by Ada Bronowski

One of the amusing things about academic conferences – for a European – is to meet with American scholars. Five minutes into an amicable conversation with an American scholar and they will inevitably confide in a European one of two complaints: either how all their fellow American colleagues are ‘philistines’ (a favourite term) or (but sometimes and) how taxing it is to be always called out as an ‘erudite’ by said fellow countrymen. As Arthur Schnitzler demonstrated in his 1897 play Reigen (better known through Max Ophühls film version La Ronde from 1950), social circles are quickly closed in a confined space; and so, soon enough, by the end of day two of the conference, by pure mathematical calculation, as Justin Timberlake sings, ‘what goes around, comes around’, all the Americans in the room turn out to be both philistines and erudite.

One of the amusing things about academic conferences – for a European – is to meet with American scholars. Five minutes into an amicable conversation with an American scholar and they will inevitably confide in a European one of two complaints: either how all their fellow American colleagues are ‘philistines’ (a favourite term) or (but sometimes and) how taxing it is to be always called out as an ‘erudite’ by said fellow countrymen. As Arthur Schnitzler demonstrated in his 1897 play Reigen (better known through Max Ophühls film version La Ronde from 1950), social circles are quickly closed in a confined space; and so, soon enough, by the end of day two of the conference, by pure mathematical calculation, as Justin Timberlake sings, ‘what goes around, comes around’, all the Americans in the room turn out to be both philistines and erudite.

A contradiction in terms? Not so fast and not so sure. Firstly, such confidences are made to the European in the room, identified as anyone from the old continent whose mother-tongue is not English and who is thereby draped with the aura of natural bilingualism – the key to culture. Like Theseus’ ship, the European is both up-to-date and very very old and therefore, involuntary tingling from the direct contact with centuries of history and civilisation. A position which, from the point of view of the American colleague, is not without its own contradictions: for if the oceanic separation awakes a nagging complex of inferiority from the erudite philistine, who fills the distance with fantasies of the old world and the riches of Culture, which (white) America has been lusting over from the Bostonians to Indiana Jones, it is a distance which also buttresses the sense of self-satisfaction suffused within the American psyche, and which, in the world of academia, has evolved into the self-made scholar. Yet another oxymoronic formula which brings us back to ‘the enigma wrapped up in a mystery’ that is the erudite philistine.

Two fundamental principles lie at the heart of this strange bird, the first, that you are always secretly guilty of what you blame others; the second, that you are always somebody else’s philistine.

Being called an ‘erudite’ by his philistine colleagues is taken by the American erudite to be a backhanded compliment: erudition is the polite word for what people – the philistines – in fact consider to be pedantism and name-dropping. Being philistines, they regard as superficial what is in fact deep, mistaking mathematical perspective for an optical illusion.  But, in one sense, perspective is indeed an optical illusion – a very clever one. And so, whilst the philistine keeps his suspicions simmering over a low but constant heat, erudition itself is slowly eroded by those very same suspicions. For the erudite is only at one remove from his frenemy: to be an eruditus, as the Latin etymology makes clear, is to have extracted yourself from the quagmire, the crudeness of your surroundings. The erudite is an ex-crude, and so, the philistine and the erudite are two of a kind.

But, in one sense, perspective is indeed an optical illusion – a very clever one. And so, whilst the philistine keeps his suspicions simmering over a low but constant heat, erudition itself is slowly eroded by those very same suspicions. For the erudite is only at one remove from his frenemy: to be an eruditus, as the Latin etymology makes clear, is to have extracted yourself from the quagmire, the crudeness of your surroundings. The erudite is an ex-crude, and so, the philistine and the erudite are two of a kind.

One must not confuse the philistine with the barbarian. The philistine is the face in the mirror, and has been so since his first appearance of Biblical fame: David, the Israelite (the erudite jew with that clever trick: how to kill a man without a sword) opposite the Philistine Goliath, all muscles and gold; Samson, with his regrowing hair, against the Philistines, partying around their god Dagon. You win some you lose some. Each time, the philistine is the distorted image in the mirror: as a giant with Goliath, as a blood-thirsty mob opposite Samson. The philistine is not the unknown other. That would be the barbarian – an utterly different kettle of fish. As the Greek poet Constantine Cavafis (1863-1933) had already noted, there are no more barbarians to wait for. The philistines, on the other hand, are thriving, calling out, each to their own distorted reflection: ‘Philistine!’ from the erudite; ‘Erudite!’ from the philistine, ‘are you talking to me?!’. The one generates the other in a continual strive to extract ourselves from what is closest to us. David refuses the sword, to prove he has been extracted, elected, elevated … but… ‘what goes up, must come down’… says the song.

