by Martin Butler

Fewer than half the population in the UK believe in God according to the latest surveys, even though religious belief is growing globally and the heady days when the ‘new atheists’ were in full flight are now behind us. The internet has given those on opposite sides of the fence the opportunity to lock horns continually, each side determined to show the irrationality if not downright stupidity of their opponents. I wouldn’t expect the level of debate to be particularly high, but what I do find slightly depressing is the complete absence of anything but the crudest understanding of what belief in God and religious belief in general actually means. Both sides mostly embrace the ‘God of the gaps’ theory – science cannot explain everything, runs the argument, and God serves as a kind of backstop to account for the unexplained.

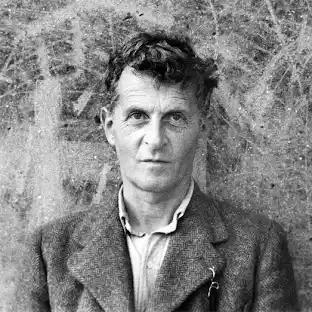

Ludwig Wittgenstein, one of the most important philosophers of the 20th century can, I think, help us to develop a more sophisticated conception of religious belief.[1] Despite never producing anything close to a philosophy of religion, the religious point of view was clearly important to him throughout his life: ‘I am not a religious man but I can’t help but seeing every problem from a religious point of view’ (RW p79). Although, Elizabeth Anscombe, a devout Catholic and one of his most famous pupils, once declared that ‘nobody understood Wittgenstein’s views on religion.’[2]

Wittgenstein famously produced two quite distinct approaches to philosophy, the first in the only book he published in his lifetime, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, and the second in the Philosophical Investigations, published posthumously; although there have been many other publications over the years of his extensive notebooks and conversations. Towards the end of the Tractatus several important remarks set the stage for his approach to religious belief through both periods of his philosophy. ‘We feel,’ he says, ‘that even when all possible scientific questions have been answered, the problems of life remain untouched’ (TLP 6.52).

It is with these ‘Lebensprobelme’, which cannot be ‘solved’ through science, that religious belief is concerned. The problems of life cannot be stated as genuine questions since if they could, factual answers describable by science could be given: ‘If a question can be framed at all, it is also possible to answer it’ (TLP 6.5), whereas the problems of life are concerned with what cannot be said – what he refers to elsewhere as the mystical. Read more »

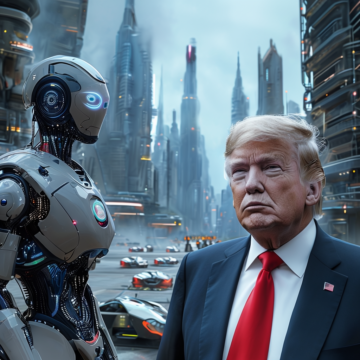

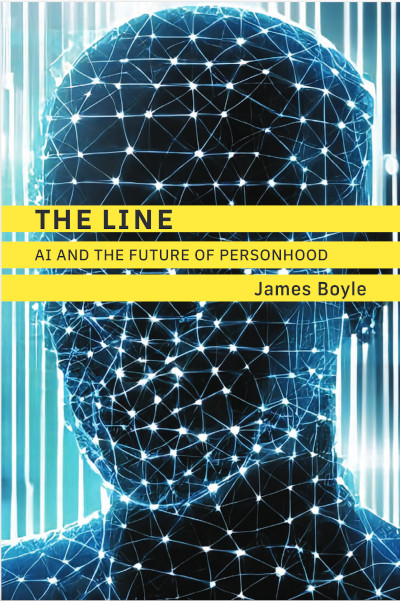

What does the election of Trump mean for risks to society from advanced AI? Given the wide spectrum of risks from advanced AI, the answer will depend very much on which AI risks one is most concerned about.

What does the election of Trump mean for risks to society from advanced AI? Given the wide spectrum of risks from advanced AI, the answer will depend very much on which AI risks one is most concerned about.

