by Akim Reinhardt

Art is dangerous. It’s time people remembered that and recognized the fullness of it. For if art is to remain important or even relevant in the current moment, then it’s long past time artists stopped flashing dull claws and pretending they had what it takes to slice through ignorance. We need them swallow their feel-good clichés and to begin sharpening their blades. We need dangerous art, and we cannot afford much more art that its creators believe is dangerous when it is not.

Art is dangerous. It’s time people remembered that and recognized the fullness of it. For if art is to remain important or even relevant in the current moment, then it’s long past time artists stopped flashing dull claws and pretending they had what it takes to slice through ignorance. We need them swallow their feel-good clichés and to begin sharpening their blades. We need dangerous art, and we cannot afford much more art that its creators believe is dangerous when it is not.

When people say Art is dangerous, they’re often bragging. Talking it up like a super hero. Evil had better beware: Art is here to save the day!

Oh my, she gasped, clutching her pearls. Why, how could art possibly do that?

Because it’s dangerous! It reveals the evil that masked villains seek to hide!

Such sentiments are naive. They are wishful thinking. And those sentiments are actually far more dangerous than the art typically produced by those who espouse such sentimets. Supposedly dangerous art often does little more than preach to the choir or wrap important points up in obfuscations that most audiences lack the inclination or even the background to unravel. Instead of puncturing sacred cows or shining a bright light on dark evils, much “dangerous” art merely creates illusions of damage amid billows of self-congratulation and self-satisfaction. When the smoke clears, all the same problems remain, and no one, save for perhaps professionals and other insiders of various art worlds, are any more enlightened, while the problems that had been targeted with “dangerous” art quietly and stubbornly linger.

There are many reasons why art intended to be dangerous ends up being so harmless. Myopia, naivete, and the harmonious allure of echo chambers can derail much. It’s a shame, because art, in any medium, can be dangerous. And right now we need dangerous art very much amid rising authoritarianism. Dangerous art has the capacity to unsettle society and inspire people to resist and move forward. But to intentionally create dangerous art (as opposed to stumbling into it) requires a good understanding of danger, and the courage to face the cacophonous reaction that often follows its release into the world.

Dangerous art is not a sniper rifle. A long range rifle, in the hands of a trained marksman, is dangerous only to the people and animals on the other end of the scope, the targets within a tight circle of cross-haired glass. But art is not dangerous in just one direction. Art’s range is scatter blast and its effects are unpredictable. Dangerous art is not dangerous in just one way; it is dangerous in every way. It can proffer any and all messages, which is dangerous. And those messages, through even the lightest artistic veiling, can be misunderstood in any and all ways, which is also dangerous.

Art can appeal to the best. It can appeal to the worst. And perhaps most dangerous of all, its appeal can be quite different from, even the opposite of, its creator’s intent.

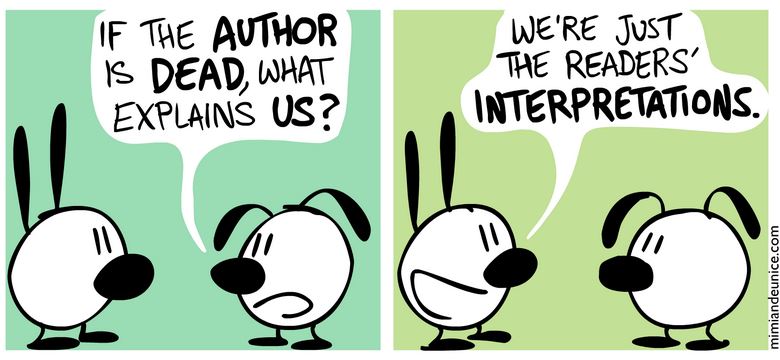

Art is dangerous because the author is dead. While Roland Barthes did not coin that phrase until 1967, the death of authorial authority over artistic works long predates the recognition of it by intellectuals. In some ways the author has always been dead. Just look at Jesus.

It doesn’t matter if Jesus actually said (authored) much of what the New Testament claims he said; personally, I doubt he did. But either way, there is a text, wherein the authors (Matthew, Mark, Luke, John, etc.) artfully attributed posthumous words to him, reconstructing the Christ’s actions, monologs and dialogues. Whatever else it might be, the New Testament is a multi-authored piece of art, and a very dangerous one, history tells us. The effects of this art have gone very far beyond anything its authors could have ever imagined. Their original intentions have been interpreted and reinterpreted so much and so ofte as to leave us wondering, at least to some degree, what those intentions actually were, leading to endless debates. AI tells me (speaking of dead authors) there are about 45,000 different Christian denominations.

