by Rebecca Baumgartner

I don’t want to write this and you don’t want to read it. But this is the world we live in. As I write this, it’s been three weeks since a man without a criminal record legally purchased a trunk-full of guns, opened fire at the Allen Premium Outlets mall and killed eight people, including three children, and wounded seven others, all in the space of about three minutes. A place that previously had been known mostly for its contribution to traffic jams on Stacy Rd. will now be linked forever to white-shrouded bodies and blood splatters on the concrete outside the H&M store.

***

Because I live in a very conservative state, I’ve often had to swallow my true self, my beliefs, my reason, my outrage, my sadness, and my intelligence when listening to those around me speak about current events. A few years back, a conservative I know told me he was disturbed by the decision of his family’s school district to allow a trans person to serve as a substitute teacher for his daughter’s third-grade class. “I wasn’t prepared to talk to her about…all that yet,” he said, gesturing vaguely to indicate the existence of trans people. “I mean, she’s only eight.”

For complex reasons that any liberal living and working alongside conservatives in the Bible Belt will understand, I kept my response to a minimum. There was no point in telling him that talking about trans people with his daughter didn’t need to be a fraught conversation; it was really just about accepting people as they are and recognizing that difference exists. Eight-year-olds can understand that. In fact, it’s important that they understand that, because otherwise they will struggle to develop the empathy and emotional intelligence they need to connect with others who don’t see the world exactly as they do.

I had cause to recall that particular conversation when my son and niece asked me about the mall shooting.

“What happened?” they asked.

“Someone used a gun to shoot several people at an outdoor mall.”

“Why did he do it?” (Note that they both, aged nine, already knew to assume that the shooter was male. Kids really do pick up on a lot that we prefer not to talk about – the overwhelming maleness of violence being just one example.)

I gave a very inadequate and rambling answer to this question.

“Did anyone die?” my niece continued.

“Yes, several people.”

“Were any of them kids?”

In the pause before I gave the heart-crushing answer I had to give to that question, I thought back to that conversation about the trans substitute teacher and realized how insultingly trivial that conservative man’s concern had been, when compared with actual dead children.

I will never be prepared to talk about this to a child. Unlike conversations about sexuality and difference, there is no appropriate age to talk to children about heavily armed men killing children because they can. How easy and normal it is to talk to kids about the resplendent diversity of this world; how chilling and unnatural it is to talk about why our society takes such poor care of people that some of us reach the point of no return and others are more than happy to sell them guns on their way to whatever fresh hell they’re determined to create.

How do you talk to kids about dead kids? And how do you explain to them that this wasn’t a freak occurrence, but that it happens all the time – that, as a matter of fact, kids their age were gunned down at school almost exactly a year ago, in our very state, and absolutely nothing changed during that year that might have prevented this new tragedy, brought to our very town, right next to the burger place we like?

People say children are resilient. What they really mean is that children have no recourse but to accept the bullshit we put them through. What scares me is that mass shootings are such a common occurrence in our country that children like my son and niece will grow up accepting them as just another type of bullshit adults inflict on them. They will forget that we chose to live this way, and if we chose it, then we can change it.

In the days following the mall shooting, I read the email sent from my son’s school district, which included links to the American Psychological Association (APA) on how to talk to children about “difficult topics.” I’ll save you the time: they don’t have a clue either. All we get from the brightest minds in American psychology are common-sense bromides that seem geared toward toddlers or particularly uninquisitive older kids: Make them feel safe. Listen. Ask them what they already know. Tell them to look to the helpers. Limit exposure to the news. Make sure they get enough sleep. Thanks, APA.

When we ask kids what they’ve heard about the event, the idea is that we, the well-informed adults, will be able to correct any misconceptions and dispel any rumors. But what’s not addressed by the APA is what to do if your kid knows the truth, and the truth is more ghastly than any rumor could possibly be. And we’re supposed to reassure them and let them know they’re safe. But are they? If you can be killed while shopping, or at school, or at the movie theater, are you really safe? If kids are scared, well, shouldn’t they be? Isn’t that the rational response?