I dipped my toe into

I dipped my toe into  Professor Paul Heyne practiced what he preached.

Professor Paul Heyne practiced what he preached.

by William Benzon

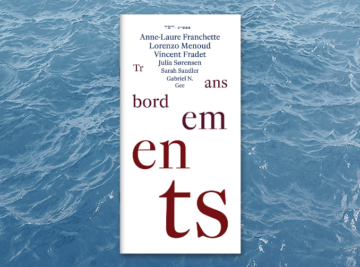

by William Benzon Last Saturday, November 2, 2024, at a collective atelier in Zurich’s Wiedikon neighborhood, I attended the launch of a new periodical.

Last Saturday, November 2, 2024, at a collective atelier in Zurich’s Wiedikon neighborhood, I attended the launch of a new periodical.

In 1919, Otto Neurath was on trial for high treason, for his role in the short-lived Munich soviet republic. One of the witnesses for the defense was the famous scholar Max Weber.

In 1919, Otto Neurath was on trial for high treason, for his role in the short-lived Munich soviet republic. One of the witnesses for the defense was the famous scholar Max Weber.

Historians have spilled much ink analyzing and interpreting all of the U.S. presidential elections, dating back to George Washington’s first go in 1788. But a handful of contests get more attention than others. Some elections, besides being important for all the usual reasons, also provide insights into their eras’ zeitgeist, and proved to be tremendously influential far beyond the four years they were intended to frame.

Historians have spilled much ink analyzing and interpreting all of the U.S. presidential elections, dating back to George Washington’s first go in 1788. But a handful of contests get more attention than others. Some elections, besides being important for all the usual reasons, also provide insights into their eras’ zeitgeist, and proved to be tremendously influential far beyond the four years they were intended to frame.

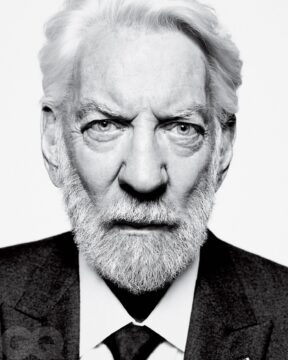

Donald Sutherland was a connoisseur of poetry. In the 80s I knew poetry-quoting doyennes from the glittering parties the Academy of American Poets threw as well as the Sudanese who recited their histories in song, but mostly I knew poets obsessed with competing with dead ones, with an eye toward their next book. Poets generally love poetry the way auto mechanics love cars. They don’t luxuriate in the front seat, or take long winding car trips through the Berkshires, they make sure the ignition catches and go on to the next one. Hearing Sutherland recite poetry you heard the Stanislavski method of poetry-recitation, an oral delivery straight from the mind as well as the mouth. Sutherland said he was manipulated by words, not as a ventriloquist but in the relationship between feeling and meaning. Likewise, after numerous tussles with directors Fellini and Preminger and Bertolucci – he even tried to get Robert Altman fired from M.A.S.H. – he decided he was merely the director’s vehicle. Poetry directed him.

Donald Sutherland was a connoisseur of poetry. In the 80s I knew poetry-quoting doyennes from the glittering parties the Academy of American Poets threw as well as the Sudanese who recited their histories in song, but mostly I knew poets obsessed with competing with dead ones, with an eye toward their next book. Poets generally love poetry the way auto mechanics love cars. They don’t luxuriate in the front seat, or take long winding car trips through the Berkshires, they make sure the ignition catches and go on to the next one. Hearing Sutherland recite poetry you heard the Stanislavski method of poetry-recitation, an oral delivery straight from the mind as well as the mouth. Sutherland said he was manipulated by words, not as a ventriloquist but in the relationship between feeling and meaning. Likewise, after numerous tussles with directors Fellini and Preminger and Bertolucci – he even tried to get Robert Altman fired from M.A.S.H. – he decided he was merely the director’s vehicle. Poetry directed him.