by Dick Edelstein

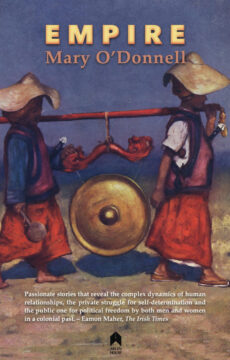

A number of books published in Ireland in the past few years relate to the centenaries of the First World War and the fight for Irish independence. Apart from being an opportunity to sell books, the conjuncture afforded readers an opportunity to reflect while delving into a receding page of history. Mary O’Donnell’s narrative collection Empire includes interlinked short stories dealing with the revolutionary period, along with a novella-length title piece. Notwithstanding its historical tie-in and informative potential, the true raison d´être of this book is the pleasure of reading.

A number of books published in Ireland in the past few years relate to the centenaries of the First World War and the fight for Irish independence. Apart from being an opportunity to sell books, the conjuncture afforded readers an opportunity to reflect while delving into a receding page of history. Mary O’Donnell’s narrative collection Empire includes interlinked short stories dealing with the revolutionary period, along with a novella-length title piece. Notwithstanding its historical tie-in and informative potential, the true raison d´être of this book is the pleasure of reading.

All of the stories are eminently readable, as we can clearly see in the title piece. During the First World War, the Wheelers, an Irish newlywed couple, travel to Burma, where the husband takes up an engineering job with a British company on a three-year contract. Separately, both of the protagonists become aware of their growing distaste for the prevailing colonialist attitude towards the local population, and both in the end are compelled to reflect on their own sense of identity, but in very different ways.

The spare writing vibrates with unstated meaning as the narrator’s tone mirrors the characters’ circumspect manner of speech. We can almost hear their inner dialogue as they delicately choose what to communicate to each other and what to leave unsaid. Gaps left by unspoken thoughts cast shadows of social norms and propriety, highlighting the contrasting postures of men and women imposed by the social roles they feel obliged to embody. Whether the characters’ modulated diction is informed by historical research or by the author’s poetic sensitivity to language, the verisimilitude of the portrayal is palpable, and it is reinforced by a carefully created atmosphere. Craft is concealed by art, as when viewing a finely painted image whose effect we perceive immediately without discerning the brush strokes.

The treatment of this story is novelistic, particularly in terms of character development, setting, atmosphere and storyline. Once comfortably engaged in the unfolding of the tale, some readers may wonder why this highly engaging story has not been written as a full-length novel. Only at the end will they find an answer to that question. Once she has returned to Dublin after her colonial adventure, Margaret Wheeler has clarified her thoughts about the currently acceptable roles for women and about her future plans: to her husband’s surprise and consternation, she has decided to take up studies at a university. The author has posed a conflict in such a way that a denouement of any sort might blur the clarity with which it has been set up, so it is fitting that this tale of the evolution of the main characters’ attitudes—and of their separate reflections on their own identities—should end in such a way, in media res.

The book is more than just a collection of stories since they are interrelated through characters that link them, and this conjunction of fragmentary portrayals affords readers a clearer view of the confluence of historical and political currents and of how this conjuncture affected people’s lives in different ways.

The Irish Uprising and the Civil War in its aftermath were fought again in 2016, this time with no real casualties. The centenary celebration of nationhood going on in Ireland at that time heightened people’s awareness that many national myths needed some polishing up, at the very least, before being held up to the eyes of a 21st century world, but it was impossible to get everyone singing from the same hymn sheet since some citizens wanted to remember and honour only republican supporters in the conflict while others had sympathy for all of the people who had suffered on account of being drawn into it. If dustups in side streets were just barely avoided, there was little restraint shown when it came to bullying by ideological hardliners. Among other nationalists, some followers of Sein Fein—a less user-friendly party nine years ago—did not want to remember those who were drawn, however unwittingly, into the role of fighting against republicans—or siding with their enemies—even when some of those unfortunate souls were barely conscious of the role they were playing in a larger political framework. In this scenario, Mary O’Donnell finds a useful role for literature: rather than waving placards, she sketches out a nuanced portrayal of the ways in which a complex historical situation diversely affected a number of people of different stations and social class. The author avoids polemic, aiming to shed light on past events that are laden with ambiguity.

Through the lives and experiences portrayed in these stories, readers are able to view the events of the revolutionary period from several viewpoints, and this is a useful exercise in itself. Without needing to look further, we can appreciate the potential dangers that still loom as the force of demographics in Northern Ireland has led implacably towards a shifting majority and a new balance of power, a crystal-clear example of the importance in today’s world of being able to view political situations from multiple viewpoints.

In a story entitled “Fortune on a Fair Day”, we meet a young man who falls in love, probably for the first time. He decides to join the British army just after the execution of the leaders of the 1916 Easter Rising. His family and friends are divided over his decision, and some see it as folly or even treason. Folly it may be, but the young man’s decision aptly illustrates the sort of situations that occurred in the midst of the political currents of the time, and this lesson in history may be particularly of interest to readers who are less familiar with some of the nuances of the Irish political scene and the historical complexities of the revolutionary period.

Empire, O’Donnell’s third short story collection, is an engaging and highly readable addition to a serious body of work that includes seven poetry volumes, four novels, and a corpus of critical writing and journalism. To readers interested in knowing more about O’Donnell’s writing, I recommend the references cited below.

Empire by Mary O’Donnell, Arlen House 2018.

Giving Shape to the Moment: The Art of Mary O’Donnell, Poet, Novelist and Short-Story Writer. Edited by María Elena Jaime de Pablos. Oxford: Peter Lang, 2018.

Giving Shape to the Moment: The Art of Mary O’Donnell, Poet, Novelist and Short-Story Writer, review by Asier Altuna-García de Salazar of the University of Deusto (Bilbao), Spain, published in issue number 14 (17 March, 2019) of Estudios Irlandeses, open-access journal of the Spanish Association for Irish Studies (AEDEI).

Note: A previous version of this review was published in the Irish-British journal The Blue Nib, in both the print and online editions of Issue number 39, but the digital version is no longer accessible on the web since that much loved journal has ended a good run lasting several years. Thus, we are now publishing this revised and updated version of my original review since the book it deals with, although prominently reviewed in The Irish Times at the time of its publication, deserves broader critical notice, and this situation highlights the dismal fact that just a very small handful of Irish writers, whose names are familiar to the worldwide reading public, get significant attention in the press and media.