by Martin Butler

Neurodiversity, a term first coined by the sociologist Judith Singer in the 1990s, is the idea that human beings think and act in a wide variety of ways which extend well beyond the narrow, stereotyped conception of ‘normal’ that most people take for granted. It has come to be regarded as a matter of minority rights, according to which people whose personalities or behavioural tendencies are atypical should be granted equal rights and the same respect as anyone else. Neurodiversity is an obvious reality to which there are two rather different approaches.

The first argues that we simply need to be more accepting of those who do not fit the standard way of being. It’s about overcoming the kind of prejudice we all know from the school playground against those perceived to be different. We might see this as widening the idea of what is acceptable and thus extending the spectrum of what is ‘normal’, for even within the range of what is described as ‘neurotypical’ there is diversity. There have always been different personality types – extrovert, introvert, impulsive, aggressive, thoughtful, calm, clumsy, methodical, and so on. These, however, are not described as neurodiversity but simply as human difference. Neurodiversity then, according to this first approach, simply means admitting more individuals into the normal range, such as those who have ADHD or those on the autism spectrum. It’s part of the wider ethic that being different, unusual, or even ‘odd’ is not in itself a reason to judge a person negatively. Importantly, this approach is an attempt to break down categories. Differences are seen as irrelevant to the way we judge, just as ethnicity or sexual orientation should be regarded as irrelevant. To borrow a quote from Martin Luther King, it is the ‘content of their character’ that matters rather than the degree to which someone shows neurodiversity.

The second approach is quite different. This is not enough, it says. Having a positive and accepting attitude still does not allow someone with, for example, ADHD to succeed in an education system which does not recognise or understand the needs associated with their condition. Rather than underplaying the differences displayed by a neurodivergent individual, this approach advocates a need to fully recognise them. Unlike ethnicity or sexual orientation, it argues, neurodiversity does actually affect the way you interact with other people, how you respond to education programmes, employment roles and social situations more generally, and it is not something the individual concerned can voluntarily alter. Society, therefore, needs to adapt to accommodate these differences, and perhaps even to judge performance by a different yardstick from the one used for neurotypical individuals. According to this approach, we cannot simply be blind to these differences, as the first approach would suggest, seeing through them to the ‘normal’ human being inside. We need to recognise that being neurodivergent is part of an individual’s core identity.

The problem with this is that it leads to the medicalisation of conditions through the creation of artificial categories. Where do we draw the line between someone who could be described as neurotypical but nevertheless shows features of a recognised neurodivergent condition, and someone who only just meets the criteria for that condition? It seems a little arbitrary. Surely all human beings sit somewhere on a complex spectrum rather than in neatly defined categories. Is it fair to give special consideration to those just inside the category but not to those who fall just outside it? Read more »

Like many other video gamers (nearly eight million, in fact), I have spent no small portion of recent weeks in the robot-infested, post-diluvian wastes of late-22nd-Century Italy, looting remnants of a collapsed civilization while hoping that a fellow gamer won’t sneak up and murder me for the scraps in my pockets. This has been much more fun than the preceding description might lead you to believe, if you are not a fan of such grim fantasy playgrounds. It has also, interestingly, afforded rather heart-warming displays of the better side of human nature, despite the occasional predatory ambush or perfidious betrayal. It helps somewhat that nobody really dies in this game; they just get “downed” and then “knocked out” if not revived in time, leaving behind whatever gear they were carrying (except for what they were able to hide in their “safe pocket”, the technical and anatomical details of which are left to the player’s imagination).

Like many other video gamers (nearly eight million, in fact), I have spent no small portion of recent weeks in the robot-infested, post-diluvian wastes of late-22nd-Century Italy, looting remnants of a collapsed civilization while hoping that a fellow gamer won’t sneak up and murder me for the scraps in my pockets. This has been much more fun than the preceding description might lead you to believe, if you are not a fan of such grim fantasy playgrounds. It has also, interestingly, afforded rather heart-warming displays of the better side of human nature, despite the occasional predatory ambush or perfidious betrayal. It helps somewhat that nobody really dies in this game; they just get “downed” and then “knocked out” if not revived in time, leaving behind whatever gear they were carrying (except for what they were able to hide in their “safe pocket”, the technical and anatomical details of which are left to the player’s imagination). Chiharu Shiota. Infinite Memory, 2025.

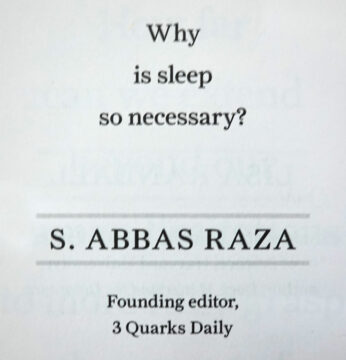

Chiharu Shiota. Infinite Memory, 2025. S. Abbas Raza: You may have heard of

S. Abbas Raza: You may have heard of

Preparing a worksheet with negative-number calculations where all the digits are sixes and sevens. Telling myself it’s meant to take the fun out of it for them – like a sex ed teacher having their students say ‘penis’ one hundred times before starting the unit. Definitely not the whole story, but plausible: as a middle school math teacher I am more than justified in trying to tame the phenomenon. In fact, I have drawn a firm line; just seeing a 6 anywhere in an exercise is decidedly not an appropriate reason for doing the meme. Really, we need to get on with the lesson now; I will count to five.

Preparing a worksheet with negative-number calculations where all the digits are sixes and sevens. Telling myself it’s meant to take the fun out of it for them – like a sex ed teacher having their students say ‘penis’ one hundred times before starting the unit. Definitely not the whole story, but plausible: as a middle school math teacher I am more than justified in trying to tame the phenomenon. In fact, I have drawn a firm line; just seeing a 6 anywhere in an exercise is decidedly not an appropriate reason for doing the meme. Really, we need to get on with the lesson now; I will count to five. Antonio Gramsci’s theory of hegemony helps explain how the power structure of modern liberal-democratic societies maintains authority without relying on overt force. Many definitions of hegemony point out that it creates “common sense,” the assumptions a society accepts as natural and right.

Antonio Gramsci’s theory of hegemony helps explain how the power structure of modern liberal-democratic societies maintains authority without relying on overt force. Many definitions of hegemony point out that it creates “common sense,” the assumptions a society accepts as natural and right.

Art is dangerous. It’s time people remembered that and recognized the fullness of it. For if art is to remain important or even relevant in the current moment, then it’s long past time artists stopped flashing dull claws and pretending they had what it takes to slice through ignorance. We need them swallow their feel-good clichés and to begin sharpening their blades. We need dangerous art, and we cannot afford much more art that its creators believe is dangerous when it is not.

Art is dangerous. It’s time people remembered that and recognized the fullness of it. For if art is to remain important or even relevant in the current moment, then it’s long past time artists stopped flashing dull claws and pretending they had what it takes to slice through ignorance. We need them swallow their feel-good clichés and to begin sharpening their blades. We need dangerous art, and we cannot afford much more art that its creators believe is dangerous when it is not. Emma Wilkins’ excellent piece “

Emma Wilkins’ excellent piece “