by Ed Simon

I’m haunted by the enormity of all of that which I’ll never read. This need not be a fear related to those things that nobody can ever read, the missing works of Aeschylus and Euripides, the lost poems of Homer; or, those works that were to have been written but which the author neglected to pen, such as Milton’s Arthurian epic. Nor am I even really referring to those titles which I’m expected to have read, but which I doubt I’ll ever get around to flipping through (In Search of Lost Time, Anna Karenina, etc.), and to which my lack of guilt induces more guilt than it does the real thing. No, my anxiety is born from the physical, material, fleshy, thingness of the actual books on my shelves, and my night-stand, and stacked up on the floor of my car’s backseat or wedged next to Trader Joe’s bags and empty pop bottles in my trunk. Like any irredeemable bibliophile, my house is filled with more books than I could ever credibly hope to read before I die (even assuming a relatively long life, which I’m not).

I’m haunted by the enormity of all of that which I’ll never read. This need not be a fear related to those things that nobody can ever read, the missing works of Aeschylus and Euripides, the lost poems of Homer; or, those works that were to have been written but which the author neglected to pen, such as Milton’s Arthurian epic. Nor am I even really referring to those titles which I’m expected to have read, but which I doubt I’ll ever get around to flipping through (In Search of Lost Time, Anna Karenina, etc.), and to which my lack of guilt induces more guilt than it does the real thing. No, my anxiety is born from the physical, material, fleshy, thingness of the actual books on my shelves, and my night-stand, and stacked up on the floor of my car’s backseat or wedged next to Trader Joe’s bags and empty pop bottles in my trunk. Like any irredeemable bibliophile, my house is filled with more books than I could ever credibly hope to read before I die (even assuming a relatively long life, which I’m not).

“A strong and bitter book-sickness floods one’s soul,” writes Nicholas Basbanes in A Gentle Madness: Bibliophiles, Bibliomanes, and the Eternal Passion for Books. “How ignominious to be strapped to this ponderous mass of paper, print, and dead men’s sentiments!” My books sit two levels deep on the de rigueur millennial’s sagging white IKEA BILLY shelves, the planks having lost their dowls while buckling underneath the weight, titles creatively pushed into any absence that they can credibly fill. There are cairns of books on my office floor, megaliths of books along my windowsill, ziggurats of books in the mudroom, the basement, the attic. A whole shelf of Penguin Classics, their zebra-colored spines announcing themselves – Castiglione’s The Book of Courtier, Baudelaire’s Flowers of Evil. Sprinkled throughout the rest are an assortment of Oxford World Classics, Library of America editions, Nortons. There are other classics – The Aeneid, Moby-Dick, et el. There are contemporary works – Portnoy’s Complaint, Slouching Towards Bethlehem. Categories for reference and poetry, academic and journalistic. Then there is the disposable that I’ve held onto (too polite to name names). Naturally, the question posed to me by any visitor who isn’t a bibliophile (though predictably I know few of that sort) is if I’ve read all of these books. My reply, as close to a joke as I can muster about the affliction, is that I’ve at least opened all of them. I think.

All of those unread books (and yes, of course, I’ve read many of the ones I own) seem to wait in judgement, their uncreased spines, pages without dog-ears, sentences free of underlined ink all serving to remind me of the finitude of my own life. Occasionally I anxiously count the piles of new ones from bookstores, libraries, that website named after a tropical rainforest, configuring ever-shifting schedules of the order in which I should read them, which then inevitably comes up against the reality of ever-diminishing time and responsibility. And so, in my more lucid and self-generous moments I assuage myself with the advice that a mentor once gave me, which was that having more books than you could ever read in a lifetime means that you’ll never run out of material, that such richness and ever-dizzying bounty is more impressive than the ever-masculine idiocy that equates tackling books (that verb…) like putting notches on a bed-post (don’t trust people who do that either).

