A glass ashtray turned the weak winter sunlight from the window into this rainbow on a wooden cutting board on our kitchen counter.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

A glass ashtray turned the weak winter sunlight from the window into this rainbow on a wooden cutting board on our kitchen counter.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

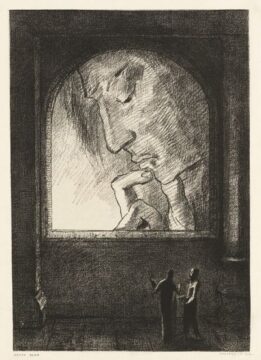

by Katalin Balog

In a recent bestseller, Eliezer Yudkowsky and Nate Soares argue that artificial superintelligence (ASI), if it is ever built, will wipe out humanity. Unsurprisingly, this idea has gotten a lot of attention. People want to know if humanity has finally gotten around to producing an accurate prophecy of impending doom. The argument is based on an ASI that pursues its goals without limit—no satiation, no rest, no stepping back to ask what for? It seems like a creature out of an ancient myth. But it might be real. I will consider ASI in the light of two stories about the ancient king Midas of Phrygia. But first, let’s see the argument.

What is an ASI?

An ASI is supposed to be a machine that can perform all human cognitive tasks better than humans. The usual understanding of this leaves out a vast swath of “cognitive tasks” that we humans perform: think of experiencing the world in all its glory and misery. Reflecting on this experience, attending to it, appreciating it, and expressing it are some of our most important “cognitive tasks”. These are not likely, to use an understatement, to be found in an AI. Not just because AI consciousness is rather implausible to ever emerge, but also because, even if AI were to become conscious, it would not do these things, not if its developers stuck to the goal of creating helpful assistants for humans. They are designed to be our servants, not autonomous agents who resonate with and appreciate the world.

OK, but what about other, more purely intellectual tasks? LLMs are already very competent in text generation, math, and scientific reasoning, as well as many other areas. While doing all those things, LLMs also behave as if they are following goals. So are they similar to us, after all, in that they know many things and are able to work toward goals in the world? Read more »

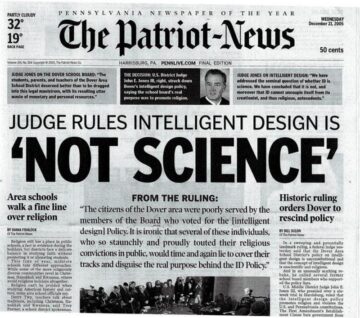

by Paul Braterman

Last Saturday was the 20th anniversary of the day on which Judge John Jones III handed down his decisive ruling, in the case of Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District, that Intelligent Design was a version of creationism, which is religion and not science, and as such violated the Establishment Clause of the US Constitution and could not be taught within the publicly funded school system. Given changes in the US legal landscape, we need to ask whether this ruling is still secure. And given everything else that is happening in the US at the moment, we may wonder whether this even matters. Here I lay out why I think that the ruling is not necessarily secure, review what is at stake, and argue that it matters very much indeed.

Last Saturday was the 20th anniversary of the day on which Judge John Jones III handed down his decisive ruling, in the case of Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District, that Intelligent Design was a version of creationism, which is religion and not science, and as such violated the Establishment Clause of the US Constitution and could not be taught within the publicly funded school system. Given changes in the US legal landscape, we need to ask whether this ruling is still secure. And given everything else that is happening in the US at the moment, we may wonder whether this even matters. Here I lay out why I think that the ruling is not necessarily secure, review what is at stake, and argue that it matters very much indeed.