The erudite is trapped within his own condescension. He even, at times, applauds his colleagues’ so-called ‘erudition’ on the same caustic basis the people he deems to be philistines applaud his own erudition. He is thus caught between being secretly convinced of the worth of his true erudition and his understanding of the qualification in the mouth of his colleagues as a thinly veiled disparagement. It is a further principal that the more one is convinced of one’s depth, the more what one finds, deep within oneself, is an abysmal void… Paul Valéry (1875-1943) may have been right when he said that a man’s skin is what is most profound in him: the brilliant, moral twist in this idea is that, though we yearn for depth, striving for erudition, what we are fleeing (consciously or not) is facing the truths at the surface of our lives: they are the most complicated since they reveal how far we are from living in harmony with our closest circles as with the world at large. The erudite retrenches himself in depth from fear of facing his surface, it is a form of self-punishment: to go to the place where you know you will find the confirmation of your ineptitude. After the self-hating jew, we get the self-chastising erudite.

Paul Valéry (1875-1943) may have been right when he said that a man’s skin is what is most profound in him: the brilliant, moral twist in this idea is that, though we yearn for depth, striving for erudition, what we are fleeing (consciously or not) is facing the truths at the surface of our lives: they are the most complicated since they reveal how far we are from living in harmony with our closest circles as with the world at large. The erudite retrenches himself in depth from fear of facing his surface, it is a form of self-punishment: to go to the place where you know you will find the confirmation of your ineptitude. After the self-hating jew, we get the self-chastising erudite.

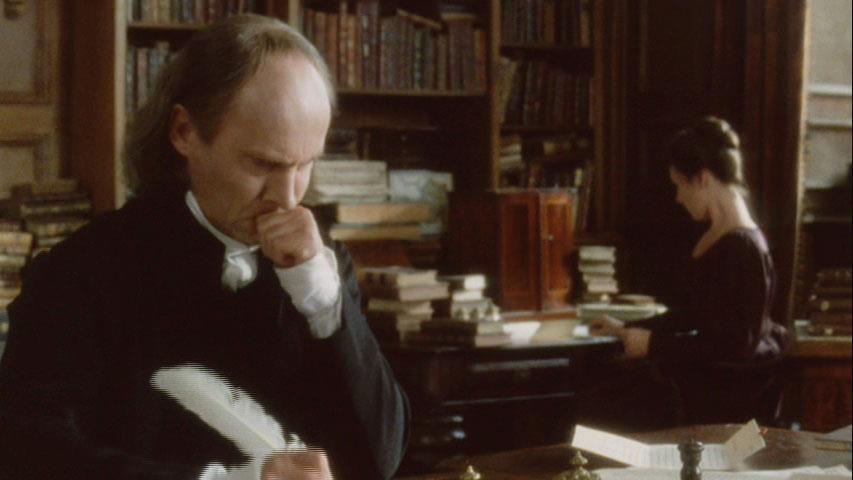

It is the predicament of one of literature’s greatest miserable erudites, Edward Casaubon, the pompous anti-hero of George Eliot’s Middlemarch (1872): the fusty old scholar who managed to seduce passionate young Dorothea, whose thirst for knowledge outweighed her drive for romanticism. How did he do it? By telling her – of all things! – about his ‘new theories on the Philistine king Dagon’. Spending his honeymoon in the libraries of Rome, leaving his young bride – in a prequel to Roman Holidays – to wander the city alone, the guarded walls of his erudition vacillate as Dorothea, less knowledgeable but more intelligent, realises that there are no new theories, no new book, only piles and piles of notes that grow by the day. Eliot herself, in her subtle irony, by focusing Casaubon’s erudition on a recondite detail of an impossibly obscure history of the original Philistines, gives us the portrait of the erudite as champion of the philistines.

She was inspired to name her character after a real-life Renaissance Humanist, the French, protestant, scholar and classicist Isaac Casaubon (1559-1614) who produced our first modern editions of the ancients from Aeschylus to Diogenes Laertius. This affiliation of fictional Edward Casaubon, who is the bane of Dorothea’s life, to real-life Isaac Casaubon betrays an ambiguity in George Eliot’s own relation to both erudition and philistinism. Dorothea chooses Casaubon, and not her first suitor, (shallow and facetious Chettam), because she thinks knowledge and understanding are what matter in this world. Her disappointment – which silhouettes Eliot’s own disappointments – consist not so much in abandoning her ideals, as realising erudition is not the path to them. Culture, i.e., life is elsewhere: wherever there is action, love and morality.

