by Jochen Szangolies

Politics does not come naturally to me. Part of it is because I have a tendency to be interested mostly in the view sub specie aeternitatis, in the deep truths of the world, what it is, what we are, and how it all hangs together, rather than in the accidents of human squabbling. I like to uphold an idealized image of myself as engaged in the pursuit of Truth and Beauty, and there seems to be little of either in politics.

Yet this is a stance of luxury. An ideal world may permit the secluded scholar in the ivory tower to disengage from worldly affairs, safe in the certainty that everyone’s base needs are met. But we very much do not live in this world: people suffer needlessly because of bad politics. To disengage is to be complicit in this suffering, in the last consequence. So while, with the late, great Daniel Dennett, I begrudge every hour spent worrying about politics, I find it rarely leaves my mind these days, romantic pursuit of capital-T Truth notwithstanding.

The other reason I prefer to avoid politics is that I’m not very good at it. The mode of thought that unravels complex interpersonal alliances, social scheming and behind-the-scenes maneuvering is difficult for me. Even in social settings, I often find myself having missed some subtext entirely obvious to others. This is self-reinforcing: my lack of interest feeds my lack of ability, due to not engaging with it enough to get better, and my lack of ability makes developing an interest difficult.

But there is an opportunity in being bad at things: it means you get to go slow. If you don’t grasp a mechanism in the large, break it down into its components; if you lack the intuition for great leaps, be explicit along every searching step. That way, sometimes, the outsider looking in might even notice something buried beneath the implicit assumptions just obvious to the seasoned practitioner (or expose themselves as a know-nothing out of their lane).

Thus I write about politics only with some trepidation and in the hopes that my own halting explorations might be of use to others who, like me, have been left dumbfounded by recent events.

To a good first approximation, it seems to me, politics is about power: where it comes from, who wields it, how it is exercised, and what it affects. In a true democracy, for instance, power comes from the people, is wielded by elected officials, exercised through strictly reglemented channels, and affects the conditions of life for the people in turn. An absolutist monarchy might derive its power from some higher edict, say by reference to the will of God, is wielded by the monarch, is essentially unconstrained in its exercise, and also affects the conditions of life for the people. Since the people get a say in the determination of their own circumstances in a democracy, and not merely ‘suffer what they must’ as in a monarchy, we think of the former as a more just system.

Taking the next baby step, then, we may ask about power. Broadly speaking, power is being able to act according to one’s will: to not have to take ‘no’ for an answer. If politics is about power, then it is about who is invested with the ability to see their will manifest. If we have an interest in improving the living conditions of everyone, the ideal politician would then hold the good of the many as the supreme object of their will.

One might be skeptical that such a person exists. But I want to make the case that, even if they did, the dynamics of power make it all but impossible for a situation in which ultimate power is exercised for the benefit of the many to be stable. Paradoxically, it is the limitations on power, and the attempts to overcome them, that is responsible for this.

Power And Its Limits

All power ends somewhere. Leaders of nations, even if they reign supreme over their people, have their powers curtailed by that of other nations—and any contest between these may lead to the exercise and comparison of power in its rawest, most physical form, as direct conflict in war. The powers of democratic leaders are reined in by law and constitution, with complicated systems of checks and balances. Any ability to exercise power stops where a greater power says ‘no’. To you and me, the thing that says ‘no’ to the realization of our plans might be a look at our bank statement; to the rich, it might be the law (ideally, at least), or those yet more powerful.

These can be circumvented by growing richer and more powerful, until no other has the power to say ‘no’ to you. To the hypothetical benevolent monarch, seeking more power may be reasonable: only thus can the greatest good for the many be achieved. Power, even with the loftiest of goals, always seeks more power.

But there is one final and absolute boundary, one thing that says ‘no’ even to the most powerful: reality. (Of course, the concept of reality is itself somewhat fraught. For present purposes, it will be simply whatever it is that ultimately says ‘no’.) No matter how rich and powerful you are, if you declare yourself able to fly and jump from your penthouse on the 57th floor of your Manhattan tower, reality will deliver a firm ‘no’ in the form of a grease stain on the pavement below.

