bar and sat down next to me, on my right. There was a half-drunk glass there, and I realized he’d gone out to smoke but had probably been at the bar for a while. Besides us—two solitary men at the bar—the rest of the place was busy, full of couples and groups who seemed to be unconcerned with the election. This may have been because I was in Canada, but my experience of living in Canada for the past four years has shown me that Canadians are just as interested in American politics as Americans are, if not more so. My work colleagues had been informing me of the key swing states, for example, while I had simply mailed in my meaningless Vermont vote and returned to my life. I had no idea who would win this election.

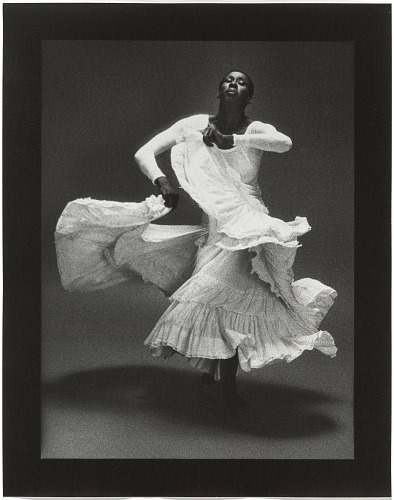

On November 5, 2024, at around 10:30 pm, I walked into a bar, approached the counter, and sat down on the stool second from the right. I ordered a stout because there was a slight chill in the air. As this was the night of the American presidential election, I pulled out my phone and checked The New York Times website, which said Donald Trump had an 80% chance of winning. This was my first update on the election, and it seemed bad. I put my phone back in my pocket and took a sip of the stout. A man entered the bar and sat down next to me, on my right. There was a half-drunk glass there, and I realized he’d gone out to smoke but had probably been at the bar for a while. Besides us—two solitary men at the bar—the rest of the place was busy, full of couples and groups who seemed to be unconcerned with the election. This may have been because I was in Canada, but my experience of living in Canada for the past four years has shown me that Canadians are just as interested in American politics as Americans are, if not more so. My work colleagues had been informing me of the key swing states, for example, while I had simply mailed in my meaningless Vermont vote and returned to my life. I had no idea who would win this election. Max Waldman. Judith Jamison in “Cry”, 1976.

Max Waldman. Judith Jamison in “Cry”, 1976.

What does the election of Trump mean for risks to society from advanced AI? Given the wide spectrum of risks from advanced AI, the answer will depend very much on which AI risks one is most concerned about.

What does the election of Trump mean for risks to society from advanced AI? Given the wide spectrum of risks from advanced AI, the answer will depend very much on which AI risks one is most concerned about.