by Ada Bronowski

One of the amusing things about academic conferences – for a European – is to meet with American scholars. Five minutes into an amicable conversation with an American scholar and they will inevitably confide in a European one of two complaints: either how all their fellow American colleagues are ‘philistines’ (a favourite term) or (but sometimes and) how taxing it is to be always called out as an ‘erudite’ by said fellow countrymen. As Arthur Schnitzler demonstrated in his 1897 play Reigen (better known through Max Ophühls film version La Ronde from 1950), social circles are quickly closed in a confined space; and so, soon enough, by the end of day two of the conference, by pure mathematical calculation, as Justin Timberlake sings, ‘what goes around, comes around’, all the Americans in the room turn out to be both philistines and erudite.

One of the amusing things about academic conferences – for a European – is to meet with American scholars. Five minutes into an amicable conversation with an American scholar and they will inevitably confide in a European one of two complaints: either how all their fellow American colleagues are ‘philistines’ (a favourite term) or (but sometimes and) how taxing it is to be always called out as an ‘erudite’ by said fellow countrymen. As Arthur Schnitzler demonstrated in his 1897 play Reigen (better known through Max Ophühls film version La Ronde from 1950), social circles are quickly closed in a confined space; and so, soon enough, by the end of day two of the conference, by pure mathematical calculation, as Justin Timberlake sings, ‘what goes around, comes around’, all the Americans in the room turn out to be both philistines and erudite.

A contradiction in terms? Not so fast and not so sure. Firstly, such confidences are made to the European in the room, identified as anyone from the old continent whose mother-tongue is not English and who is thereby draped with the aura of natural bilingualism – the key to culture. Like Theseus’ ship, the European is both up-to-date and very very old and therefore, involuntary tingling from the direct contact with centuries of history and civilisation. A position which, from the point of view of the American colleague, is not without its own contradictions: for if the oceanic separation awakes a nagging complex of inferiority from the erudite philistine, who fills the distance with fantasies of the old world and the riches of Culture, which (white) America has been lusting over from the Bostonians to Indiana Jones, it is a distance which also buttresses the sense of self-satisfaction suffused within the American psyche, and which, in the world of academia, has evolved into the self-made scholar. Yet another oxymoronic formula which brings us back to ‘the enigma wrapped up in a mystery’ that is the erudite philistine.

Two fundamental principles lie at the heart of this strange bird, the first, that you are always secretly guilty of what you blame others; the second, that you are always somebody else’s philistine. Read more »

Sa’dia Rehman. Allegiance To The Flag on Picture Day, 2018.

Sa’dia Rehman. Allegiance To The Flag on Picture Day, 2018.

In the first round of this year’s NBA playoffs, Austin Reaves, an undrafted and little-known guard who plays for the Los Angeles Lakers, held the ball outside the three-point line. With under two minutes remaining, the score stood at 118-112 in the Lakers’ favor against the Memphis Grizzlies. Lebron James waited for the ball to his right. Instead of deferring to the star player, Reaves ignored James, drove into the lane, and hit a floating shot for his fifth field goal of the fourth quarter. He then turned around

In the first round of this year’s NBA playoffs, Austin Reaves, an undrafted and little-known guard who plays for the Los Angeles Lakers, held the ball outside the three-point line. With under two minutes remaining, the score stood at 118-112 in the Lakers’ favor against the Memphis Grizzlies. Lebron James waited for the ball to his right. Instead of deferring to the star player, Reaves ignored James, drove into the lane, and hit a floating shot for his fifth field goal of the fourth quarter. He then turned around

