by Sauleha Kamal

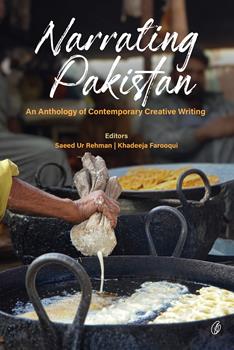

Narrating Pakistan: An Anthology of Contemporary Creative Writing sets a lofty aim for itself: “to explore the idea of Pakistan through contemporary stories—the term, the country, the nation, the identity…”. There have been a few attempts to anthologize Pakistan in the past few decades. Oxford University Press anthologies like I’ll Find My Way (2014), Muneeza Shamsie’s two collections (which the preface to this book mentions), Granta 112: Pakistan (2011) and, as far as academic explorations of Pakistan go, The Routledge Companion to Pakistani Anglophone Writing come to mind. Ultimately, this anthology sets itself apart by telling, not the story of Pakistan but the story of young Pakistan. The characters in these stories are often young people—children, teenagers and young adults—dealing with the trauma of confronting what is, what could have been and what will be. This anthology brings together various writers who write about everything from dreaming of casting off economic shackles—in small villages, giant metropolises and foreign cities that glitter with promise and danger—to confronting isolation—following the Coronavirus pandemic, immigration or a depressive episode. There are stories that explore humanity through the loneliness of the female experience in a patriarchal milieu and the difficulties of conceptualizing Muslim masculinity in post-9/11 America.

Narrating Pakistan: An Anthology of Contemporary Creative Writing sets a lofty aim for itself: “to explore the idea of Pakistan through contemporary stories—the term, the country, the nation, the identity…”. There have been a few attempts to anthologize Pakistan in the past few decades. Oxford University Press anthologies like I’ll Find My Way (2014), Muneeza Shamsie’s two collections (which the preface to this book mentions), Granta 112: Pakistan (2011) and, as far as academic explorations of Pakistan go, The Routledge Companion to Pakistani Anglophone Writing come to mind. Ultimately, this anthology sets itself apart by telling, not the story of Pakistan but the story of young Pakistan. The characters in these stories are often young people—children, teenagers and young adults—dealing with the trauma of confronting what is, what could have been and what will be. This anthology brings together various writers who write about everything from dreaming of casting off economic shackles—in small villages, giant metropolises and foreign cities that glitter with promise and danger—to confronting isolation—following the Coronavirus pandemic, immigration or a depressive episode. There are stories that explore humanity through the loneliness of the female experience in a patriarchal milieu and the difficulties of conceptualizing Muslim masculinity in post-9/11 America.

A story about young Pakistan today cannot be told without telling the story of leaving Pakistan, as more and more young Pakistanis do every year. Many of the stories in this anthology are about the consequences of leaving and the challenges of diasporic existence. Many of these stories deal with the alienation of being a person of color in places that are not too kind to people with the wrong skin color, to paraphrase the wording of multiple stories. The idea of the wrongness of an “epidermis” crops up in both Syed Kazim Ali Kazmi’s “Trans/Gress” and Saeed Ur Rehman’s “The Sharpness of Grass Blades”. The narrator in Aatif Rashid’s “Brown Mirror” yearns to peel off his brown skin.

Rehman’s story, which finds a Pakistani student planning to overstay his Australian visa, perhaps best captures one of the darkest manifestations of yearning to belong elsewhere. This story succeeds because of its masterful balance of light humor (e.g. the narrator’s reference to his roommate’s “hobby of maggot farming in takeaway pizza boxes”) and an unflinching indictment of the global inequalities that restrict the freedoms of people in certain bodies. While it never quite becomes clear what drives the narrator’s desperation to stay away from Pakistan, this is an answer that might complete the story of Pakistan that this anthology tells.

“Nostographia”, Bassam Sidki’s nonfiction meditation on illness and immigration turns the malaise of homesickness into an exploration of what happens when you suffer a serious illness in a new place that is not quite home. The prose in this piece, with its overly formal quirks has a distinctive nineteenth century quality which works well with the history of the clinical diagnosis of nostalgia from the nineteenth century and the after-effects of colonialism threaded through this essay as well as with the author’s memory of the “Pakistani English, a remnant of the British English taught at my old school” alienating him from his American classmates. The final sentence strikes a painful yet beautiful chord: “Longing to go home, dying to go home”. On the subject of illness, Khadeeja Farooqui’s evocatively-titled “Coughing up Glass” transports the reader back to the anxiety of 2020 with its reflections on two subjects people tend to avoid: class and the coronavirus. Laying bare the contradictions exposed in the wake of suspension of normalcy, Farooqui captures a certain segment of Lahori society.