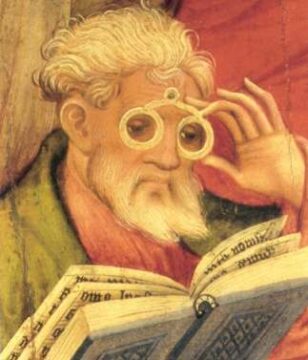

This is the estimably accurate advice of none other than that great empiricist and bibliomaniac Francis Bacon, who in his 1625 Of Studies counselled that “Some books are to be tasted, others to be swallowed, and some few to be chewed and digested; that is, some books are to be read only in parts; others to be read, but not curiously; and some few to be read wholly, and with diligence and attention.” As a credo, I’ve tried my best to live by Bacon’s dictum, which for the most part, when I’m conscious, I think that I’m largely successful with. Bacon has helped me overcome the grad student’s immature preening towards completism, so that as when I was a child enjoying thumbing through Usborne Books or Klutz titles and examining that which struck my attention and wisely disregarding the rest, I can once again take joy in being able to choose. Reading a bit of this, but not that, enjoying some chapters and skimming over others. The only genre that’s allergic to such snacking are novels, which by their very nature are to be “chewed and digested.” The form, because it’s purpose is to insert you into a consciousness, into a world, demands attention. Novels must either be read in their entirety, abandoned, or not even started to begin with. There are no other options.

In that spirit then I offer a menu of that which I’ve chewed and digested in the past year. These are all novels which I read – in their entirety! – during 2023. I haven’t included nonfiction, since that’s the realm in which I normally hold residence anyhow, nor have I mentioned books which I have reviewed elsewhere, seeing little in reiterating the same points. This is, by its necessity, an incomplete list. Because I’ve tried to craft this selection with some intentionality, it doesn’t make sense to include everything, so as a result some books which I enjoyed are not to be found here, especially canonical things that I’ve revisited. As a result, this is a partial Polaroid of my year in reading, of novels surreptitiously found in small independent bookstores and through the omnipotence of King Algorithm at the rainforest website, in the Squirrel Hill Library and mailed to me as ARCs from long suffering publicists. Some are big hits pushed by the Big Five with all of the requisite blurbs, some are quieter releases; a few are brand-new (or not even released yet), while others were on everybody’s reading list long before I got to it, but if it’s profiled in this essay it means that it was something that I digested in the last twelve months that was well-written enough to leave a bit of literary heart-burn.

In previous iterations of my “Year in Reading,” I’ve often tried to thematically tie together the multitude of books which I’ve encountered, perhaps inevitably falling victim to the literature professor’s propensity to insist on an argument, to organize my thoughts into a syllabus of sorts. Because of the years we’ve been having these last several cycles around the sun, the themes I’ve most often identified have veered towards the apocalyptic, but whether that’s because of the publishing industry’s current interests or my own obsessions, I can’t proffer a complete hypothesis (maybe it’s a bit of both). Nonetheless, I did notice certain recurring melodies in the work that most stuck with me this year, from the featuring of unreliable first-person narrators to a fixation on the costs of technology in late capitalism. And, of course, the apocalyptic as well.

The first book is actually the final novel that I read this year, a title which appeared on any number of “Best of Lists” (including those of The New Yorker, NPR, Publishers Weekly, and Vulture, among others) but which seemed to more evenly divide the commentariat online – Catharine Lacey’s audacious, post-modern faux-scholarly work Biography of X. Ostensibly a biography penned by the widow of a celebrated pseudonymous multi-media artist (equally adept in music, painting, and literature) during the heyday of the downtown art scene in 70s and 80s Manhattan and who only goes by that mysterious algebraic variable named in the title. Biography of X is a post-modern maximalist experiment deploying footnotes and other paratextual apparatus in the tradition of Vladimir Nabokov in Pale Fire or Mark Danielewski in House of Leaves, with a puckish humor and attraction towards invented academic discourse in the manner of Jorge Luis Borges and the integration of photography as with W.G. Sebald. A seeming amalgamation of figures as varied as Kathy Acker, Renata Adler, Patti Smith, Susan Sontag, and Marina Abramovich, the history of X’s New York bohemians diverge radically from our own world. Lacey’s novel is set in an alternate history where the former Confederate States secede following World War II and a literal wall divides the North from the South, with the former a progressive haven (Emma Goldman is FDR’s Chief of Staff) while the later becomes a theocratic and fascist state where a majority of the population spends part of their lives imprisoned over infractions as minor as skipping church attendance to being caught reading a prohibited book.

