by Azadeh Amirsadri

For about six years now, since a cancer diagnosis put what really matters in life in perspective, I have finally made peace with myself and especially my body. I have accepted my directness in most situations, even though shyness and false innocence were valued in my adolescence, in the culture where I grew up. I have embraced being told that “I tell it as it is,” and learned to look away at the judgment that comes with that description: basically, not being savvy enough to enrobe the truth in a softer garment. Dancing around real issues and pretending the elephants are not lined up to enter the room has never been my strength, yet I also value the ability to soften blows when needed.

My body, unlike my mind, has had a different trajectory in this journey. From being looked at and leered at, to being touched and loved, to being sexualized, to being criticized, I finally began to recognize who I was, outside of my body. I took the reins I had given away freely to others and called her my own, reclaiming her and making her my friend and confidante instead of the burden she had become. I wrote a list of things I felt I had to apologize for, and every time my body felt unloved for whatever reason, either by me or by others, I went back to my list and comforted her.

Dear body,

I apologize for feeding you when you weren’t hungry for food, but wanted love and acceptance. Food and alcohol sometimes took the pain of loneliness away, especially during the long years of being the only parent in attendance at my youngest’s choir performance or at his soccer games. Food comforted my child and me as we navigated those years together. I created a pseudo family with some people, but I didn’t always feel connected to them, yet I thought it was better than not having anyone.

I apologize for putting cigarette smoke in your face and lungs when you were younger and wanted to flirt, but was insecure. Smoking was a cover-all for stalling a difficult situation, ready to leave a risky place, and sometimes needing extra time to plan my exit. I smoked so much at an outdoor party one evening that the inside of my mouth hurt, yet I didn’t have the courage to say that I didn’t belong there. Trying hard to blend in and fit in, when all I needed was a familiar and kind person to hold my hand and lead me away. Read more »

We sometimes say that someone is living in the past, but it seems to me that the past lives in us. It lives in our houses; it lies all around us. As I write this, I’m sitting on the couch under two blankets crocheted by my grandmother, who was born around the turn of the 20th century. The laptop sits on a folded blanket that came from Mexico via a friend years ago. And that’s just the surface layer. My closets and file cabinets are also full of the past.

We sometimes say that someone is living in the past, but it seems to me that the past lives in us. It lives in our houses; it lies all around us. As I write this, I’m sitting on the couch under two blankets crocheted by my grandmother, who was born around the turn of the 20th century. The laptop sits on a folded blanket that came from Mexico via a friend years ago. And that’s just the surface layer. My closets and file cabinets are also full of the past.

Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,

Sughra Raza. Bey Unvaan. January, 2026.

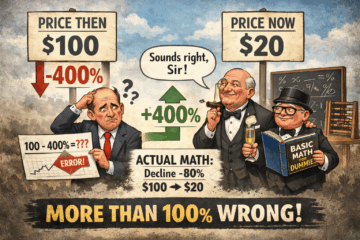

Sughra Raza. Bey Unvaan. January, 2026. Oy. Where to start? Let me begin with a recent abuse involving percentages. Trump’s absurd claims about price declines of more than 100% have elicited a lot of well-deserved derision. How could someone with an undergraduate degree in business from Wharton make these mathematically impossible claims?

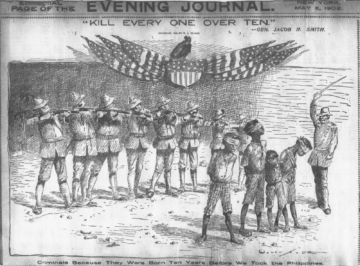

Oy. Where to start? Let me begin with a recent abuse involving percentages. Trump’s absurd claims about price declines of more than 100% have elicited a lot of well-deserved derision. How could someone with an undergraduate degree in business from Wharton make these mathematically impossible claims? In almost every medical school in the world, there is a cupboard—or a quiet back room—full of bones. The skulls are numbered, the femurs stacked like firewood, the ribs threaded onto metal wire. Officially, they are “teaching aids”. Unofficially, they are the remains of actual lives, reduced to objects that can be ordered from a catalogue.

In almost every medical school in the world, there is a cupboard—or a quiet back room—full of bones. The skulls are numbered, the femurs stacked like firewood, the ribs threaded onto metal wire. Officially, they are “teaching aids”. Unofficially, they are the remains of actual lives, reduced to objects that can be ordered from a catalogue. 2025 was a good year for books.

2025 was a good year for books.