by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

In Arkady Martine’s 2019 debut novel A Memory called Empire, newly-appointed Ambassador Mahit Dzmare travels via jumpgate from her home planet at the edge of the Teixcalaani empire to the capital. Teixcalaan is like the sun around which all the other planets in the empire revolve. The city of cities, it is the center of the Teixcalaani universe.

Arriving in the capital, the new ambassador is immediately invited to attend a gathering of the glittering literati at court. Mahit stands in awe of what to her eyes is the pinnacle of civilization. The gathering doubles as a poetry contest. And as she listens to a recitation of a poem of self-sacrifice at war, which simultaneously spells the name of one of the lost soldiers in the opening glyphs of each line, Mahit realizes that right here, in this very place, is everything she has wanted since she was a young girl back on her home planet at the edge of the empire.

The novel is, not surprisingly, dedicated to “anyone who has ever fallen in love with a culture that is devouring their own.”

Memory Called Empire received the 2020 Hugo Award for Best Novel. It has also gotten some attention from linguists.

The written language of the empire, Teixcalaanli, is based on the Aztec hieroglyphics of Mesoamerican language Nahuatl, which was the language spoken in central Mexico before the arrival of the Spanish. A logosyllabic tongue written in glyphs like Chinese, the script allows for wonderful poetic artistry and playful wordplay.

I don’t think many students of Japanese language and literature –especially those of classical Japanese—would miss the affinity to the poetry contests and glamor of the Heian court. Reading as protagonist Mahit tries to display her own growing cultural prowess through her ability to make nuanced references to literary tropes, mainly from poetry, it really did feel straight out of the Tale of Genji. According to Martine, in addition to Nahuatl, Teixcalaanli is also inspired by Byzantine Greek. Digging around online, I discovered that poetry contests were a centerpiece of political life during the Middle Byzantine Period (approximately 900-1204 CE), and were used in much the same way as in the Heian court: to prove an orator’s intelligence and cultural competence, as well as to make political arguments.

What do we have nowadays to gain cultural capital? Definitely not impromptu poetry contests at the parties of the powerful.

2.

In University of Bologna linguist Silvia Ferrara’s new book, The Greatest Invention: A History of the World in Nine Mysterious Scripts (translated wonderfully by Todd Portnowitz), the author emphasizes the way a written script is never inherently tied to its language. Think of how Chinese characters have been used by languages as linguistically different from each other as Vietnamese, Korean, Cantonese, and Japanese.

And how many languages are written using modified forms of the Roman alphabet?

With so many writing systems, I wondered how Ferrara whittled the list down to just nine scripts in her attempt to pinpoint the miracle of “true invention.” As a Japanese translator, right off I was wondering why the two Japanese syllabaries, hiragana and katakana were not included. Japanese is unique in world languages to employ three different scripts to notate its oral language.

Also excluded was the Phoenician alphabet (from which Greek as well as our Roman alphabet is derived).

Her reason for this was that each of these scripts above were themselves derived from other scripts; in the case of hiragana and katakana from Chinese characters and in the case of Phoenician from Egyptian hieroglyphs by way of something called the Proto-Sinaitic script.

Teixcalaani, while having cultural-semantic elements from Byzantine Greek such as diglossia, has a writing system that is pictographic, like the Aztec script used to write Nahuatl.

Martine’s novel illuminates Ferrara’s point about scripts being fundamentally detached from their languages since Martine was able to come up with a language semantically like Greek but being written in logographs.

3.

3.

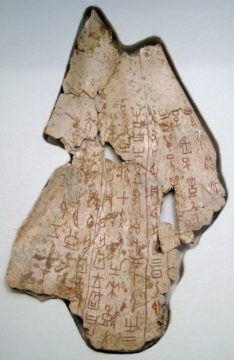

It is not surprising that most of the world’s scripts were influenced by other scripts. I think it is hard to pinpoint any true inventions. Though, the cuneiform writing of the Sumerians is a maybe safe bet—being considered the oldest writing form. This is followed by Egyptian hieroglyphs, and Chinese characters, or logograms. Less well known are the Indus script and the Olmec script of Mesoamerica; as well as Rongorongo of Easter Island.

Right off, readers might notice that except for Chinese, none of these scripts is used by the same people anymore.