Predictably X’s widow and biographer C.W. Luca discovers relatively quickly that the artist was born in the Southern Territories which at the ostensible 2005 publication date of the book are slowly being reintegrated into the United States after the collapse of the former’s government. Independent of the socio-political issues engaged by Lacey (and Luca), The Biography of X is concerned with the intensity of artistic creation and genius, and what it means to be in the orbit of such magnetism. The attraction of Luca to her late wife “wasn’t love, nor was it lust or obsession. It was something both visceral and beyond viscera.” Criticisms of Biography of X have focused on the unbelievability of the alternate history which Lacey describes, or the inability of the preposterously talented X to match up to the effusive praise offered by contemporaries from David Bowie to David Byrne. For sure it strains credulity to believe that X would be able to listen to Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon in an alternate universe where Elvis never left the South or that an artist of the titular character’s magnitude should find herself involved with almost every major American avant-garde movement of the last decades of the twentieth-century.

Yet such complaints, I think, entirely miss the point. Biography of X is alternate history less in the sense of Philip Roth’s The Plot Against America or Michael Chabon’s The Yiddish Policeman’s Union than it is allegory, fable, fairy-tale. The America described by Lacey is fairly clearly our America, its spiritual dichotomies merely literalized. As for X’s genius, to interpret her as a kind of radical feminist Zelig who happens to find herself continually reinventing American art, literature, performance, and music is to imbue her with more personality than Lacey intends. As is the nature of allegory, X isn’t a person so much as a type, indicated by the bisecting lines of the letter which she goes by. Solve for X and X marks the spot – she isn’t an artist, she is all American artists, a distillation of the cultural genius that dominated our nation’s largest metropolis when CBGB was filled with punks and the Factory was filled with artists. “X believed that making fiction was sacred,” writes Lacey, and “she wanted to live in that sanctity.” By that standard, Biography of X is positively holy.

Booker Prize-winning translator Jennifer Croft’s first novel The Extinction of Irena Rey (not out until February!) bares some similarity to Biography of X. As with Lacey’s novel, the narrator of The Extinction of Irena Rey is a younger, unreliable narrator infatuated with an older artist, in this case the celebrated and enigmatic Polish novelist Irena Rey. In this case the narrator is an Argentine translator summoned to Rey’s dacha along the edge of the primitive, ancient Bialowieza Forest on the border with Belarus. The narrator is initially known only as “Spanish” for the language of the translator; indeed all of the characters are named for the tongue to which they most mold the author’s words (there is an “English,” a “Czech,” a “Swedish,” etc.). Responsible for collaboratively translating the last several of Rey’s books, as if they were the seventy scribes of Ptolemy responsible for the Greek Septuagint, there is something cultish and disquieting about this literary coterie’s devotion to Rey, especially that of Spanish (whose real name we learn is Emi) who unironically refers to her hero as “Our Lady of Literature.”

