by Mark R. DeLong

“People tell me that I could do much better,” David McCullough said in an interview included in California Typewriter, a documentary about typewriters “and the people who love them.” “I could go faster and have less to contend with if I were to use a computer—a word processor—but I don’t want to go faster. If anything, I would prefer to go slower.” He liked the straightforward mechanism of his Royal Standard Typewriter that he bought, used, in 1965 for about twenty-five dollars. “To me, it’s understandable: I press the key and another key comes up and prints a letter on a piece of paper and then you can pull it out. It’s a piece of paper upon which you have printed something.

“You’ve made that. It’s tangible. It’s real.”

That tangible quality, that reality comes clear in Richard Polt‘s Typewriter Manifesto, which concludes with a series of contrasts of typewriter life and digital life (using the red and black colors of some typewriter ribbons):

We choose the real over the representation,

the physical over the digital,

the durable over the unsustainable,

the self-sufficient over the efficient.

And then the manifesto concludes, “THE REVOLUTION WILL BE TYPEWRITTEN” of course.

Keyboards are keyboards, you might say. It’s the fancy stuff behind them that matters. Typewriters also have had their incremental improvements, electrification being the most obvious and, less obvious perhaps, the improvements on font rendering. The old fashioned levered hammer bearing the inverse shape of letters gave way to ingenious “balls” as in the IBM Selectric and “printwheels” that look like a miniature, heavy-duty bicycle wheel with spokes that bear the letters. (My own old typewriter has this technology.) These innovation allowed for font changes and vastly improved print typesetting. That story about the ingenious QWERTY keyboard layout minimizing key jambs and speeding production of words? I’d say, probably false. A more likely reason for that innovation was probably a simple marketing trick: a salesman who didn’t know how to type could still peck out T-Y-P-E-W-R-I-T-E-R using only the letters on the top row.

Like the inventions of user-friendly handwriting, such as the famous “Palmer Method” of script, the invention of the typewriter was built for business. It is “an almost sentient machine,” a New York newspaper reporter put it. Its impact “has been so complete, so overwhelming and withal so rapid that we who stand in the midst of it cannot properly realize its full import.” Reading that statement, I’m tempted to think that the “almost sentient machine” is the computer, probably a networked personal computer, though the prose seems a bit more formal than what you’d read in the New York Times today. But the machine was a typewriter. The words were printed in the New York Daily Tribune back in 1901. A decade-and-a-half before that Tribune story, the Salt Lake Herald had pointed out the clear use case for typewriters in business. It vastly increased productivity in the office: “An office boy, for instance, with but two month[s] practice on one of these machines can accomplish more work than two rapid penmen; besides do it in a neater, and more attractive and legible manner. With but little more practice he can perform more than three men’s work.”

Typewriters were simply tools for businesses and continued to be so for writers of a certain age. In general, they increased the writers’ strength—a pliers for the letter trade, in a manner of speaking. The typewriter stayed clear of the human process of writing, or at least much of it. It didn’t “suggest” or “correct”; lucky writers had good editors to help with that, usually through an annoyingly human interaction. (I have also found that my word processing software’s autocorrect has only automated the annoyance without any of the restorative salve of human interaction—with the effect of actually increasing the annoyance … automatically.)

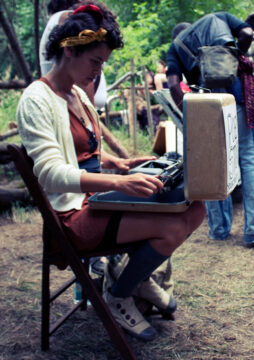

Today, of course, typewriters have been escorted out of the office, at least for the most part. But they have been welcomed by poets and writers. “Typewriter poets” offer spontaneous versification on sidewalks and at receptions and events. Down the road from my house, a typewriter poet named Poetry Fox regularly produces on-demand poetry in the city; he wears a fox costume as he plunks out poetry on a vintage typewriter.1Poetry Fox (aka Chris Vitiello) was at “Spa Day” when Nina Riggs had an appointment with her oncology team at Duke Cancer Center. “A FOX WROTE US A POEM! ON A TYPEWRITER! BETWEEN ONCOLOGY APPOINTMENTS!” she wrote in her blog. Riggs’ bestselling memoir The Bright Hour: A Memoir of Living and Dying recounts the story. She died in 2017, months before her book appeared. She was 39 years old. There are typewriter poets everywhere, it seems, and the machine itself has a certain artistic aura, oddly enough.