It doesn’t matter if Jesus actually said (authored) much of what the New Testament claims he said; personally, I doubt he did. But either way, there is a text, wherein the authors (Matthew, Mark, Luke, John, etc.) artfully attributed posthumous words to him, reconstructing the Christ’s actions, monologs and dialogues. Whatever else it might be, the New Testament is a multi-authored piece of art, and a very dangerous one, history tells us. The effects of this art have gone very far beyond anything its authors could have ever imagined. Their original intentions have been interpreted and reinterpreted so much and so ofte as to leave us wondering, at least to some degree, what those intentions actually were, leading to endless debates. AI tells me (speaking of dead authors) there are about 45,000 different Christian denominations.

Whatever the intentions of the New Testament’s authors, it has been very clear for nearly two millennia now that people are going to read and/or listen to the words of Jesus, claim some form of audience ownership over them, and interpret them in their own ways. If there’s ever been an example of the author’s intentions not being the primary focus of the readers’ interpretations, but rather the authored work becoming independent of its creator and open to various interpretations based on readers’ experiences, interpretative abilities, and desires, well, this is it. Even self-professed literalists who claim adherence to only the words, not interpretations of them (if such a thing is even possible), cherry pick the sayings and narratives of Jesus and other biblical figure that they wish to emphasize so as to promote their preferred religious agenda.

You may choose to not consider religious documents, particularly if they are of your religion, as art. I view all religious stories and proverbs through an artistic lens (among others), not because as an atheist I see them as fictitious, but because, like art, religious documents are open to interpretation. Art is much more than just subjectivity, and not everything open to interpretation (which is almost everything) strikes me as particularly artful. However, the absence of the artistic is the crystal clear messaging of pure didacticism. While art can be literary, the non-artistic is literal. It is what it is. Done. And there are certainly times and places for the purely didactic: most of our lifetimes and most places upon the Earth. In general, we humans strive to articulate our thoughts as clearly as we can and hope to have them understood as accurately as possible. To not be artistic. Clear, literal communication can, at times, be done artistically, but that is already taking a gamble; perhaps the artistry will obscure meaning to some people, or perhaps some people will receive the message but miss the artistry. Once you add artistic elements, you are adding a veil that, whether slightly or radically, obscures literal meaning.

This is why Lenhi Riefenstal’s Triumph of Will, and especially her film Olympia, were/are so dangerous. The films’ artistic veiling opens, and even encourages, the possibility that viewers who would otherwise be hostile to Nazism will receive its pro-Nazi messaging warmly because viewers fail to fully recognize its pro-Nazi messaging as such. Without the artistry, the films would be straight propaganda, the didactic promotion of Nazi values and dogma. But with artistic veiling, the films’ pro-Nazi messaging have the potential to become seductively obscured and attractive in ways it would not otherwise be.

The inverse of this would be an artistic critique of human horror, with the artistic veiling leading the audience to misinterpret the art as being the actual horror, confusing the critic for the subject. An example would be taking satirical literature literally, perhaps believing that Jonathan Swift really was advocating economic reform and population control through the slaughter and eating of poor Irish children as outlined in his 1728 satirical pamphlet A Modest Proposal for Preventing the Children of Poor People from Being a Burthen to Their Parents or Country, and for Making Them Beneficial to the Publick.

Artists often intend to elicit a certain reaction, but there are no advanced guarantees about which reactions their art will actually elicit from whom. Therein lies the danger. But if such risks are minimized, if the art is composed as safely (ie. didactically) as possible, the resulting art will increase its chances of finding its intended target. This might conform to the artist’s goal, but it makes the art safer, less dangerous. And right now we need dangerous art.

We need art that will make people think about things they did not intend to think about, and to think about them in ways they did not anticipate, in ways they have not thought about them before. Dangerous art calls upon us to be smarter without sitting us down for a lesson. Freed from the artist’s corral, art leaps and runs free. It surprises us. Who will get smarter? How will they get smarter? Is it you? Is it your ally? Is it your enemy? Will your enemy get smarter in ways that lead them to agree with you more? Will you get smarter in ways that lead you to agree with them more? “Both sides” arguments can be very stupid when done in shallow ways. But genuine empathy and insight are dangerous because you can’t anticipate who will learn what, how anyone will change, and who will hate whom less or more.

Dangerous times call for dangerous art. Release the hounds

Akim Reinhardt’s website is ThePublicProfessor.com