As with Lacey’s novel, Croft includes an ingenious paratext to The Extinction of Irena Rey, whereby we’re reading Emi’s account as translated into English by her nemesis, who frequently comments on the narrative through a prodigious application of footnotes. When Rey goes missing, Croft describes the interactions of the translators as a dark comedy, a claustrophobic gothic romance where this assortment of scholars resides in the atmospheric gloom of the forest while debating whether or not to continue work on Rey’s latest novel entitled Grey Eminence, which deals with climate change, even as its author is missing, perhaps kidnapped or dead. Not uncoincidentally a translator of Polish and specifically Argentine Spanish, Croft is rightly celebrated for her renditions of Olga Tokarczuk, as well as her advocacy on behalf of translators being acknowledged as practicing an indispensable creative act. Read in that light, The Extinction of Irena Rey can be understood as both a playful and unnerving encomium to the power of translation, to the ways in which scholars attempt to convert one tongue into another, but also how they grapple with the fundamental ineffability of language and the unknowability of our fellow humans.

Throughout The Extinction of Irena Rey, the reader can’t help but question the motivations of Emi, especially because of English’s footnotes (though we also question the latter’s motivations). Both Luca in Lacey’s novel and Emi in Croft’s could be called “Daughters of Ottessa” after Ottessa Moshfegh, the creator of disturbing unreliable narrators in works like Eileen and My Year of Rest and Relaxation. Moshfegh is a crafter of diseased consciousnesses every-bit the equal of Poe or Dostoevsky, but by filtering this unreliable narration through women rather than through oh-so-serious-young-men, she has perfected a new type of character, a variety of feminine anti-hero that for too long was absent from literature. Both Croft and Lacey have done something similar to Moshfegh in their respective works, as has Bea Setton in her slender but rich novel Berlin. Evocative of novels both midcentury and existential, Berlin could easily feel as if it took place forty or fifty years ago were it not for the narrative sometimes requiring a cellphone. Setton’s novel is narrated by Daphne, a twenty-something Anglo-French failed graduate student who has attempted to escape romance issues in her native London by pulling a geographical to the German capital. There, in arguably Europe’s most cosmopolitan and decadent of metropolises, Daphne takes German-language classes and lazily toggles about her scant social scene. In a manner that reminded me of Moshfegh’s narrator in My Year of Rest and Relaxation, it’s clear that Daphne’s psychology is fractured, that there are issues of continuity and memory in her accounts, that a pretty clear eating disorder and substance abuse problem makes her sense of self shaky at best, while she thinks little of abjectly lying to her most intimate friends and partners.

Thrumming with an anxious paranoia, Berlin is beautiful but cold, evocative but ominous. Daphne is haunted by absence in Berlin, for “I expected my suffering to feel redemptive in some way. I thought life was meant to be meaningful,” but Setton’s novel is brave enough to consider that maybe it isn’t. The backdrop to Rene Branum’s Defenestrate is another elegant European capital, this time appropriately Prague (with interludes in the Pacific Northwest). Branum’s novel is narrated by Marta, enmeshed in a codependent relationship with her gay brother Nick, the two absconding from the United States to the Czechia of their family’s ancestry, pursued by their mother’s claim that the family was cursed with a propensity to fall out of, or off of, or from things. The delicate wedding-cake beauty of this foreign city serves to alienate Marta much as Berlin was alienating to Daphne, while both are marked by less of a deficit in self-awareness than a lack of understanding where their awareness should be focused. Lyrically written, Branum’s novel is an exploration of the equivalence of flying and falling.

Another master of epistemological flux is Rebecca Makkai, arguably one of the most talented writers today. Her 2018 National Book Award and Pulitzer Finalist The Great Believers is an astoundingly gorgeous and heartbreaking epic about the AIDS pandemic, exploring how the disease decimated a group of friends living in the gay community of Chicago’s Boystown during the 80s and 90s. Worthy of being included among nonfiction accounts of AIDS like Randy Shilts’ 1987 classic testimonial And the Band Played On: Politics, People, and the AIDS Epidemic, Makkai (who is not a gay man) was fortunate to have had her book published before the cultural “wisdom” emerged that reduced a creative writer’s subject matter to only their immediate environs, or more drearily their identity. In The Great Believers Makkai takes care to express an ethic of being an outsider, looking in at a community to which her central character Fiona is an ancillary (her brother Nico first dies of the disease followed by most of his friends), so that the novel is a triumph of empathetic representation rather than appropriation.

