by Nils Peterson

There’s that list of religions from which we’re offered a choice. If none of them quite fit, at the bottom there’s None. Well that’s not for me either so I’ve taken to calling myself a Non-None. My religious feeling is not defined by any of the above, but it certainly is not defined by None. Some thoughts.

While knotting my shoes, which gets harder as I get older, I realized that if I were Catholic I would prefer to go to a church, well, cathedral really, in which the mass was sung in Latin. I’ve sung many of the great mass settings which are in Latin, and I know enough Latin to understand what I’m singing and conductors always insist on singers having a sense of what the sounds coming out of their mouths mean, but while tying my shoes I realized that I didn’t care about understanding. What I wanted was the incantatory sound, the glorious AH of Ave, the dark EH of Requiem, the round OH of Gloria. It was the sound that penetrated me, of what has sometimes been called “the holy vowels,” – think of the OM sound that some feel is the heartbeat of the universe. How rich it is to say, richer even in a chant. Some would say, and I for the moment agree, it is an all-encompassing sound. So maybe understanding the words of the mass gets in the way of the mass. I don’t insist on this, but wonder.

Remember the ending of Hopkins’ “God’s Grandeur?”

And for all this, nature is never spent;

There lives the dearest freshness deep down things;

And though the last lights off the black West went

Oh, morning, at the brown brink eastward, springs —

Because the Holy Ghost over the bent

World broods with warm breast and with ah! bright wings.

How great that ah! is. It is an Ah of Awe, and we feel the awe deep down, and the exhalation of our saying is prayer. (I admit that it’s good to understand the words of Hopkins that bring us to that great sound then releases us from it.)

I think we have lost the feeling of awe and so the universe we live in has grown smaller except for the astrophysicists who seem to understand the universe as a vast cathedral. Once here on earth we found the language of awe. That language was the cathedral. It spoke our feeling of awe and also recreated it in us. (Yes, there are smaller spaces that offer their version of that experience and if we use eyes and ears, nature too enjoys building cathedrals. Maybe there’s nothing that’s not.) Read more »

In daily life we get along okay without what we call thinking. Indeed, most of the time we do our daily round without anything coming to our conscious mind – muscle memory and routines get us through the morning rituals of washing and making coffee. And when we do need to bring something to mind, to think about it, it’s often not felt to cause a lot of friction: where did I put my glasses? When does the train leave? and so on.

In daily life we get along okay without what we call thinking. Indeed, most of the time we do our daily round without anything coming to our conscious mind – muscle memory and routines get us through the morning rituals of washing and making coffee. And when we do need to bring something to mind, to think about it, it’s often not felt to cause a lot of friction: where did I put my glasses? When does the train leave? and so on. A good poem can do many things – be clever, edifying, provocative, or moving – but a truly great poem (which is to say a successful one), need only be concerned with one additional attribute, and that is an arresting turn of phrase. By that criterion, Ukrainian-American poet Ilya Kaminsky’s “We Lived Happily During the War,” originally published in Poetry in 2013 and later appearing in the 2019 collection Deaf Republic, is among the greatest English-language verses of this abbreviated century. Within the context of Deaf Republic, Kaminsky’s lyric takes part in a larger allegorical narrative, but that broader story in the collection aside, “We Lived Happily During the War” is arrestingly prescient of both the 2014 Russian invasion of Crimea and Vladimir Putin’s brutal and ongoing assault on the broader country of Kaminsky’s birth since 2022, including bombardment of the poet’s home city of Odessa. Yet even stripped of this context, “We Lived Happily During the War” concerns itself with the general tumult of modern warfare, both its horror and prosaicness, its sanitation and its tragedy. More than just about Ukraine, or Syria, or Gaza, Kaminsky’s lyric is about us, those comfortable Western observers of warfare who have the privilege to be happy and content at the exact moment that others are being slaughtered.

A good poem can do many things – be clever, edifying, provocative, or moving – but a truly great poem (which is to say a successful one), need only be concerned with one additional attribute, and that is an arresting turn of phrase. By that criterion, Ukrainian-American poet Ilya Kaminsky’s “We Lived Happily During the War,” originally published in Poetry in 2013 and later appearing in the 2019 collection Deaf Republic, is among the greatest English-language verses of this abbreviated century. Within the context of Deaf Republic, Kaminsky’s lyric takes part in a larger allegorical narrative, but that broader story in the collection aside, “We Lived Happily During the War” is arrestingly prescient of both the 2014 Russian invasion of Crimea and Vladimir Putin’s brutal and ongoing assault on the broader country of Kaminsky’s birth since 2022, including bombardment of the poet’s home city of Odessa. Yet even stripped of this context, “We Lived Happily During the War” concerns itself with the general tumult of modern warfare, both its horror and prosaicness, its sanitation and its tragedy. More than just about Ukraine, or Syria, or Gaza, Kaminsky’s lyric is about us, those comfortable Western observers of warfare who have the privilege to be happy and content at the exact moment that others are being slaughtered.

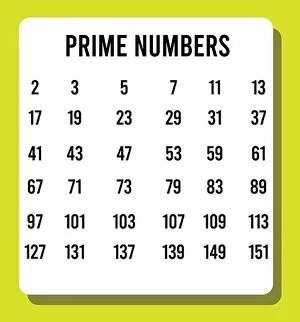

Prime numbers are the atoms of arithmetic. Just as a water molecule can be broken into two hydrogen and one oxygen atoms, 12 can be broken into two 2s and a 3. Indeed, the defining feature of a prime number is that it cannot be factored into a nontrivial product of two smaller numbers. Two primes that are easy to remember are

Prime numbers are the atoms of arithmetic. Just as a water molecule can be broken into two hydrogen and one oxygen atoms, 12 can be broken into two 2s and a 3. Indeed, the defining feature of a prime number is that it cannot be factored into a nontrivial product of two smaller numbers. Two primes that are easy to remember are

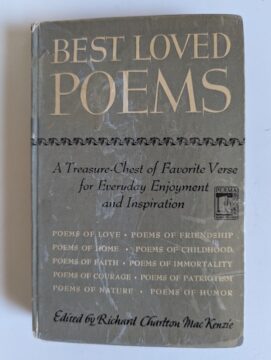

When I was growing up, my mother and I would sometimes read or recite poetry to each other. Ours was not a poetic household, and my father would occasionally complain: “If poets have something to say, why don’t they just say it?” But we thought they did say it, albeit indirectly sometimes, and we continued with our Longfellow, a bit more quietly.

When I was growing up, my mother and I would sometimes read or recite poetry to each other. Ours was not a poetic household, and my father would occasionally complain: “If poets have something to say, why don’t they just say it?” But we thought they did say it, albeit indirectly sometimes, and we continued with our Longfellow, a bit more quietly.