Richard Polt suggests a reason in The Typewriter Revolution: A Typist’s Companion for the 21st Century (2015): “Online social media promise to provide human connections. And they do—but the connections are filtered, skewed, and spread thin. Beyond a certain level, sharing isn’t care. Put a typewriter in front of people and they’ll want to write from within. The typewriter doesn’t push ‘content’ at them; it draws words from them.”

That curious drawing power might be the result of the contrast of typewriter machinery with the machinery of the whole algorithmic world that now surrounds it; that is, the power isn’t emanating from the machine itself, by itself. The typewriter charms in some ways that it couldn’t before, back when it was the norm of writing for sharing or for business. That ancient lump of metal in your attic has been preserved in dust, but its meaning has changed because of the new emerging context surrounding it. The modes and expectations of text have shifted. As a result, the old typewriter’s renewed clattering of letters comes strangely into the world.

Today, the typewriter does new and different stuff without being physically different from what it was decades ago.

“The kids get it,” Paul Lundy says. “They’re not trying to be nostalgic for something they never experienced. They’re trying to escape what they experience every day.” Lundy, owner of the Bremerton Typewriter Company, was profiled in a recent New York Times story, tellingly entitled “How to Fix a Typewriter and Your Life.” It is one of many articles that have cropped up in the past decade or so, ever since social media edged out the slow pleasures of reading and writing.

But the “kids” who use Old Skool Smith Coronas, IBM Selectrics, Royal Standards, or Remingtons are not mere escapists, either, at least after they crank out a few school papers. They are practitioners and discoverers of old tools—if not re-creators of tools—teasing out the strengths of their human creativity as they master the mechanical until … until the mechanical allows them to transmute their human strengths into new expression. The typewriter is not magical, but its clattering beat can give voice to new sounds. The old machine’s pace, once a marvel of productivity-enhancing speed, establishes a cadence and rhythm that some find useful, even pleasurable.

While once I cursed when I made a typo—especially in the last couple of lines of a more-or-less well typed page—and had to grab my Liquid Paper to blot out the sin, today the X’ed out letter or the blob of obscuring paper paint points to a fallible human. It’s not a big deal and may be even a bonus. Today’s typewritten error, visibly corrected, somehow endears. It’s worth noting how the cutesy modern electronic notion of “striking out” words itself conveys a fuckingly drastically different meaning. “Striking out” a word has achieved a rhetorical meaning on the digital display. Rather than obscuring or begging the poor slug who is doomscrolling reader to disregard a word or error, the “strikeout” intensifies readers’ attention. The struck out word often is the word that is actually meant—partially obscured only because it seems too damned impertinent or too cringe honest or, paradoxically, it’s a modern word-processing writer’s actually preferred and usually blunt word choice.

The electronic “strikeout” is an ironically flavored italic; it accentuates with attitude. Old fashioned typewriters with their X’ed out words messily beg forgiveness for error and politely hide it, too. “X’ing out” with real overstricken X’s is, unhappily, not a feature included with Microsoft Word.

Not your grandfather’s typewriter?