Shifting between the 80s and the contemporary moment of the book’s publication, Fiona straddles these decades, remembering Nico and especially his friend Yale who worked as an art curator, while thirty years later she takes stock of those who died and those who survived, all while trying to reconcile with her estranged daughter. A potent meditation on love and trauma, family and death, The Great Believers is ultimately a paean to this community left to die and the entire generation decimated by government callousness. Makkai’s tenderly rendered portrayals of closet queens and proudly out-divas, of butch suburban homosexuals and of Mattachine respectability pols alike is obviously political, but it’s deeply human as well. “It’s always a matter, isn’t it, of waiting for the world to come unraveled?” writes Makkai. “When things hold together, it’s always only temporary.”

The much anticipated I Have Some Questions for You is a similarly subtle and nuanced take on political and social issues. An author admirably allergic to didacticism, Makkai’s writing is never moralizing and certainly not agitprop, for just as in The Great Believers her allegiance is to characters rather than dogma, so as in the unfortunately titled I Have Some Questions for You she is able to explore contemporary issues like so-called cancel culture, #MeToo, social media, and true crime obsession without resorting to crude dichotomies, for “Life isn’t that messy if you stay away from mess.” Written as an account by one Bodie Kane, successful film professor and graduate of an exclusive New England boarding school, I Have Some Questions for You has its main character returning to her alma mater’s campus to both teach an intercession course and to explore and ultimately produce a podcast about the brutal murder of a beautiful classmate decades ago. Both uncomfortable and introspective, I Have Some Questions for You captures our particular moment with uncanny precision.

R.A. Kuan’s delicious satire Yellowface also interrogates the digital narcissism and identitarian predilections of our current age in her squirmingly enjoyable Yellowface. Narrator June Hayward is one of the great first-person voices of this decade, a character who if not quite a sociopath certainly has moments of being sociopath-adjacent. A struggling writer who obsessively compares herself to her college friend Athena Liu, the recipient of literary plaudits and laurels for her brilliant explorations of Asian-American identity, June steals an unpublished manuscript from Athena’s apartment after the later chokes to death. Convincing herself that her edits to the manuscript – a novel about the contributions of conscripted Chinese laborers during the First World War – are a form of cowriting, June passes off the work as her own and achieves the literary success which she always coveted. Unscrupulous agents, editors, and publicists purposefully play up the very white Hayword’s supposed ethnic ambiguity with artfully done author photo shoots and by having the book published with her hippiesh middle name as “June Song.”

June isn’t entirely lauded however, as critics and activists criticize her wanton acts of cultural appropriation, and as reporters begin to piece together the scope of the author’s deceptions. Obsessed with the social media scrum over her work (or rather her perceived work), June spirals into the serotonin addiction of likes and retweets, continually googling herself and thriving off both the love and hate directed towards her. “But Twitter is real life,” June justifies, “it’s realer than real life, because that is the realm that the social economy of publishing exists on, because the industry has no alternative.” A trenchant meditation on comfortable white aggrievement and the culture industry’s racial tokenism, on the Goodreads Industrial Complex and the Big Five’s bottom line, the nature of literary celebrity and the mechanics of the social media pile on, Yellowface is an exhibit on how the literary novel is able to say things – or at least imply, suggest, and explore things – that other modes of writing (say the newspaper column) are incapable of. Partner to June’s diseased brain, we can never forget the horror of what she’s done and continues to do (and the depths she’s willing to fall so as to maintain her own illusions), and yet she is never monstrous. At its core, Kuan’s novel is animated by the verity that “Writing is the closest thing we have to true magic,” where publishing itself can ironically conspire to obscure that salient reality.

Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin is similarly aware of the magic of narrative, albeit not in literature but rather video-games. Arguably the first great novelistic exploration of that too-often maligned medium, Zevin’s book does for video games what Chabon’s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay did for comic books – explain the semiotic power of the form for a literary audience too enamored with their own skepticism. Following platonic lovers and partners in video game development Sam Massur and Saddie Green over three decades, from a Koreatown youth to Harvard Square and back to Los Angeles, Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow wrings pathos from programing, the entire book not just about friendship and betrayal, but also an aesthetic argument for the power of video games. With several convincing descriptions of games developed by Saddie and Massur over the course of their career – including a moving title about a Japanese child trying to save his family that has shades of Hayao Miyazaki – Zevin’s novel is fundamentally about the restorative power of narrative, the ways in which the stories we tell about reality, be it in a novel, video game, or personal memory, can be both redemptive and damning. “What is a game?” asks a friend of the duo. “It’s the possibility of infinite rebirth, infinite redemption. The idea that if you keep playing, you could win. No loss is permanent, because nothing is permanent, ever.”

A different type of memory is presented in Samuel Ackerman’s unusual American parable Halcyon, an alternative history in which technology has cured death and the living are forced to grapple with the conquering of loss that ironically signals a greater loss. Martin Neumann is a history professor at a small liberal arts college in southern Virginia, renting a guest house on the property of the plantation of Robert Ableson, a prominent lawyer and one-time liberal lion who advocated for civil rights in the Jim Crow-era South. Set in an alternate history where Al Gore is the winner of the 2000 election, investment in stem cell research has effectively allowed for the resurrection of the recently departed, which Neumann discovers includes his late-night bourbon and conversation partner Abelson. Ackerman is refreshingly light on details when it comes to the mechanism that restores life, this device more literary than scientific, which gives Halcyon an allegorical feel, Franz Kafka as filtered through William Faulkner. A postmodern Southern gothic, Halcyon is concerned not with the technology that gives life back after it has naturally passed away, but rather with Faulkner’s famed contention that the past is never the past. Pivoting around a campaign to remove the equestrian statue of General Robert E. Lee from Monuments Row in Richmond, Neumann discovers that there were limits to Abelson’s supposed progressivism (and his own as well), as the endurance of both people and ideas who long should have departed is less resurrection than it is haunting.

“The past cannot be forgotten,” wrote philosopher Mark Fisher in Ghosts of My Life: Writing on Depression, Hauntology, and Lost Futures, “but the present cannot be remembered.” Fisher’s thinking was focused on the manner in which neoliberalism precludes imagining a better future, how we’re haunted by potentials for different ways of doing things which seem forever deferred. A trio of novels I read this year were concerned precisely with the late capitalist predicament, the way in which imaginary numbers on a screen and very real materials in the earth shape and limit the contours of our lives, of our thinking. Jonathan Miles’ Want Not, Andrew Ridcker’s Hope, and Adam Wilson’s Sensation Machines are all what could be called post-08 novels, works that with a millennial’s sense of cynical disappointment give voice to the hypernormalization whereby we all realize how American capitalism is spent, but we’re also completely incapable of envisioning anything else. Want Not is composed in three ingeniously braided storylines that are propelled towards a conclusion by Miles’ narrative logic; they include a pathetic middle aged linguistics professor grappling with both his divorce and his father’s Alzheimer’s, an anarchic freegan couple living off the detritus of wealthy Manhattanites, and a magnate who has propelled himself into Westchester luxury through debt-collection. If none of these characters are entirely likeable, nor are they totally heinous, for the biggest character in Want Not, if you will, is our culture’s propensity to waste – money, materials, people. “This is our condition,” writes Miles. “We do not solve problems. We replace them with other problems.”