What we now call Christian Nationalism has its roots in Ronald Reagan’s 1980 presidential campaign, when creationists such as Tim LaHaye fused together political conservatism, the newly adopted abortion issue, literalist Bible-based religion, and the rejection of evolution science as Humanist, un-American, and as we would now say Woke. We can see the influence of these ideas today in Trump’s administration, where at least three cabinet ministers (Pete Hegseth, Scott Turner at HUD, and Doug Collins at the VA) are creationists, as are Speaker Mike Johnson, Mike Huckabee, ambassador to Israel, and Russell Vought who at the Office of Management and Budget has enormous day-to-day influence. To these we might add Vice President Vance, and Health [sic] Secretary RF Kennedy Jr. These are not creationists, but share their disdain for the scientific and academic establishments; Vance rose to stardom by telling the US Religious Right that “the Professors are the enemy,” while Kennedy’s onslaught on established science is all too well-known. Thus creationism is closely coupled to the rest of the Regime’s war on reality.

As for the claim, pervasive in the creationist literature, that evolution acceptance involves religion denial, I should mention here that Judge Jones himself is a committed Lutheran, and has offered himself as an example of the compatibility of Christian belief and evolution acceptance, while Ken Miller, a crucial witness at the trial and indefatigable campaigner against creationism, is a devout Catholic, author of Finding Darwin’s God, and co-author of a widely used high school textbook, Miller and Levine Biology. Read more »

by Tim Sommers

“I’d rather entrust the government to the first 400 people listed in the Boston telephone directory,” William Buckley once said, “than to the faculty of Harvard University.” If we can put aside his right-reactionary politics and look past the performative anti-intellectualism on display here (from a Yalie!), there is the seed of an interesting question here. Could we replace elections with random selections?

A recent mini-movement among political philosophers has answered, yes, we could. Arguably the leader of this movement, Alexander Guerrero, author of Lotacracy: Democracy Without Elections (2024), has gone further arguing we should eliminate voting in favor of a lottery system to appoint our political representatives. Here’s Guerrero describing his view and its advantages.

We would be better off using randomly chosen citizens, selected to serve on single-issue legislatures (each covering, say, transportation or education or agriculture), who would learn about the relevant issues in detail and engage with each other over an extended period of time to make policy decisions. Instead of a generalist legislature like Congress, we would have 30 single-issue legislatures, each with 300 randomly-chosen citizen legislators serving three-year terms. A true random selection of citizens age 18 and up could be established using mechanisms like those used for jury selection. Those selected wouldn’t be required to serve, but a significant salary, the promise to accommodate family and work requirements, and the sense that service is a civic duty and honor should encourage them. Without elections, we would lose the sense that ‘our team’ wins or loses. We wouldn’t have teams in the same way. Moving away from a generalist legislative process opens up places for us to identify issues on which we agree rather than having our attention concentrated on those few issues that most deeply divide us. Without campaign promises, political ads and re-elections, we could finally move beyond the capture and control of political institutions by wealthy corporate interests. This would truly return democratic control to the people.

I am not a huge fan of this view, but I have to say Guerrero deserves a lot of credit for his tightly argued, imaginative work. As John Rawls emphasized in developing his own theory of “justice as fairness,” the best way to evaluate ethical and normative political views is to have well-developed, comprehensive alternatives to compare. Guerrero has certainly developed – across 464 pages – a comprehensive alternative to democracy as currently practiced. Also, props to Guerrero for the bravado involved in even imaging an alternative to conventional democratic politics – especially in such detail.

Lotacracy is not entirely unprecedented. Athens had one. Sort of. Our current jury system can be seen that way. And there have been recent experiments with lotacracy around the world, for example, in Canada. But these lotteries have been been quite limited, deliberative rather than legislative, and advisory only.

Guerrero says he has four main reasons to prefer lotteries to elections. Read more »

by Christopher Hall

“This business of a poet,” said Imlac, “is to examine, not the individual, but the species; to remark general properties and large appearances. He does not number the streaks of the tulip, or describe the different shades of the verdure of the forest. He is to exhibit in his portraits of nature such prominent and striking features as recall the original to every mind, and must neglect the minuter discriminations, which one may have remarked and another have neglected, for those characteristics which are alike obvious to vigilance and carelessness.” —Johnson, Rasselas

If poets are to take Imlac’s advice – and I’m not necessarily sure they should – then the proper season for doing so must be winter. No streaks of the tulip to distract us, and the verdure of the forest has been restricted to a very limited palette. Then the snow comes, and the world becomes a suggestion of something hidden, accessible only to memory or anticipation, like a toy under wrapping. Perhaps “general properties and large appearances” are accessible to us only as we gradually delete the details of life; we certainly don’t seem to have much access to them directly. This is knowledge by negation; winter is the supreme season for apophatic thinking.