Such a notion of reality holds great appeal to the scientist in me: to the extent that there is a ‘reality’ that figures into modern science, it’s that which decides whether your experiment will yield the expected result. If it says ‘no’, your theory is falsified and gets thrown onto the garbage-heap of good, but wrong ideas (well, again, ideally—such naive falsificationism is really a first approximation to actual scientific practice at best). Politics, of course, does not act in the arena of fundamental physics (regrettably, otherwise it might be much more interesting). But there are other layers of reality just as capable of delivering a sound ‘no’ to your aspirations. Suppose you’re in the company of others in a public place, like a café. Typically, you’ll be wearing clothing, and wouldn’t just take it off. Why is that? Because everybody around you expects you not to do so. Why do they do so? Because everybody around them expects them to feel that way. The reality that denies your ability to just take your clothes off wherever you please is a social reality, but not any less real (not any less capable of saying ‘no’) for that.

Reality is the ultimate check on power, but the nature of power is to grow unbounded. How do we resolve this? I think an argument can be made that the political history of the past 100 years or so can be read as a history of just this conflict—and the accompanying perversion of the exercise of power. (Of course, the past 100 years is something of an arbitrary frame—similar narratives have played out in different places at different times. But I believe the case is made especially transparent here, in part because our material power—our ability to impose our will on the world around us, to ‘move stuff around’—has soared to unprecedented heights, nearing the limits of actual physical possibility.)

Reframing Reality

If reality ultimately limits the exercise of power, yet power accepts no limits, something’s gotta give. But reality is not the sort of thing you can just go and change. So what can you do?

One solution is to recognize that the space of human action is not necessarily perfectly in line with reality: we act based on what we think is the case, because we don’t have any direct access to what is actually the case. If we say, with Wittgenstein, that ‘the world is all that is the case’, then this is not the world in which we actually live and act. So we might not need to change the world, to change reality, to increase power; we only need to change the way in which that reality affects us, and the way we act. We need to reframe reality, gloss it in some way that is accommodating to our aims.

This, I believe, is the great insight behind public relations (PR) (originally called, somewhat more honestly, simply propaganda), as conceived of largely by Edward Bernays, nephew to ur-psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud. I have touched on Bernays work, whose greatest hits include getting women to smoke ‘freedom torches’ and helping topple the Guatemalan government, before. There, my contention was essentially that successful PR manipulates not so much the facts, directly, but the affect those facts are perceived under. Thus, a neatly stacked, but otherwise fairly unremarkable lump of carbon atoms becomes a prized jewel by associating it with ideals of romantic love (plus some judiciously applied artificial scarcity).

Where reality would deliver a negative verdict, because e.g. cigarettes cause cancer, meaning there’s no good reason for smoking them, you make a reason for doing so to cover reality’s shortfall, by painting them as a symbolic gesture. PR thus increases power by robbing reality of at least some of its ability to inform our actions. By bringing the conditions of our acting under the purview of those exercising power, the ‘no’ of reality just fades away unheard. As Bernays himself put it, PR provides a way to engineer consent: influence the mandate of the masses in such a way as to ensure a desired outcome in disregard of the ‘ground floor’ realities of the matter.

Still, a benevolent exercise of power might appeal to this notion on the idea that sometimes, the masses have to be directed for their own good, on the grounds that on their own, they are incapable of acting in the right way. As Bernays put it in his 1928 book Propaganda:

No serious sociologist any longer believes that the voice of the people expresses any divine or specially wise and lofty idea. The voice of the people expresses the mind of the people, and that mind is made up for it by the group leaders in whom it believes and by those persons who understand the manipulation of public opinion.

But PR can only go so far. Eventually, the knowledge that cigarettes do, in fact, cause cancer became manifest in widespread prohibitions against smoking in public venues and on advertisements for smoking, causing cigarette consumption to drop in most of the world. Even if you reframe reality, it is still there to assert itself.

A step beyond PR in the ability of power to transcend the checks and balances of reality is detailed in Guy Debord’s seminal 1967 classic, The Society of the Spectacle. Its fundamental contention is that social reality has effectively been replaced with a mere representation: the spectacle that is fed to us daily, in form of TV, movies, game shows, advertising—but also of ‘news’ reporting of the latest celebrity scandals, and even of purported actual events, like political rallies or foreign affairs.