Ridcker’s Hope takes places in a similar milieu as Miles’ New York of this century’s teens. The Greenspans of Brookline, Massachusetts are, in keeping with their community, wealthy and good liberals, yet just as the title of Ridcker’s novel pokes fun at the lost promise of the Obama years, so too does the family inevitably fall short of their own highest ideals, disappointment the inevitable affliction of the optimist. The father Scott is a successful surgeon indicted for falsifying data in a medical study, his wife Deb is an immigrant rights activist who has left her husband for a celebrated feminist poet, while daughter Maya inexpertly attempts to make her bones in the New York publishing industry and son Gideon is a depressive college dropout searching for meaning (and finding it incongruously in Kurdistan). As with Miles, all of these lost characters are all the more powerful because they’re forgivable, as is also the case with the couple at the center of Adam Wilson’s Sensation Machines. Taking place in a reality just slightly askew from our own, perhaps a few years (or months) into the future, Wilson’s novel concerns Eminem-obsessed finance bro Michael Mixner and his wife Wendy who works for a publicity company, the wealthy couple making their home in fashionable Brooklyn even while the country is in economic free fall. As the couples’ personal tragedies play out – from miscarriage, to bankruptcy, to the murder of Michael’s childhood friend – the country is convulsed by an economic populist uprising in response to the mass unemployment caused by automation and artificial intelligence. A reinvigorated #Occupy approaches the brink of success in advocating for congressional legislation on behalf of a Universal Basic Income. while nefarious corporate forces consolidate the power of surveillance capitalism and the all mighty sovereignty of the algorithm. The Mixners lives intersect with these broader economic and social forces, with Wilson asking how much agency any of us really have in swimming upstream against the current of inequity. Wilson provides reportage from our empire in decline, of the “end my friend and here we are: the fall of Rome, the decline of derivatives, the rise of dildos made from real human skin.”

Of all the books I read in the past twelve months which squarely take stock of our current predicament, none could quite compare in scope, ambition, and execution like Stephen Markley’s nearly nine-hundred page door-stopper The Deluge. Beginning at the turn of our century and ending decades hence, Markley’s novel is the most vital and propulsive climate fiction ever published, an intricate nineteenth-century social novel about the environment, social politics, and capitalism, wherein a dozen interweaving narratives from a scientist studying global warming to an autistic computer scientist, a group of green terrorists and a publicist working for the fossil fuel industry, bare witness to ecological collapse. Inevitably compared to Kim Stanley Robinson’s far inferior The Ministry of the Future, Markley’s book is rather clear-eyed about the sheer scope of ecological degradation that we currently face, and the noxious, authoritarian social currents that our apocalyptic moment has given birth to.

Written in a variety of styles, from Dickensian third-person omniscient to found document, David Foster Wallace-like footnoted scholarly works to page-turning action sequences (including a depiction of Los Angeles’ complete immolation), The Deluge is the great epic social novel of the Anthropocene. Markley’s scope is galactic, from Capitol Hill to the canals of Venice, rural Ohio to the burnt streets of California. The Deluge is science fiction of the present, a reportage of the polycrisis, an obituary for our civilization. Markley’s work is all-encompassing, pivoting beyond the myopia of social media or the machination of predatory capitalism to nothing less than the extinction of humanity and everything else in our biosphere, yet he is intimately attuned to the granular details of his characters’ lives. Markley is not entirely hopeless, yet he’s blunt on the score, and the future that he envisions with everything from massive derechos and fires killing thousands in a day to the incipient rise of genuine American authoritarianism is disturbingly relevant. With the chilling prescience of Casandra, Markley writes that “Violence against nature always goes hand in hand with violence against people.” This year I was reminded that truly great literature can be many things – jeremiad and manifesto, incantation and conjuration, warning and prophecy – but that it’s never merely an escape.

Ed Simon is the editor of Belt Magazine, an emeritus staff-writer for The Millions, and a columnist at 3 Quarks Daily. The author of over a dozen books, his upcoming title Relic will be released by Bloomsbury Academic in January as part of their Object Lessons series, while Devil’s Contract: The History of the Faustian Bargain will be released by Melville House in July of 2024.