If poets are to take Imlac’s advice – and I’m not necessarily sure they should – then the proper season for doing so must be winter. No streaks of the tulip to distract us, and the verdure of the forest has been restricted to a very limited palette. Then the snow comes, and the world becomes a suggestion of something hidden, accessible only to memory or anticipation, like a toy under wrapping. Perhaps “general properties and large appearances” are accessible to us only as we gradually delete the details of life; we certainly don’t seem to have much access to them directly. This is knowledge by negation; winter is the supreme season for apophatic thinking.

In the poems I’m going to look at here, when snow comes, it often comes precisely as this kind of obliterator of detail, but it would be difficult to consistently see a restorative counter-movement toward the “knowledge of nature” and “modes of life,” as Imlac says later. Sometimes negation is only that, and loss is loss. Robert Penn Warren’s “Love Recognized” opens with deadening repetition and lack of precision:

There are many things in the world and you

Are one of them. Many things keep happening and

You are one of them, and the happening that

Is you keeps falling like snow

On the landscape of not-you, hiding hideousness, until

The streets and the world of wrath are choked with snow.

“Many things in the world,” “Many things keep happening” – the stammering opening is in the language of someone not sure how to articulate something, hoping that simply by rearranging the same words and making a few minor additions some meaning may be aimed at. The division made here between self and world is the simplest possible: “you” verses “not-you.” But at least the snow comes to hide “hideousness” and the “world of wrath.” Read more »

Sughra Raza. Underbelly Color and Shadows. Santiago, Chile, Nov, 2017.

Sughra Raza. Underbelly Color and Shadows. Santiago, Chile, Nov, 2017.

Digital photograph.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Sherman J. Clark

There is no other way of guarding oneself from flatterers except letting men understand that to tell you the truth does not offend you. —Machiavelli

A friend recently described to me his research in quantum physics. Later, curious to understand better, I asked ChatGPT to explain the concepts. Within minutes, I was feeling remarkably insightful—my follow-up questions seemed penetrating, my grasp of the implications sophisticated. The AI elaborated on my observations with such eloquence that I briefly experienced what I can only describe as Stephen Hawking-adjacent feelings. I am no Stephen Hawking, that’s for sure. But ChatGPT made me feel like it—or at least it seemed to try. Nor am I unique in this experience. The New York Times recently described a man who spent weeks convinced by ChatGPT that he had made a profound mathematical breakthrough. He had not.

To be clear: Chat GPT was very helpful to me as I tried to understand my friend’s work. It explained field equations, wave functions, and measurement problems with admirable clarity. The information was accurate, the explanations illuminating. I am not talking here about AI fabrication or unreliability. And in any event, it does not matter whether a law professor understands quantum physics. The danger wasn’t in what I learned or failed to learn about physics—it was in what I was l was at risk of doing to myself.

Each eloquent elaboration of my amateur observations was training me in the wrong intellectual habits: to confuse fluent discussion with deep understanding, to mistake ChatGPT’s eloquent reframing of my thoughts for genuine insight, to experience satisfaction where I should have felt appropriate humility about the limits of my comprehension. I was nurturing hubris precisely where I needed to develop humility. And, crucially, intellectual sophistication does not guarantee immunity. Anyone who has spent time on a college campus knows that intellectual hubris has always flourished among the highly educated. It is hardly a new phenomenon that cleverness and sophistication can be put to work in service of ego and self-deception.