In the spectacle, social reality is replaced by relations between people mediated via spectacular images. It constitutes an ‘overlay’ of reality, hiding the actual facts of the matter, where real power originates, behind a layer of images designed merely to dazzle and distract. The ‘no’ of reality can thus hardly penetrate beyond the veil of performative affirmation, of consumer identities bought and sold on media platforms. If PR creates an enhanced reality, framed in the terms most beneficial to the aims of those in power, the spectacle provides a superreality, layered atop the ground truths. With that superreality being a creation of those in power, the voice of reality as a check to power becomes muffled. (There is much more to Debord’s thought that would warrant closer study; but for present purposes, it is the way reality as an arbiter of the exercise of power retreats behind the spectacle that is most relevant.)

Replacing Reality

If Debord’s spectacle muffles reality, it still remains a shadowy presence, and can be brought to the fore again by ‘spectacular’ counter-action, so-called détournement (literally, something like ‘diversion’ or ‘rerouting’). There, the images that comprise the spectacle are hijacked to make their own fake nature obvious, to parody their original intent, or to simply make them ridiculous and unworthy of being taken seriously. Thus, concerted grass-roots action can penetrate the veil of the spectacle by making it a part of its own imagery: pointing its own weapons at itself, reality reasserts itself as that which remains once the fakes are revealed as such.

Against this, a yet more insidious tactic incorporating the fake nature of its images has evolved. (I use this word deliberately, because I don’t think that this and further tactics are so much an invention, with a plan and purpose, as ‘natural’ developments: the ‘hopeful monsters’ of adaptation in the struggle between power and reality that happened to sufficiently further themselves to survive, and mutate again). As diagnosed by post-structural sociologist and philosopher Jean Baudrillard, this is the notion of hyperreality: an artificial ersatz-reality inferred precisely from the obviously fake, in the way that the existence of a copy suggests that of the original.

Baudrillard’s illustration of hyperreality uses the example of Disneyland: nothing about it seriously pretends to be real. It is a world composed entirely of obvious fakes, of representations and make believe. But in being obviously so, the spectator is put into a position of having seen through the flim-flam: clearly, this is not real, thus, reality must lie somewhere else—there must be some original all this is trying to copy. This inferred original is the ‘hyperreal’ in Baudrillard’s sense.

But the twist is that this hyperreality itself isn’t real—there is no original. Thus, as he puts it, hyperreality is ‘the generation by models of a real without origin or reality’. So, what is it that we infer from the obvious fakes we are served? Just the social reality we take ourselves to inhabit—a reality that is such that the fakes we discover could be exaggerated copies of it. A reality of law and order, of power emerging from the masses, of social security. Disneyland is a copy of an American ideal that doesn’t exist, and never did exist—but that we infer from its obviously fake nature.

The key conceptual innovation here is the role played by obvious fakes: where prior attempts to ensure the growth of power sought to furnish convincing surrogates, in hyperreality, the fake is deliberately obvious to guide the intuition of a real that it apes—which simply doesn’t exist. Whereas the spectacle merely obfuscates reality, the hyperreal replaces it.

As a little nod to the wider historical context I’m ignoring here, the hyperreal is of course not the first ersatz-reality furthering the pursuit of power (even if it remains one of the more subtle examples). Many religions, for example, hold the here and now as a ‘fallen’, debased place, with the world beyond this one playing the role of the ‘real’ reality. Naturally, it is there that we get to reap our rewards for playing by the rules in this world—which rules are, of course, dictated by the high priests and prophets, i.e. the powerful. (This also illustrates a key technique in keeping the masses complicit in their own bondage: the myth of meritocracy, the idea that if you’re just hard working and virtuous and talented enough, eventually, you, too, get to reap the benefits of power, of having your will made manifest.)

Remaking Reality

In the (admittedly sketchy) history as outlined so far, power has been gradually overcoming the ‘no’ of reality by shoving it more and more into the background, making the space of our actions one governed by those who exercise power. The next logical step is then the attack on reality itself.

This is the spirit encapsulated in the famous ‘reality-based community’-comment by an unnamed White House aide (widely believed to be George W. Bush’s senior advisor Karl Rove) to journalist Ron Suskind: ‘We’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality.’