Austin Kleon has done a series of “typewriter interviews” (I suspect he may have even coined the phrase) that leverage a new set of typewriter-borne powers of expression and its new set of charms. It actually may have been an accidental discovery; in his first typewriter interview, Kleon mentions that Mary Ruefle “doesn’t do Zoom interviews or use a computer, so we conducted this interview via our typewriters. I typed a bunch of questions on individual pieces of yellow paper and mailed them to her home in Bennington, Vermont. She typed her answers underneath and mailed them back to me.” The yellow paper looks suspiciously like Post-It notes, which would be a useful thing to use. He might have had them on hand, typed up his questions at the top of each slip of paper, sent them, and then—when they returned in US Post—realized that the form itself was striking. (Or maybe, since he is after all Austin Kleon, he hatched the whole plan knowing what would come of it.)

In Kleon’s hands, the typewriter turns into a new form of paintbrush; he uses it to create images—visual evidence of human interaction—and it functions because it is contrary to the formal expectations we readers of screens have internalized. The yellow sheets have a question cramped into the top of the slip that’s separated by a line of hyphens. Left margins are often just irregular. No neat lines. Typos get the XXXX treatment. The form of the typewritten note carries human qualities; you know that flesh-and-blood was behind the words. Typos and crossouts transform from error to light amusement, and the underlying technologies are fairly primitive. “This interview was conducted via our typewriters and the United States Postal Service,” Kleon tells us in the introduction of his typewriter interview with Kelli Anderson which is, I think, among the best, since Anderson plays with her typewriter as an image-making device.2Though Lynda Berry writes by hand IN CAPITAL LETTERS, mostly. In response to Kleon’s question “What is it about dogs? Should I get one?” she also scribbles a picture of a dog bearing a sign that says, “DO YOU LIKE THE WAY THEY SMELL? IF SO, YES!” Liana Finck likewise handwrites IN CAPITAL LETTERS, peppering her prose with drawings. “I’M VISUAL ALL THE WAY,” she writes. Kate Bingaman-Burt handwrites, too, and she has a wonderful and very distinctive hand. (She’s an illustrator by profession.) All of Austin Kleon’s typewriter interviews are here: https://austinkleon.substack.com/t/typewriter-interviews

Kleon’s use of the typewriter in this way is not be entirely new—such slow typewriter-mediated interviews have been around for some time—but in a world of uniform design of web pages and standardized electronic fonts and graphics (not to mention the pablum-like slop of AI), the human mess of typewritten notes represents a new authenticity. A physical reality we humans know quite well from the messiness of our lives—and a reality that the boringly normalized gleam of computer screens tries to scrub away.

I try to put my finger on the charm of a typewriter interview, and I can only come up with the fact that the form somehow illumines human immediacy: the words are mechanically rough-hewn and often eloquent and energetic, the typography suggests an ease of speech, almost a banter, and its errors bring the interlocutors together. It’s okay to err and be “off-the-cuff” here, the typewritten text implies, we’re humans chatting in a “new” way, clattering along our ancient keyboards with hammered letters from dies that—come to think of it—might need a good cleaning.

Kleon has reclaimed the typewriter (or at least its graphical mode) as a tool of writing, magnifying a force for writers by running contrary to the slick and (mostly) error-free typefaces of processed text, Microsoft Word docs, and PDFs. But most of the power of Kleon’s typewriter interviews, unsurprisingly enough, is that fact that they look like typewritten exchanges.3A quick comparison of two of the interviews Kleon has conducted reveals the results of the typewriter’s presence in the “interview.” His typewriter interview with Kelli Anderson was totally typewriter-driven, and Anderson played with the typewritten responses, even creating images with symbol keys. Kleon shares the completed slips of paper in his post. The other interview was in some sense “half-typewritten.” It was Kleon’s interview with Sally Mann. Kleon reported, “She got rid of her Olivetti years ago, so she answered my snail mail questions via email from her home near Lexington, Virginia.” While Mann’s responses are delightful, they are often much longer than the responses that are limited by the boundaries of the yellow slips of paper in other interviews. They do have a format, and they enforce brevity: there just isn’t much room to type on. Some interviewees squeeze inked words in small blank corners or fix words with a pen.