What makes AI different is that it has become our companion in this self-deception. We are forming relationships with these systems—not metaphorically, but in the practical sense that matters. Read more »

by Lei Wang

Lately I have the feeling that everything is speaking to me. This is concerning, not least because there is a family tendency towards mild schizophrenia. As a delinquent intellectual, I have read only a tablespoon of Jung and have never gone to analysis; in fact, I have resisted treating life like literature. I know that not everything is symbolic, that sometimes things happen for no good reason, or at least not any reason that I can claim to know. And yet recently I have been treating everything as a sign: IF the universe were speaking to me, what would it be trying to say?

And I have also been saying back to the universe, “Hey, I got your message!” When the toilet kept running after a midnight flush, disrupting my sleep, I thought it was trying to tell me I had been inconsiderate of my downstairs neighbor, flushing so late. “Thank you,” I said to the toilet. “I got it. Your job here is done.” And immediately the messenger quieted. Yes, every college student knows: correlation, not causation.

But tell that to my Hyperactive Agency Detection Device: what the neuroscientist Justin Barrett calls the part of our nervous systems that is alert for some kind of intelligence beneath reality, probably because once upon a time it was helpful to think the grass moved not from the wind but from something prowling inside it. The Hyperactive Agency Detection Device (HADD) is liberal with giving away a sense of agency. It’s the mechanism by which we attribute essence and personality to our stuffed animals, even if they’re not “real”; it’s how people have AI boyfriends nowadays. Conspiracy theorists have a lot of HADD.

The other day, procrastinating on writing, I was fixing a beloved broken necklace clasp by transferring a clasp from a different, less beloved necklace (I have not gone so far as to believe my necklaces care about this hierarchy). Anyway—a tricky business, having neither pliers nor delicate fingers. I managed three steps in this way, but in the final step, the tiny lobster clasp flew off the desk. I heard it land on the hardwood floor. I swept; I scoured; I was late to my Zoom. I couldn’t find it anywhere in the world on my hands and knees and yet it was everywhere in my consciousness. For hours. My body, which usually finds many ways to be distracted and get itself snacks, had transformed into pure hunter. Read more »

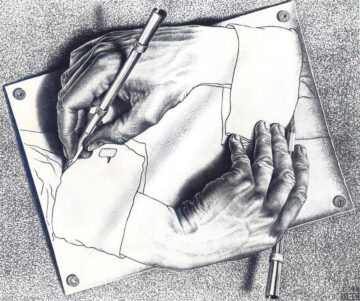

First time I saw Escher’s two hands drawing themselves I thought,

how cool this picture is in its absurd beauty, then much later,

as in now, it comes to me as I give my cognition another chance,

another shot at understanding, more clout in the process of perception,

I think, this is a fundamental truth, a reality truer than the day-to-day

fever dreams of imagination, a truth offering “Eureka!” the word ever followed

by an exclamation point which has just explicitly summed and shattered

the boundary between ignorance and understanding.

There they are, two hands poised with pencils, expressing

the extraordinary, uncomplicated truth that from

cradle to grave we are all drawing shifting renditions

of ourselves.

by Jim Culleny

12/16/25

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

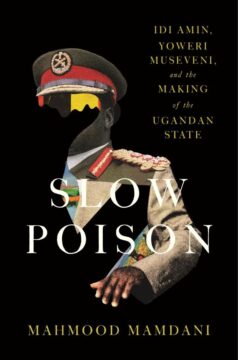

by Azra Raza

In June 1976, an Air France flight from Tel Aviv to Paris was hijacked by members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine along with two German radicals, diverted to Entebbe, Uganda, and received with open support from Idi Amin. There, the hijackers separated the passengers—releasing most non-Jewish travelers while holding Israelis and Jews hostage—and demanded the release of Palestinian prisoners. As the deadline approached, Israeli commandos flew secretly to Entebbe, drove toward the terminal in a motorcade disguised as Idi Amin’s own and stormed the building. In ninety minutes, all hijackers and several Ugandan soldiers were killed, 102 hostages were freed, and three died in the crossfire. The only Israeli soldier lost was the mission commander, Yoni Netanyahu.