But of course, historical facts casts doubt on this self-evaluation of power. Reality proved resilient, and many of the Bush administration’s overreaches, such as the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, do in retrospect not exactly seem to be the assertions of imperial power the speaker may have envisioned.

Another branch of remaking reality tout court, as yet nascent, is found in the virtual. Virtual reality is the dream of the powerful: there, nothing can ultimately say ‘no’. Given sufficient control over the parameters of the simulation, it is indeed possible to soar out of your penthouse window.

However, as mounds of scorn heaped upon Mark Zuckerberg’s flailing attempts at establishing this ‘meta’-reality show, technology simply isn’t there yet. And while to a certain extent our own reality has been experiencing a sort of virtualization, in that the presence of obstacles is no longer something to adapt to, but rather an undue imposition of reality on our own self-assertion, the direct replacement of reality by a construct in line with power remains so far unsuccessful. The project of remaking reality in power’s own image has, so far, failed. But that doesn’t mean the struggle doesn’t continue along different lines.

Reality Shattered

In discussions of the conduit of once-and-future president Trump, the sheer volume and obviousness of his incessant lies often takes center stage. It boggles the mind how he can ‘get away with it’, with the implicit conceit here being a corrective pull exerted by reality to hold him accountable for his constant disregard of truth.

Frequently, Trump has been analyzed as a bullshitter, in the philosophical sense of the term: after the American philosopher Harry G. Frankfurt, bullshit is a mode of expression aimed at a pragmatic end, without any regard to the truth of any statement made. While the liar shows concern for truth, even if in a negative sense, the bullshitter’s sole concern is their own immediate need. But this analysis falls short.

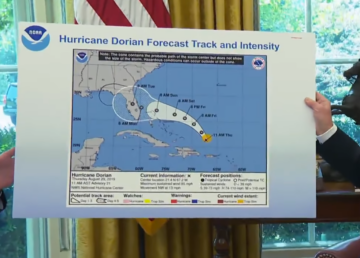

Trump—and others like him, such as Russia’s president Putin—lies not to further some distinct goal (or not primarily so), but lies, mainly, to lie—a constant ‘firehose of falsehoods’ designed to disseminate obvious untruths in high volume and intensity. In this, he makes—although probably not consciously—use of Baudrillard’s key insight of the utility of obvious fakes: that his lies are easily spotted as lies is precisely their point.

However, in contrast to hyperreality, the lies Trump spouts are not fakes of some imaginable reality—they are mutually contradictory, self-refuting, inconsistent: there is no original that they could be copies of. Rather than implying a reality curated to serve the interests of power, they shatter any conception of such a reality: in the space where the original should go, there is just a confused mess of broken shards and jagged pieces that can’t be assembled into a coherent whole.

If power cannot remake reality in its own image, it must destroy it, answer its resounding ‘no’ by flatly ignoring it, refusing even to acknowledge its possibility. Being bewildered at the barrage of lies, and lack of consequences, then just speaks to an expectation of the primacy of reality: but through a century’s effort, power has divorced itself from reality, has made its ‘no’ nothing but a faint whisper in the dark, bereft of any command.

It is here, also, that even the best intentions flounder against the expansion of power. Even for those starting out with the good of the many in mind—and I will leave it to the reader’s judgment whether any of the people in power currently belong to that group—will, in the last consequence, arrive at a point where the voice of reality no longer carries any heft. But with reality gone, what even is ‘the good of the many’?

After the shattering of reality, we are left free-floating in the void, desperately clinging to those closest beside us. There is no longer any ‘good’, or even a ‘many’, just us and them and the edicts of power. All that remains for us is to either align ourselves with it, or be crushed before it. The pursuit of power, even for the best of reasons, can only lead to the pursuit of power for its own sake: because in the end, nothing besides power remains.

It remains to be asked what we can still do, on the eve of the second Trump presidency. I have previously outlined a framework for collective action, in which it is ultimately mutual faith in each other that drives change. The reality of the world is not that we are a collection of disconnected individuals each desperately struggling on our own, no matter how much power wants us to believe so. In the absence of reality as a common source of truth, faith in one another allows us to act, and through our actions justify this faith: where reality has been robbed of a voice, it is up to us to say ‘no’. It’s a trapeze act, to be sure, but, as Kierkegaard would tell us, sometimes there is nothing left to do but leap.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.