Typewritten formats can renew playing with conventions

The typewriter interview re-expresses a tradition that is ancient and that has reasserted itself for centuries and that, in fact, has become so much a part of readers’ experience that it is obscured by familiarity. We readers abide by nearly invisible conventions of text; unconventional manipulations of text—as with Kleon’s typewriter interviews—open up new means of expression, some of which are truly show-offs on the page.

![On quite old brown paper, a human shape composed of serif typefaces--a poem from Apollinaire. The type creates a human shape, arms extended and legs spread in a "spread-eagle" shape. The poem may read "aMANTS COUCHÉS ENSEMBLE VOUS VOUS SÉPAREREZ [sic] MES MEMBRES"](https://3quarksdaily.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/apolloniaire-1918-amants-detail-274x360.jpg)

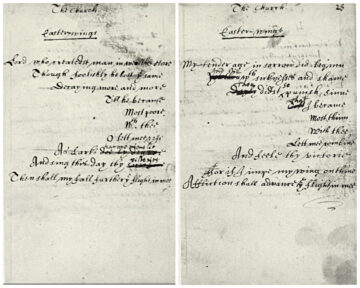

The play of imagery and text—and text as imagery—wasn’t Apollinaire’s invention either. It goes back centuries, and in his case might have been inspired by Chinese ideograms. “Concrete poetry” had already pictorially embodied some of the meanings of a poem’s words. Two centuries before Apollinaire’s Calligrammes was posthumously published, English poet and priest George Herbert had mastered the form, and in my mind, its most memorable expression is “Easter Wings” (originally published sideways) which compresses the Fall and resurrection into two stanzas, both ordered and shaped into flying wings, the first relating generally to humankind and the second, more personally. The tying constraints of sin and then freedom of salvation show up even in the line lengths. And as a result the whole thing flies.

Shaping words to image goes back much farther than the English Renaissance. The British Museum holds the Harley MS 2506, part of which is Cicero’s translation of Aratus’ Phenomena. In it, Cicero’s translations are rendered into text in the shape of the mythological characters of constellations. That manuscript dates back to the ninth century.

But the force that particularly adds to the form of Austin Kleon’s typewriter interview is subtler, internalized in readers and writers and therefore less obvious—part of very familiar (and therefore practically invisible) landscape of literacy. In her interview with Kleon, Kelli Anderson points to Johanna Drucker as one of her artistic forebears, and Drucker’s work unpacks assumptions and embedded meanings of typesetting. That is, typesetting as a form and guide of book page-layout. Drucker’s Diagrammatic Writing (2013) explicates the effects of page layout, type sizes, and text placement, showing the ways that these common elements calibrate readers’ responses, even their emotions. When I looked through the work, I wondered whether the effects that her work elicits are the products of some internalized conventions or whether they are parts of the way that human consciousness works. (I’m leaning toward convention, by the way).

Drucker’s work suggests to me that the playful and carefree qualities that I see in Austin Kleon’s typewriter interviews are artistic in the sense that they break the vessels, so to speak, of conventional cultural assumptions about, well, interviews, for one, and the forms of media that contain them. Kleon captures a new expressive medium in small and delightful parcels, and the delight in part comes from watching two people break the rules of the old traditional game of interviewing—a game of media conventions like those Johanna Drucker revealed.

I mentioned that Austin Kleon didn’t invent the typewriter interview. I’ve made my very own contribution to the form.

In 1978, when my then girlfriend and I were in Duluth Typewriter searching for a cheap used typewriter, I conducted my own typewriter interview, which has had a profound influence on my life.

I tested out an old mechanical typewriter:

Will you marry me?

She, looking on, let my fingers drop from the keys and then typed:

YES

It was a very successful interview.