In June 1976, an Air France flight from Tel Aviv to Paris was hijacked by members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine along with two German radicals, diverted to Entebbe, Uganda, and received with open support from Idi Amin. There, the hijackers separated the passengers—releasing most non-Jewish travelers while holding Israelis and Jews hostage—and demanded the release of Palestinian prisoners. As the deadline approached, Israeli commandos flew secretly to Entebbe, drove toward the terminal in a motorcade disguised as Idi Amin’s own and stormed the building. In ninety minutes, all hijackers and several Ugandan soldiers were killed, 102 hostages were freed, and three died in the crossfire. The only Israeli soldier lost was the mission commander, Yoni Netanyahu.

Two years later, I traveled to Uganda myself to visit my parents, who were there while my father helped draft the nation’s new constitution for Idi Amin’s regime. I had no idea that this brief stop in Entebbe would return to haunt me decades later—when, in 2003, I was detained for over five hours at Ben Gurion Airport with my nine-year-old daughter, questioned endlessly about why I had ever set foot in Entebbe at all.

While in Uganda, my siblings and I fell instantly in love with the country—the sheer beauty of the land, the dark mystery of Bat Valley with tens of thousands of fruit bats rising in the evenings as a black cloud from the edge of the city near William Street, the riotous, ever-changing foliage that seemed to reinvent itself every few steps, and the magnificent wildlife we encountered in breathtaking abundance on our unforgettable safari. That trip remains one of the best trips of my life filled with the warmest memories of the country and the people.

Years later, as I began to understand Uganda beyond my youthful impressions, the work of Mahmood Mamdani offered me a far deeper, more sobering lens—revealing the political currents and historical wounds beneath the beauty we had so casually admired.

What makes Slow Poison instantly gripping is not merely Mamdani’s brilliance as a scholar, but the far rarer gift he brings to this book: the authority of one who lived the history he recounts. Read more »

by Steve Szilagyi

The appetite for Beatles product cannot be sated. Last month, Apple Corps Ltd. released Anthology 4, a new compilation in The Beatles Anthology series, as part of a broader thirtieth-anniversary remastered Anthology Collection. The Anthology series, for those who don’t know, consists of newly mixed outtakes of Beatles songs, previously unreleased tracks, and updated mixes of the two “new” Beatles songs, “Free as a Bird” and “Real Love.” That is 155 tracks of Beatles music presented in alternate versions—versions that are, in most cases, markedly inferior to the originals.

Most Beatles fans already own these songs in their original incarnations on LP, CD, and MP3—along with the many remastered, remixed, reordered, and reissued versions that have appeared since the Beatles’ catalog was belatedly released on CD in 1987. Since then, we’ve had authorized issues of the BBC radio recordings, the failed Decca audition tapes, and the long-circulating Star-Club Recordings. And serious Beatles obsessives have, for decades now, been trading bootlegs: hundreds of alternate takes, studio chatter, Christmas messages, and fan-club recordings.

Yet despite this surfeit, Anthology 4 debuted in the Top Ten on five Billboard album charts. This comes only a few years after the public turned Peter Jackson’s eight-hour Beatles band-practice documentary, Get Back, into a critical, financial, and strategic success for Apple Corps and Disney+. Read more »

by Laurence Peterson

If you have to argue, you’ve already lost. —Unknown

There is so much about the Trump regime that is troublingly peculiar: the base cruelty, the arrogant racism and sexism, the evangelistic ignorance, the fearless disregard for existing law, the super-conspicuous corruption; one can go on and on. What I want to focus on here today is how he, and his toadies and operatives in the administration, lie to all of us. As I shall try to explain below, the intention underlying the lies can vary somewhat depending on the part of the population being addressed at any given time, but one feature seems to stand out in almost all of the messaging: the content of the communication is not as important as the expression or implication of possible contempt for the recipients of that content.