But the piece of advice that sticks in my craw the most is “Look to the helpers.” This is fine as far as it goes, but why do we only ever seem to have helpers and not preventers? Why are the people who are supposed to keep us safe only showing up after there’s blood on the concrete? Surely it was the followers of this advice who, in the days and weeks after the Allen shooting, kept praising the cop that happened to be at the mall for unrelated reasons and took down the shooter. “Thank God he was there. Just think how many more people might have died!” These are the people who, if 100 people had died, would be thanking God that it hadn’t been 101. There’s never anything so horrible that you can’t thank God for it. Never mind the fact that no one needed to die at all. This “Look to the helpers” pablum is just Orphan-Crushing Machine feel-goodism, tinged with the shut-up-and-put-up mentality of the gratitude pushers. The correct headline is not “Police Officer Stops Shooter from Killing More than 8 People” but “NRA-Funded Politicians’ Failure to Pass Gun Control Leads to Deaths of 8 People.”

Hero worship doesn’t prevent the next tragedy. Putting too much stock in the idea that it “could have been worse” obscures the idea that it didn’t have to happen at all. Instead of looking to the helpers, we should get angry at the ones who allowed it to happen in the first place.

I have a feeling that the people intent on focusing our attention on praising the cop rather than questioning why his bravery was necessary in the first place are the same people wearing “Allen Strong” t-shirts and stickers. This is what our pathologically positive society does when something horrifying happens: we pressure ourselves and others to get over it and move on as quickly as possible. Right after thoughts and prayers comes the “stay strong” rhetoric, as though the problem has been solved and now we just need to focus on managing and containing our emotional reaction to it. As though the real problem is how we think about the tragedy, not the tragedy itself.

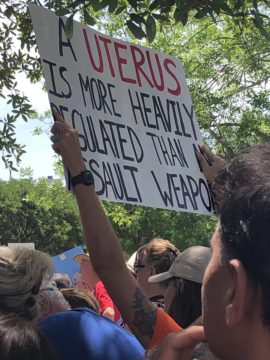

The Stoicism at the heart of this bullying insistence on “staying strong” is only coherent when there is no way to change your environment, when you have already tried every possible solution or when there are no solutions possible. Perhaps “stay strong” is good advice after something truly random and unpreventable strikes, like a tornado. But mass shootings are not inevitable; they are not a law of nature. And they are not random; they happen in places where people can easily acquire guns, and hardly ever happen in places where guns are difficult to acquire. (After all, up until the moment he pulled the trigger, the gunman was “a good guy with a gun” who had legally purchased his guns, had no criminal record, and was protected by Texas’ open-carry laws.) Unlike natural disasters, mass shootings have discernible human causes and catalyzing factors, as well as a smorgasbord of possible solutions across the political spectrum to pick from, including everything from, at the most conservative end, requiring background checks at gun shows, all the way to repealing the Second Amendment at the most progressive end. We have not tried every solution. In fact, in some states, like Texas and Tennessee, the highest in the land don’t even think there’s a problem at all, much less tried to solve it. They say things like “We’re not gonna fix it. Criminals are gonna be criminals.” They’ve created a world in which a teenager in Texas can buy a semi-automatic weapon before they’re legally allowed to drink a beer. They’ve created a world in which the leading cause of death for children in America is guns. And they pretend that this is out of our control, just one of the mysteries of life, rather than a deliberate effort to, in Jon Stewart’s words, “bring chaos to order.”

But this is a human problem, with human solutions. Stoicism and “staying strong” is not an appropriate response when action is still on the table. And as long as we claim to live in a democracy, action is always on the table. As the authors of the Commonweal piece “Getting Used to It” write, describing how quickly Americans move on after each senseless massacre, “Call this attitude exhaustion or call it callousness. Just don’t call it resilience: there are things one shouldn’t get over too quickly, and things one should never get used to.”