Usama Lali’s “Khicheenk!” and Hananah Zaheer’s “Fish Tank” tell two very different stories of masculinity. Lali’s sublime little tale brings the rural and the urban together. The first paragraph, in its matter-of-fact plain style, recounts the story of an arranged marriage between a young widow and an older widower which was decided with the hope that the two would “be less sad together”. In retrospect, the decision was, to the narrator who is the product of this union, akin to “electrocuting a dead frog and calling its spasming body alive”. The ensuing pages are a masterclass in parsing humanity, the burdens fathers and sons place on each other’s shoulders and the quiet love that endures despite everything. Zaheer’s story, meanwhile, is chilling in its breathless portrayal of the clash between two distinct but cross-cutting spheres: gender and class. Told from the perspective of lower-level employees of the Metro and Waterways Department, the trouble in this story begins when a new manager joins the office. A young American-educated engineer who comes from money and wears red lipstick, this new manager injures the pride of the members of her staff who see it as a personal affront that a younger woman should outrank them and inspire both sexual and economic envy. That the narration is delivered without judgment makes it all the more effective.

In The Program Era (2009), Mark McGurl argues that postwar American writing can only be understood in the context of the rise of the creative writing program, exploring the imprint of the MFA on American letters. This imprint is certainly visible on Pakistani writing in English as well and this anthology is a timely reminder of this phenomenon. There is the feeling that too many narrators in these stories are writers and MFA students, and while the writerly reflections are interesting in their own way, the anthology is at its most exciting when the stories move away from chronicling the Writer Experience. Some of the strongest stories in this collection take the lessons of style, attention-to-detail and tight prose learned in formal writing classes and apply them to new contexts. One example is Aamina Ahmad’s “July Sun”. Set in a village, this story portrays the tragic consequences of disrupting tradition. The hallmark of formal writing rules are visible in this story. Ahmad uses implements from her writer’s toolkit—a simple but striking beginning (“Ghulam Ali pushed his way through the sugarcane”) and an ending where nothing has changed but something clearly has (“it was as if nothing at all had ever happened”)—to paint a picture of the kind of place that is hardly ever written about. Farah Ali’s “Bulletproof Bus” similarly brings to life an everyday tale of misfortune and desperation from the streets of Karachi. Her narrator is an ordinary man who dreams of a better life but struggles to find a job with his impoverished circumstances and limited English. The eponymous bus comes alive with Ali’s dramatization of the narrator’s yearning as he latches onto the hope of becoming its driver. The visceral descriptions in this story have the reader mirroring his hopes and emotions until the perhaps predictable but very effective denouement.

The final story—“Narrating the Cities of Pakistan” by ChatGPT–is a valiant effort by the OpenAI Language Learning Model which took the world by storm in 2023. With some good phrases (like “Islamabad, the fortress of bureaucracy”) but an ultimate lack of discernible plot and structure, this piece underscores the importance of the formal writing program.

Narrating Pakistan is a refreshing anthology that is certainly impressive in its sheer breadth. The stories present a revolving carousel of tales that capture contemporary Pakistan. Despite the tongue-in-cheek nod towards Mohsin Hamid in the preface, the ubiquity of the second-person perspective in this collection suggests his enduring influence. That this anthology contains new stories and reprints creates a minor conundrum. The original stories from this collection present something new and interesting. While the reprints do help complete the puzzle of Pakistan that this anthology puts together, ten reprints out of nineteen stories in total feels like a little too much. That said, this collection is a much-needed one-stop shop for anyone looking to read about young Pakistan today.

***

Sauleha Kamal is a researcher and writer. Her current academic book project looks at the connections between the anglophone Pakistani novel, empathy and human rights and problematizes these connections in terms of the economic aims of the literary marketplace. She is an alumna of the University of Cambridge, where she was a Chevening & Cambridge Trust scholar, and Barnard College, Columbia University, where she studied English and Economics. Her work has appeared in various places including The New Yorker, The Atlantic, Catapult, the Journal of Postcolonial Writing and Postcolonial Text. She is co-editing a special issue for the Journal of World Literature. She was a writer-in-residence at Yaddo in Saratoga Springs, New York in Fall 2019.

Sauleha Kamal is a researcher and writer. Her current academic book project looks at the connections between the anglophone Pakistani novel, empathy and human rights and problematizes these connections in terms of the economic aims of the literary marketplace. She is an alumna of the University of Cambridge, where she was a Chevening & Cambridge Trust scholar, and Barnard College, Columbia University, where she studied English and Economics. Her work has appeared in various places including The New Yorker, The Atlantic, Catapult, the Journal of Postcolonial Writing and Postcolonial Text. She is co-editing a special issue for the Journal of World Literature. She was a writer-in-residence at Yaddo in Saratoga Springs, New York in Fall 2019.