Just in the last few days, Trump has escalated the military buildup off Venezuela to such an outsized point that it is rather clear that an attempt is being fostered to instigate a commission of some kind of rash mistake (by either side, with only the slightest degree of plausible deniability) that will result in hostilities between Americans and Venezuelans (or Colombians), which would then result in a manufacture of consent amongst the American electorate to tolerate a more vigorous attempt at regime change than they seem to be willing to countenance right now. It is also evident that there are other forces in the administration pushing in other directions, and that Trump enjoys playing them off against each other, but commitment to the first component appears to be the dominant component of Venezuela policy. Whatever the outcome of the jockeying, the Trump stance has (until very recently) been consistently expressed as an attempt to combat the importation of illegal drugs into the United States, especially fentanyl and cocaine, despite the demonstrated fact that Venezuela plays at best a very minor role in the trafficking of either drug to the US. In the very midst of all this, Trump pardoned the ex-President of Honduras, Juan Orlando Hernandez, who was convicted by a US court (and imprisoned there), of, you guessed it, trafficking 400 tons of cocaine into the US. Hernandez is even alleged to have said “We are going to shove the drugs up the noses of the gringos, and they won’t even know it.”

Also in the last few days, The Guardian reported that Trump owned two mortgages he claimed were primary dwellings, the very charge that Trump directed his Department of Justice to (unsuccessfully) indict former New York City prosecutor Letitia James on. James, it will be remembered, was the prosecutor who in 2022 filed a civil suit against Trump that resulted in penalties and a fine of four hundred million dollars (which was later voided as excessive; James plans to appeal this).

I have chosen these incidents as illustrative of my contention because they are so obviously contradictory and involve actions so hypocritical that it is impossible, if one is paying any attention to them at all, to avoid a conclusion that Trump and his administration have absolutely no respect for the recipients of this information, or that they are at all concerned about any possible consequences of presenting such blatantly offensive duplicity as its modus operandi to innumerable multitudes of citizens. They are, in the most direct way, putting up the biggest of middle fingers to the very ones they took an oath to serve and protect. How is this possible? What does it mean that we have come to this absurd point? Read more »

by Carol A Westbrook

Who can remember back to the first poets,

The greatest ones,…so lofty and disdainful of renown

They left us not a name to know them by —Howard Nemerov, The Makers

In this poem, Howard Nemerov, Poet Laureate from 1988-1990, reminds us that we have no idea when poetry—that is speech—began. The origin of speech is lost in the depths of prehistory, but archaeologists are working hard to get a better understanding of how speech began, because it is one of the few things that makes us unique as human beings.

Social animals communicate in order to coordinate activities, share resources, and improve their chance of survival. There are many examples of animals communicatio: bees, for example, do an elaborate dance to tell others where they found food; whales and elephants also exchange information and coordinate activities. But humans are the only animals that communicate by speech.

At one time it was thought that closely related animals like the great apes, chimps and bonobos would be capable of speech if only they were raised like human babies. There were several attempts to do this by raising young chimps in human families and monitoring their acquisition of language. But while these chimps learned to understand some human speech, they fell far behind their human brothers and sisters in vocalizing more than a word or two. They never learned to speak properly more than a few words, and it soon became apparent that these apes must have been lacking certain anatomic features that were present only in humans.

Scientists have a fairly comprehensive understanding of the evolution of the human species, supported by the fossil record and DNA studies.

As seen on the picture on the right, our likely earliest ancestor is called Australopithecus, and is thought to have existed about 3.4 million years ago (mya).. The term Hominid (Family Hominidae) includes all great apes including humans (orangutans, gorillas, chimps, bonobos, and us) while hominim (Tribe Hominim) is a narrow group within hominids, referring specifically to modern humans, our extinct ancestors, and all species more closely related to us than the chimpanzees, after our evolutionary split from chimpanzees. After Australopithecus came homo habilis, the maker, who made and used stone tools. Next came homo erectus, who used fire; then came Neanderthal and Homo sapiens, two species who evolved from a common ancestor. At what point did speech arise? Read more »

by Dilip D’Souza

On a stargazing trip between September 19 and September 23 this year, I spied a supernova.

