by Peter Topolewski

Isn’t it time we talk about you?

Isn’t it time we talk about you?

You.

A collection in the realm of 4.5 x 10^27 atoms. A portion of your hydrogen and helium atoms originated in the Big Bang, 14 billion years ago. The heavier elements in you, the stuff of life, the carbon and nitrogen, they came from stars. From exploding stars, in fact. The dying blasts of stars in distant galaxies accounted for perhaps a smallish measure of your atoms. Most came from stars exploding in the Milky Way, and above all from a single super nova that preceded the existence of our own star, the Sun. Like all the others, it was a super nova without a name, one we’ll never know, but one we should be especially grateful for. It was amazing wasn’t it, generous, as Thomas Berry would say, giving itself away without asking?

It gave me you.

Extraordinary, those 4.5 trillion quadrillion atoms in you, from across the cosmos, they’re mostly empty space. Take away the space, and all of them together would be no larger than a single biological cell. As far as those atoms have traveled, as large as the universe has grown, there is, as Duane Elgin wrote, more smallness in you than there is bigness beyond you. On our cosmic scale, you are a giant.

In a photo I’m blessed to have, you’re five or six years old, standing near a farmhouse. Anyone who looked at it would say you’re little, but really you’re a giant. Who are you in that photo?

I could believe I came about randomly, through trial and error, but not you.

You are the atoms in that photo, but much more.

In another picture, you are in your twenties, alone on a chair in a living room, pensive and beautiful. All the atoms you contained when you were six and seven and eight years old, they’re gone, given over to the environment, replaced with others wholly new to you. In that frozen moment, your eyes are on a place only you can see, your mind on thoughts, hopes, concerns I cannot reach.

Who were you?

If you can be composed of other atoms and still be, you can be any atoms, can’t you? And if you can be any, can’t you be all?

Who are you?

You are atoms and more. Read more »

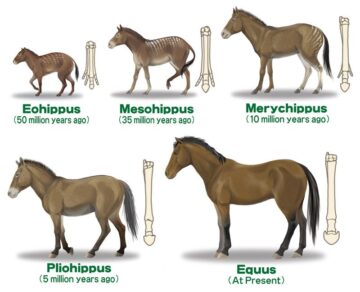

To be alive is to maintain a coherent structure in a variable environment. Entropy favors the dispersal of energy, like heat diffusing into the surroundings. Cells, like fridges, resist this drift only by expending energy. At the base of the food chain, energy is harvested from the sun; at the next layer, it is consumed and transferred, and so begins the game of predation. Yet predation need not always be aggressive or zero-sum. Mutualistic interactions abound. Species collaborate when it conserves energy. For example, whistling-thorn trees in Kenya trade food and shelter to ants for protection. Ants patrol the tree, fending off herbivores from insects to elephants. When an organism cannot provide a resource or service without risking its own survival, opportunities for cooperative exchange are limited. Beyond the cooperative, predation emerges in its more familiar, competitive form. At every level, the imperative is the same: accumulate enough energy to maintain and reproduce. How this energy is obtained, conserved, or defended produces the rich diversity of strategies observed in nature.

To be alive is to maintain a coherent structure in a variable environment. Entropy favors the dispersal of energy, like heat diffusing into the surroundings. Cells, like fridges, resist this drift only by expending energy. At the base of the food chain, energy is harvested from the sun; at the next layer, it is consumed and transferred, and so begins the game of predation. Yet predation need not always be aggressive or zero-sum. Mutualistic interactions abound. Species collaborate when it conserves energy. For example, whistling-thorn trees in Kenya trade food and shelter to ants for protection. Ants patrol the tree, fending off herbivores from insects to elephants. When an organism cannot provide a resource or service without risking its own survival, opportunities for cooperative exchange are limited. Beyond the cooperative, predation emerges in its more familiar, competitive form. At every level, the imperative is the same: accumulate enough energy to maintain and reproduce. How this energy is obtained, conserved, or defended produces the rich diversity of strategies observed in nature.

We humans think we’re so smart. But a

We humans think we’re so smart. But a Giant Tarantulas

Giant Tarantulas

by Steve Szilagyi

by Steve Szilagyi Jaffer Kolb. Lake Mývatn, October 13th, 12:08 am.

Jaffer Kolb. Lake Mývatn, October 13th, 12:08 am.

A recent news story about the fate of Ernest Shackleton’s ship

A recent news story about the fate of Ernest Shackleton’s ship