So, in that sense, the greatest invention is Chinese—given both its beauty and longevity.

Scripts, like languages are fragile. Also, of the nine, more than half are as yet undeciphered: Linear A, Cretan Hieroglyphics, the Cypro-Minoan syllabary, the Indus script, Meso-American Olmec and yes—Rongorongo.

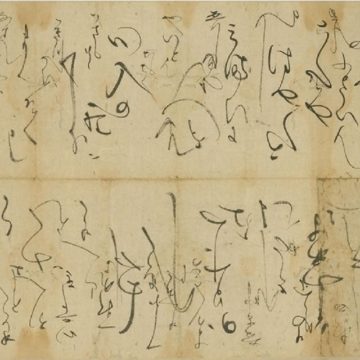

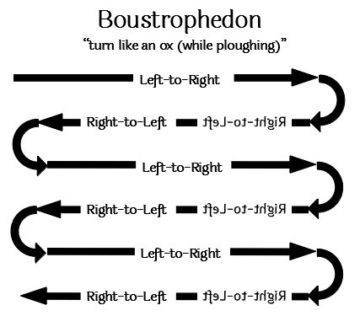

Not much is known about Rongorongo. Scholars believe it was created to notate the language of Rapa Nui, used on Easter Island, one of the most remote places in the world. One interesting thing about the script is that it was written in reverse boustrophedon. I had never heard that phrase before. As a Japanese translator, I deeply admire and find it pleasing to read Japanese texts vertically, from top to bottom, right to left. Classical Japanese, usually written vertically, did not employ punctuation so sentences merged and flowed without pause.

Not much is known about Rongorongo. Scholars believe it was created to notate the language of Rapa Nui, used on Easter Island, one of the most remote places in the world. One interesting thing about the script is that it was written in reverse boustrophedon. I had never heard that phrase before. As a Japanese translator, I deeply admire and find it pleasing to read Japanese texts vertically, from top to bottom, right to left. Classical Japanese, usually written vertically, did not employ punctuation so sentences merged and flowed without pause.

What is so interesting about boustrophedon systems is that the text is written in the same way an ox plows a field; so that lines run left to right and then right to left, alternating down the page. The Greek words means “writing that follows the path of the ox.” But Rongorongo is written in reverse boustrophedon, which means the signs in the second line are upside down with respect to the first, forcing the reader to turn the tablet over every other line. Not only that, but the language is read from bottom to top… reading is quite physical!

4.

According to Ferrara, scripts evolve from icons.

They are at base: art.

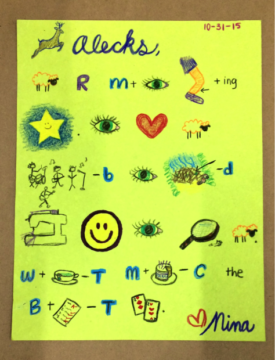

From basic pictographs development occurs by the “rebus effect.” This happens when existing symbols, such as pictograms, are used a second time purely for their sound, regardless of their meaning, to represent new words. An example Ferrara provides is the Chinese character 洋, “ocean,” which is a combination of the images for “water,”氵, and “sheep,”羊. She writes:

On the semantic level, obviously, “sheep” has no business being a part of this word, but on the phonetic level it does, since it is pronounced just like “ocean,” yang. It’s a marvelously coherent system, with meaning and sound coming together to form each sign. Like inserting one thing into another with a satisfying click. This fusion, this click, is unique. Which is why calling the Chinese script “ideographic” is an indignity, not to mention an error.

In ancient history, rebuses were a kind of lightbulb moment when a homonym was discovered to work well in conveying words with very different meanings but that sound the same. Another example comes from the earliest writing system discussed in the book: Cuneiform—in this case used to write the ancient language of Sumerian 3,000 years before Christ.

In ancient history, rebuses were a kind of lightbulb moment when a homonym was discovered to work well in conveying words with very different meanings but that sound the same. Another example comes from the earliest writing system discussed in the book: Cuneiform—in this case used to write the ancient language of Sumerian 3,000 years before Christ.

So much Cuneiform is concerning ledgers and accounts receivables… market lists and money owed. A scribe jotting down debts owed to a temple realizes that the sound for “to reimburse” sounds the same as for “cane” (as in a reed) and Presto! He draws a cane.