Well, not quite. I took plenty of photographs of a spectacular night sky through the four nights I spent out in the open. Then I came home and looked through them, still filled with wonder at what I had captured. Then I read some astronomy news. Then I returned to my photographs and looked through again, this time in some frantic urgency.

Then I had to (figuratively) sit down. For there it was. The supernova. In my photograph.

That is: On September 23, there was news that an amateur astronomer in Australia, John Seach, had discovered a supernova in Sagittarius two days earlier. In fact, and astonishingly, he had discovered two supernovae on successive days. The brighter of the two was only visible in the Southern hemisphere. But the other one was in the constellation of Sagittarius. Because I had pointed my camera at the Milky Way so often through my trip, Sagittarius was in several of my photographs.

I pored over all of them. I had several images from before September 21, and several more from after. All I needed to do was find a dot in a post-September 21 photograph that wasn’t there in a pre-September 21 photograph. You might wonder how, in images with thousands of dots – that’s how spectacular the night sky was – I could even think of finding a specific one. But the report from Australia had an image locating the supernova just “below” Sagittarius. So I knew pretty much exactly where in my photographs to look for it.

And to my amazed delight, I actually did find such a dot, precisely where I expected it. There on September 22. Not there on September 20. The supernova, on my laptop. Read more »

by David J. Lobina

‘…a los gritos de «¡Viva España!» «¡Viva La Legión!» muere a nuestros pies lo más florido de nuestra compañías…’ —Franco, Diario de una Bandera [i]

In these times in which the term ‘fascism’ is forever abused, especially in the English-speaking world, and more specifically in the US, where large swathes of the liberal intelligentsia have convinced themselves that they are living through actual fascism,[ii] it is perhaps inevitable for the hispanist historian Paul Preston to be asked, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Francisco Franco’s death, why he is not so keen to call Franco a fascist (and, by extension, Francoist Spain a fascist state). And a historian’s answer he provides (not my own translation, because I am lazy, though I have edited it; my emphasis):

The use of the word “fascist” is a problem for me. If you ask me what a fascist is, I would say that the clearest example is Mussolini’s Partito Nazionale Fascista. Everything else is different. The problem with the word is that it is used as an insult. Today we say that Trump is a fascist. But of course, I am a university professor, and when I was at Queen Mary, University of London, I taught a course on the nature of fascism where I always asked to what extent Nazism was a case of fascism, because the problem is that it is something much worse. And Francoism, in many ways, was also worse.

Furthermore, [Italian] fascism had a rhetoric of doing away with everything old, something that Franco did not have, as he supported large landowners and the aristocracy. The part about the violence, which many associate with fascism, comes in Franco’s case from being a colonialist military man, an Africanist. Without Africa, I don’t understand myself, he said. Just like the Belgian or British military of the time. That’s why I’m uncomfortable using the word fascist with Franco.

This is par the course for a historian, as I have stressed many times before at 3QD (see, for instance, this piece) – most historians of Fascism, Nazism or Francoism have always kept them quite apart conceptually, despite some prima facie clear commonalities, which seem to me to be overemphasised in general anyway.[iii] But no more of this argumentative line now.

More to the point of this series, and as the Preston’s quote alludes to, it is Franco’s experiences in North Africa that explain a great deal of both his own outlook and that of the milieu he surrounded himself with – and this is a better foundation to understand Francoism than any analogies to Italian Fascism, let alone Nazism. Read more »

by Mike Bendzela

In “Hawthorne and His Mosses,” Herman Melville’s effusive review of the Massachusetts writer’s collection of short tales, Mosses from an Old Manse, Melville utters, under a cloak of anonymity (“a Virginian Spending July in Vermont”) one the most homo-erotic bits of praise imaginable for another male writer: “[He] shoots his strong New-England roots into the hot soil of my Southern soul”! Reclining in his Vermont “hay-mow” with Hawthorne’s volume, the smitten Virginian notes “how magically stole over me this Mossy Man!” Indeed! Melville knew of what he spoke — of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s stories, that is, many of which have become classics, such as “The Birth-Mark” and “Young Goodman Brown.”