Casaubon himself realises the falsity of his position, first and foremost because of a crucial practical fact, that he does not know German – a lack which cuts him off from the greatest part of the scholarship on his very subject of erudition. He is thus both an erudite and not an erudite, lying to the outside world about his capacities and torturing himself inwardly with the double-awareness of the vanity of his travails and the necessity to keep up appearances, all the while convinced of the superiority of his own endeavours on those of everyone else’s, regardless. The self-biting, self-chastising erudite is the endgame of all paths of erudition. So obsessed not to fall prey to looming philistinism that the borders blur soon enough and no one – least of all the erudite – knows who the philistine is anymore.

Casaubon himself realises the falsity of his position, first and foremost because of a crucial practical fact, that he does not know German – a lack which cuts him off from the greatest part of the scholarship on his very subject of erudition. He is thus both an erudite and not an erudite, lying to the outside world about his capacities and torturing himself inwardly with the double-awareness of the vanity of his travails and the necessity to keep up appearances, all the while convinced of the superiority of his own endeavours on those of everyone else’s, regardless. The self-biting, self-chastising erudite is the endgame of all paths of erudition. So obsessed not to fall prey to looming philistinism that the borders blur soon enough and no one – least of all the erudite – knows who the philistine is anymore.

For the philistine is just as much the heir of history as is the erudite. An heir? Or perhaps, a victim. Vladimir Nabokov (1899-1977),  the great Russian-American writer, frames the philistine at the receiving end of multiple traditions which “have accumulated in a heap and have started to stink”. The stench, that is, comes not from the man but from the entanglement of a past so rich that it has lost all sense of order and hierarchy for a contemporary of the present, reduced to a state of philistinism malgré lui. The philistine is the end product of a civilisation, which has out-civilised itself. We are each someone else’s philistine, drowning in cultural surfeit: everything is something that might be important but no one knows which is more important anymore.

the great Russian-American writer, frames the philistine at the receiving end of multiple traditions which “have accumulated in a heap and have started to stink”. The stench, that is, comes not from the man but from the entanglement of a past so rich that it has lost all sense of order and hierarchy for a contemporary of the present, reduced to a state of philistinism malgré lui. The philistine is the end product of a civilisation, which has out-civilised itself. We are each someone else’s philistine, drowning in cultural surfeit: everything is something that might be important but no one knows which is more important anymore.

Nabokov was a specialist in philistinism, especially American philistinism – he wrote an essay on the topic, ‘Philistines and Philistinism’[1]; it is the subject of two of his greatest novels, Lolita (1955) and Ada or Ardor (1969). America, for this Russian emigré, educated at Cambridge, who lived and worked in Berlin, Paris, Prague then New-York to end his life at the Montreux Palace Hotel in Switzerland – a stone’s throw away from the Manoir de Ban where his almost exact contemporary, Charlie Chaplin spent the last years of his life – America’s very raison d’être is to put civilisation in crisis, precisely because it is such a receptacle, or rather a tumble-dry, of so many disparate traditions.

Lolita’s Humbert Humbert (in whom, by the by, some scholars have identified elements inspired from the life of Charlie Chaplin) incarnates the crumbling ruins of old Europe, the cultured man, who reads the world through the eyes of history and literature. He is sick with a fixation on a childhood love which has morphed into an obsession with ‘nymphettes’ – the word itself, a coinage which is a marker of his old-world culture, an erudite parody that covers the swathe of Western civilisation from Callimachus to Correggio. This paedophilic fixation emblematises the loss of order and the protagonist’s yielding to the degraded primitivism that he finds in New England where he lets loose his, until then, repressed penchant. The Americanised lingo, the amateur theatre, people’s clothing (especially Lolita’s mother whom Humbert marries to get closer to Lolita), the food, the chit-chat… everything oozes philistinism from every nook and cranny in the eyes of the European. But he does not remain an objective critic for long.

Lolita’s Humbert Humbert (in whom, by the by, some scholars have identified elements inspired from the life of Charlie Chaplin) incarnates the crumbling ruins of old Europe, the cultured man, who reads the world through the eyes of history and literature. He is sick with a fixation on a childhood love which has morphed into an obsession with ‘nymphettes’ – the word itself, a coinage which is a marker of his old-world culture, an erudite parody that covers the swathe of Western civilisation from Callimachus to Correggio. This paedophilic fixation emblematises the loss of order and the protagonist’s yielding to the degraded primitivism that he finds in New England where he lets loose his, until then, repressed penchant. The Americanised lingo, the amateur theatre, people’s clothing (especially Lolita’s mother whom Humbert marries to get closer to Lolita), the food, the chit-chat… everything oozes philistinism from every nook and cranny in the eyes of the European. But he does not remain an objective critic for long.