Later in the book, Ferrara describes a game of Pictionary where players are trying to communicate Brad Pitt. They draw a man and try to make it look like him. When that doesn’t work they draw a man next to a beautiful woman with flowing hair… still, no cigar. Success is arrived at by putting a peach with an arrow pointing to the dark ‘pit’ in the center of the fruit. Ah ha!

5.

Something missing from A Memory Called Empire is the way that language shapes thoughts in the bilingual brain. Reading the novel, you never sense that Mahit is thinking—or dreaming—in Teixalaani. She has another voice in her mind, that of the former now-deceased ambassador, whose memory has been installed in her brain as an imago, a high technical achievement invented on her home planet. How something so technologically advanced was achieved out in the sticks of space is part of the fascination of the novel. But the now-dead former ambassador and Mahit communicate silently inside her mind in the Stationer language, which is an alphabetic language, heavy in consonants—not unlike, the author points out in a note in the back of the book, Modern Armenian.

As I have mentioned in these pages numerous times, I felt like a different person in Japanese. I certainly said thank you more often, and I believe I became more considerate and compassionate. In spoken Japanese there was an element of fun since verbs come at the end of sentences. Endless jokes could be made. The listener thinks you are going in one direction, only to be surprised when the action verb arrives and the whole sentence means something completely different. I listened more carefully than I did in English waiting for the verbs. Spoke slower, trying to be polite.

But even more than the transformation I felt in speaking Japanese was how dramatic it was to read and write. Because many Chinese characters, called kanji in Japanese, function like pictographs (logograms), meaning is not necessarily tied to the verbal language, so you can skim and grasp meanings without actually reading. Instead of proceeding “in time” from left to right sounding out what the words say in your mind, for example, you see a character and immediately know what is being conveyed. As a simple example, 山 means “mountain” no matter what language you speak. And when you “see” the character you grasp the meaning instantly.

In Ted Chiang’s first story collection Stories of Your Life and Others, one of the stories, called “The Story of Your Life,” explores communication with aliens who visit earth. Are the friends? Or enemies? To try and find out a linguist is called in. Unable to crack their oral language she turns to their written script. Discovering that their language, Heptapod, is not unlike Chinese, in that often meaning is conveyed in the structure of characters (semasiographic) rather than the pattern of phonetic, vocalized sounds (glottographic).

In Ted Chiang’s first story collection Stories of Your Life and Others, one of the stories, called “The Story of Your Life,” explores communication with aliens who visit earth. Are the friends? Or enemies? To try and find out a linguist is called in. Unable to crack their oral language she turns to their written script. Discovering that their language, Heptapod, is not unlike Chinese, in that often meaning is conveyed in the structure of characters (semasiographic) rather than the pattern of phonetic, vocalized sounds (glottographic).

Taking it further, Heptapod logograms can convey the meaning of entire sentences. In the story, as the hero becomes fluent in the language, which conveys all the semantic pieces of the sentence instantaneously, she experiences a great shift in how she understands time and her place therein; so that the future is already present– in that precise present moment. The idea is something akin to reading kanji-dense Japanese sentences that if you comprehend meaning instantaneously instead of experiencing it unfolding in time (reading from the start of a sentence to its end), you come to perceive the future and present bound in a single instant. The language unlocks the door to a new perception of existence in time.

In the same way that the language we think in changes our thoughts, so too does the language we read in open new pathways of understanding.

6.

Thinking about the “pit” in Brad Pitt, Silvia Ferrara again and again makes the point that scripts, like oral languages, are not inventions but more like activities that evolve collectively–in groups of people.

This can be better understood when comparing it to artificial languages which are invented, like Klingon or Loglan. Arika Okrent, in her delightfully fun book In the Land of Invented Languages: Esperanto Rock Stars, Klingon Poets, Loglan Lovers, and the Mad Dreamers Who Tried to Build A Perfect Language, introduces an array of people who, often obsessed with languages as kids, go on to spend their lives constructing incredibly rich artificial languages–all for a population of one person. Themselves.

This can be better understood when comparing it to artificial languages which are invented, like Klingon or Loglan. Arika Okrent, in her delightfully fun book In the Land of Invented Languages: Esperanto Rock Stars, Klingon Poets, Loglan Lovers, and the Mad Dreamers Who Tried to Build A Perfect Language, introduces an array of people who, often obsessed with languages as kids, go on to spend their lives constructing incredibly rich artificial languages–all for a population of one person. Themselves.