I mention all this not just because it’s awesome but because I want to pilfer Melville’s torrid statement to say this of Southern old time music:

“It shoots its strong Appalachian roots into the chilly soil of my Northern soul”!

I use Clifftop here as an avatar for this last essay excursion into how the culture of the American South has had a life-changing effect on me: Its myriad old time tunes have possessed me for about twenty-five years now. Clifftop, West Virginia is the location of Camp Washington-Carver, site of a yearly festival of old time fiddle and banjo music, the Appalachian String Band Music Festival. This festival is rustic, acoustic, genuine, low-tech, and — happily — takes place on top of an actual doggone 2500-foot hilltop, surrounded by dense deciduous forest. I’ve been to this mecca of old time only twice, the two trips twenty-two years apart, for a total of about seventy hours of non-stop jamming; but it’s effect on me has been profound, sort of like Saul of Tarsus seeing the Risen Christ, or something like that. Read more »

by Peter Topolewski

Before the violence in the movie Bugonia moves center screen—and the narrative takes a not completely unexpected left turn—it’s made clear Teddy’s paranoia and consuming conspiracism and violent nature all have roots in childhood trauma. Things like child molestation and the hospitalization of his drug addled mother.

Oh gawd, you think, another movie explaining away awful behavior with a hellish upbringing. Seen it a million times, it’s boring already.

Boring in a movie, maybe, but that’s real life. Except it’s not only trauma that explains rotten behavior. Everything up to this moment in time explains everything about you, everything you’ve done, you’re about to do, and ever will do. This according to Robert Sapolsky, neuroscientist and author of Determined. You have no free will, your actions are determined by your genes, your environment, and your experiences. You have control over none of them.

His book, a couple years old now, has been well reviewed and discussed right here on 3 Quarks Daily, and there’s no need to do so again. The book feels like a mess at times, but an enjoyable one. And the choices—yes choices—Sapolsky made while writing the book are fascinating, the details of the science both enlightening and staggering, his purpose for writing it never more vital. And the implications are a trip. There’s no reason to carry on with this, but I have no choice but to go on, no more choice than I had to stop reading Determined, no more choice than Sapolsky had writing it.

Did he write it? Read more »

Car in a parking lot with frost on the ground.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Mark Harvey

The dark power at first held so high a place that it could wound all who were on the side of good and of the light. But in the end it perishes of its own darkness… —I Ching, #36, Ming

Years ago, someone gave me a copy of the I Ching, Book of Changes, translated by Richard Wilhelm. It’s a heavy little brick, more than 700 pages, and bound with a bright yellow cover. When I received the gift, I looked at it skeptically and never expected to read it. To my surprise, it’s been with me ever since, I’ve read it dozens of times, and the spine of the book is sadly broken from too many readings.

I grew up in a family with fairly skeptical parents and some very skeptical siblings. I vividly remember asking my parents if Santa Claus was real at an age when parents should definitely not disillusion a child of that belief. My parents looked at each other with pained expressions and then, too honest to lie about it, tried to let me down gently. So nothing in my formative years prepared me to like the I Ching.

Not all I Chings are equal, and there are some pretty flimsy versions out there. There’s even an app called I Ching Lite. Of the English versions, the Wilhelm/Baynes translation is one of the most respected.

The I Ching is said to be almost 3,000 years old and originated in China’s Zhou Dynasty. The structure consists of six stacked lines (called hexagrams), each either broken or unbroken. You’ll remember from your high school math that if you have two binary options (broken or unbroken) on six lines, you end up with 64 possible combinations. And that’s what the I Ching looks like: 64 hexagrams, each with its own special meaning. Read more »