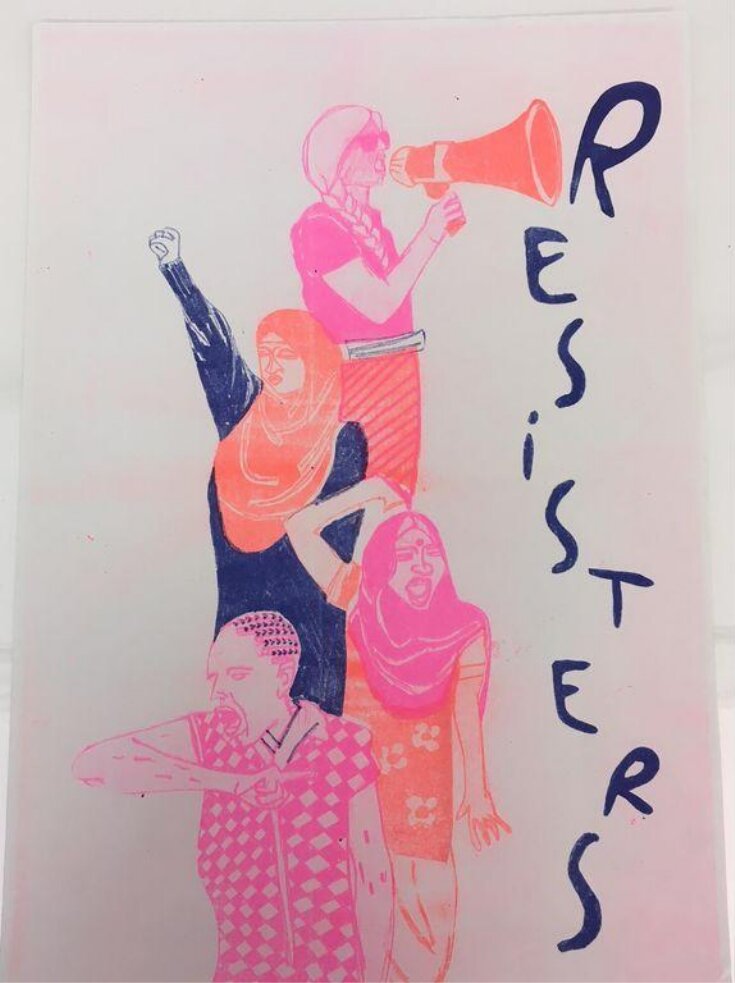

Aqui Thami. Resisters, 2018.

Aqui Thami. Resisters, 2018. I can’t sing. Or so I always thought. A notorious karaoke warbler, I would sometimes pick a country tune, preferably Hank Williams, so that when my voice cracked, I could pretend I was yodeling. Then one night, I stepped up to the bar’s microphone and sang a Gordon Lightfoot song.

I can’t sing. Or so I always thought. A notorious karaoke warbler, I would sometimes pick a country tune, preferably Hank Williams, so that when my voice cracked, I could pretend I was yodeling. Then one night, I stepped up to the bar’s microphone and sang a Gordon Lightfoot song.

My father’s mother—Annie Newman, my grandmother or Bubbi—was born Hannah Dubin in a shtetl in what is now Ukraine a few years before the Great War. One of her earliest recollections—in addition to the image of her own grandmother hiding in a baby carriage to escape marauding Cossacks—was of being able to see troop movements from the roof of her house, presumably during the Russian Imperial Army’s advance against Austria-Hungary, an engagement that occurred in Galicia, farther to the west, in 1914. Much later, in the aftermath of the nuclear accident in Chernobyl in 1986, when that obscure place was suddenly on everyone’s lips, she began recalling that her village, which she called Priut, in a region she referred to by its Russian name as Екатеринославская губернія, or Yekaterinoslavskaya guberniya—the Yekaterinoslav Governorate, a province of the Russian Empire—was not far from that site, which had now become infamous for a catastrophic meltdown.

My father’s mother—Annie Newman, my grandmother or Bubbi—was born Hannah Dubin in a shtetl in what is now Ukraine a few years before the Great War. One of her earliest recollections—in addition to the image of her own grandmother hiding in a baby carriage to escape marauding Cossacks—was of being able to see troop movements from the roof of her house, presumably during the Russian Imperial Army’s advance against Austria-Hungary, an engagement that occurred in Galicia, farther to the west, in 1914. Much later, in the aftermath of the nuclear accident in Chernobyl in 1986, when that obscure place was suddenly on everyone’s lips, she began recalling that her village, which she called Priut, in a region she referred to by its Russian name as Екатеринославская губернія, or Yekaterinoslavskaya guberniya—the Yekaterinoslav Governorate, a province of the Russian Empire—was not far from that site, which had now become infamous for a catastrophic meltdown.  A dear friend of mine recently passed away unexpectedly. He had recommended I read Viktor Frankl’s

A dear friend of mine recently passed away unexpectedly. He had recommended I read Viktor Frankl’s