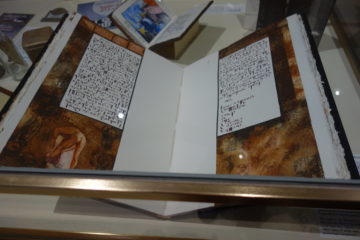

I had never heard of this before, but it is called Conlanging (constructed languages)– but I really went down the rabbit hole reading about it. Probably what first comes to mind, in addition to the Heptopod language above, are the languages from the Hobbit and Lord of the Rings, or Dothraki and Klingon from Game of Thrones and Star Trek. Artist and conlanger Steven Travis’ constructed language Tapissary stands out for the rich beauty of his made-up script, which is incorporated into works of art in charcoals and oils, as well as illuminated manuscripts.

7.

During Covid, many people began to study languages. With time on their hands and imaginations unlocked –ironically unlocked by lockdown– people craved connecting with others. And how better to do during a lockdown that then through language study?

In the US language learning has reached an all time low. Long gone are the days when students learned to read and write in French or Spanish, or in earlier times became proficient at ancient languages like Latin or Greek.

How much we are missing out because of this.

Especially attractive to me are the dead languages of cultures long past for their possibilities for opening up more archaic and timeless ways of being in the world. Think of all the metaphysical vocabulary in Sanskrit collected in Maria Heim’s Words for the Heart– or the way Ann Patty in her memoir, Living with a Dead Language describes reading ancient Roman poetry with its concepts of empire and paganism. Like learning a stringed instrument, the older one gets the more challenging language learning becomes, and Ann Patty decides to stay mentally fit by taking up Latin at the age of 57. Language learning, she concedes, is an activity for young people with their more plastic minds….. and yet, the allure of finding onself reborn by thinking in a new language remains strong.

One of the most interesting parts of Katherine Russell Rich’s book Dreaming in Hindi was her conversations with experts about the way writing and speaking are so different for language learners. While attaining native ability of a spoken language is impossible after a certain age, writing a different script is not as age-sensitive. Non-natives can become very good at writing characters.

Many past U.S. presidents were proficient in one or more foreign languages, and through Theodore Roosevelt this often included the languages of Homer and Virgil. James Garfield was perhaps most famous for being ambidextrous and it is said could simultaneously write both Greek and Latin (one hand for each).

Those days are long gone: oh, how the mighty have fallen!

++

To read:

Natural Languages

My Substack post about Japan: “Oracle Bones and Writing in the Time of the Gods”

Silvia Ferrara’s new book, The Greatest Invention: A History of the World in Nine Mysterious Scripts (translated wonderfully by Todd Portnowitz)

Jin Tsu’s Kingdom of Characters: The Language Evolution that Made Modern China

Katherine Russell Rich’s Dreaming in Hindi

Ann Patty’s Living with a Dead Language: My Romance with Latin

Maria Heim’s Words for the Heart: A New Book from Maria Heim

LANGUAGE AT THE END OF THE WORLD: The undecipherable rongorongo script of Easter Island

Jacob Mikanowski (Cabinet Magazine)

My Substack post: How Language Shapes on Hearts

Imaginary Languages

A Memory Called Empire (Teixcalaan, #1)

by Arkady Martine

Teixcalaanli is inspired by Nahuatl (… and Greek); Stationer is basically Space Armenian. I’m kinda a language nerd—Arkady Martine

Ted Chiang’s story Stories of Your Life and Others (and the film version Arrival–plus my 3QD essay here)

David J Peterson’s The Art of Language Invention

Arika Okrent’s In the Land of Invented Languages: Esperanto Rock Stars, Klingon Poets, Loglan Lovers, and the Mad Dreamers Who Tried to Build A Perfect Language

Steven Travis’ constructed language Tapissary

Arika Okrent, in her delightfully fun book In the Land of Invented Languages: Esperanto Rock Stars, Klingon Poets, Loglan Lovers, and the Mad Dreamers Who Tried to Build A Perfect Language

And the documentary: Conlanging, The Art Of Crafting Tongues