For the bibliographically curious: From 1901, an early history of the typewriter: “The Art Preservative,”New-York Daily Tribune (New York [N.Y.]), January 6, 1901, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA (LOC control number: sn83030214); https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn83030214/1901-01-06/ed-1/. Cameron Knight did his own “typewriter interview” with Richard Polt in early 2023: Cameron Knight, “Inside the World of Typewriters and the Niche Hold They Have on the Modern World,” The Enquirer, April 26, 2023, https://www.cincinnati.com/in-depth/news/2023/04/26/vintage-typewriters-collector-richard-polt-cincinnati/69704726007/. From Richard Polt, too: “TYPEWRITER REVOLUTION // Resist the Paradigm // 100% Human Made,” Typewriter Revolution, https://typewriterrevolution.com/. Jillian Freyer and Scott Cacciola, “A Type-In to Say Goodbye to a New England Institution,” Style section, The New York Times, March 24, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/card/2025/03/24/style/cambridge-typewriter-company-party. David W. Dunlap, “A Typewriter That Has Traveled the World,” Times Insider, The New York Times, November 23, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/11/23/insider/olivetti-lettera-typewriter.html. Eric Lacitis, “Typewriter Repairman, 94, Finds Apprentice to Buy Bremerton Shop,” The Seattle Times, April 29, 2016, https://www.seattletimes.com/business/local-business/areas-last-typewriter-repair-shop-to-go-on-clicking/. A delightful documentary (skip the ads): California Typewriter – Tom Hanks & The People Who Love Typewriters, produced by John Benet and Doug Nichol, directed by Doug Nichol, 2022, YouTube video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AWfgpL1X_oE. Touching entry from Nina Riggs blog: Nina Riggs, “The Poetry Fox (and Other Tales from the Cancer Center).,” Suspicious Country, June 4, 2015, https://suspiciouscountry.wordpress.com/2015/06/04/the-poetry-fox-and-other-tales-from-the-cancer-center/. The Library of Congress is a treasure. I hope the Trump Administration doesn’t completely screw it up: Ellen Terrell, “The Typewriter – ‘That Almost Sentient Mechanism,’” The Library of Congress, March 19, 2015, https://blogs.loc.gov/inside_adams/2015/03/the-typewriter-that-almost-sentient-mechanism. Guillaume Apollinaire, Calligrammes; poèmes de la paix et da la guerre, 1913-1916 .., (Mercvre de France, 1918), http://archive.org/details/calligrammespo00apol.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Footnotes

- 1Poetry Fox (aka Chris Vitiello) was at “Spa Day” when Nina Riggs had an appointment with her oncology team at Duke Cancer Center. “A FOX WROTE US A POEM! ON A TYPEWRITER! BETWEEN ONCOLOGY APPOINTMENTS!” she wrote in her blog. Riggs’ bestselling memoir The Bright Hour: A Memoir of Living and Dying recounts the story. She died in 2017, months before her book appeared. She was 39 years old.

- 2Though Lynda Berry writes by hand IN CAPITAL LETTERS, mostly. In response to Kleon’s question “What is it about dogs? Should I get one?” she also scribbles a picture of a dog bearing a sign that says, “DO YOU LIKE THE WAY THEY SMELL? IF SO, YES!” Liana Finck likewise handwrites IN CAPITAL LETTERS, peppering her prose with drawings. “I’M VISUAL ALL THE WAY,” she writes. Kate Bingaman-Burt handwrites, too, and she has a wonderful and very distinctive hand. (She’s an illustrator by profession.) All of Austin Kleon’s typewriter interviews are here: https://austinkleon.substack.com/t/typewriter-interviews

- 3A quick comparison of two of the interviews Kleon has conducted reveals the results of the typewriter’s presence in the “interview.” His typewriter interview with Kelli Anderson was totally typewriter-driven, and Anderson played with the typewritten responses, even creating images with symbol keys. Kleon shares the completed slips of paper in his post. The other interview was in some sense “half-typewritten.” It was Kleon’s interview with Sally Mann. Kleon reported, “She got rid of her Olivetti years ago, so she answered my snail mail questions via email from her home near Lexington, Virginia.” While Mann’s responses are delightful, they are often much longer than the responses that are limited by the boundaries of the yellow slips of paper in other interviews.