As long as he travels across the country with Lolita, shielding her from contact with others, he holds onto a manner of living set apart from American society, much like Casaubon resisting pathetically in the middle of the English gentry. But once Lolita escapes and Humbert, after searching for her for a couple of years, finds her, aged seventeen, married and pregnant, and discovers that he is truly in love with her, he utterly surrenders to his degenerate surroundings. The ‘stench’ has overcome him completely: he gives Lolita money and goes off to kill the man who took her from him, a philistine paedophile, a producer of porn films, Clare Quilty, not at all someone capable of mythologising the eternal ‘nymphette’. The minute the pretence to a superior access to culture is abandoned, however, there is no opposition. Humbert’s tragedy is to realise he is no better than Quilty. Everyone is as deplorable as everyone else.

With Ada or Ardor, the exact opposite movement takes place.  The protagonists, Ada and Van, descendants of an emigré Russian family, who discover that though officially cousins, they are in fact brother and sister, keep the philistines at bay through their incestual love affair. They rival in erudition ranging from literature to entomology, barricading themselves behind a wall, impenetrable to the rabble without. They even live in a world called ‘Antiterra’, which we never can be sure is their own invention for their own inner world, or the invention of the author for a fictional world in which everyone else lives as well; the confusion is deliberately maintained as the characters travel from familiar named places like New York, London or Switzerland.

The protagonists, Ada and Van, descendants of an emigré Russian family, who discover that though officially cousins, they are in fact brother and sister, keep the philistines at bay through their incestual love affair. They rival in erudition ranging from literature to entomology, barricading themselves behind a wall, impenetrable to the rabble without. They even live in a world called ‘Antiterra’, which we never can be sure is their own invention for their own inner world, or the invention of the author for a fictional world in which everyone else lives as well; the confusion is deliberately maintained as the characters travel from familiar named places like New York, London or Switzerland.

It is not by chance that Lucette, Ada’s younger sister, after Van rejects her advances, commits suicide while travelling on a transatlantic crossing, as if the passage from Europe to America, if not done from within the barricade of culture cemented through incest, means a loss to which death is preferable. Nabokov emblematises not the dichotomy of the erudite and the philistine but rather the consequences of a Culture which is fantasised and not lived. The incest between Ada and Van is the epitome of such a fantasy on the mind of a civilisation out of breath, suffocating under its own pretences to out-civilise the old world.

The incest also marks a manner of cultural autonomy between Ada and Van: they share between themselves their knowledge and emotional intelligence, denying even to Lucette an entry into this privileged ‘temple in which columns full of life, mumble indistinct words’ to Nabokovianly paraphrase Baudelaire. The author makes palpable in this way the ideal of a superior culture confined to the happy few that Ada and Van incarnate: children of emigré Europeans, cocooned, lest they stain themselves from the contact with ‘stinking’ America, outside. At the same time, their incestuous cocoon itself is rotten to the core – murderous even, since Lucette will pay the highest price for their superior isolation.

The incest also marks a manner of cultural autonomy between Ada and Van: they share between themselves their knowledge and emotional intelligence, denying even to Lucette an entry into this privileged ‘temple in which columns full of life, mumble indistinct words’ to Nabokovianly paraphrase Baudelaire. The author makes palpable in this way the ideal of a superior culture confined to the happy few that Ada and Van incarnate: children of emigré Europeans, cocooned, lest they stain themselves from the contact with ‘stinking’ America, outside. At the same time, their incestuous cocoon itself is rotten to the core – murderous even, since Lucette will pay the highest price for their superior isolation.

As long as there is – in the imagination – a superior form of culture, there is – in the imagination – an ambient philistinism, a form of cultural vulgarity that is a provocation coming from the bottom by the erudites who know they have extracted themselves for that bottom by the skin of their teeth. Superficially deep or deeply superficial, both attitudes are two sides of the same coin: a verticalism forcefully imposed by an obsessive cultural imagination.

Verticalism is the easy choice: in scholarship (become the world’s greatest specialist in Lydian coins from the 7th century BC, and to hell with the rest), in architecture (solve social housing by piling thousands of families in insalubrious towers), in politics (become dictatorships and have everyone just follow the leader), in human relations (just obey the boss). But to be horizontal: to accept the image in the mirror and realise it is not distorted – however much we wish it were; to acknowledge that we are not clever all the time or perhaps ever, that we do not know everything, even if – and indeed because – we know one thing very well… even the greatest hedgehog, as Isaiah Berlin showed, was in fact a fox. To become horizontal, in short, that is what, even American scholars, would be better off thinking about.

[1] In the collected volume of his essays, V.Nabokov, Lectures on Russian Literature, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich: 1981.