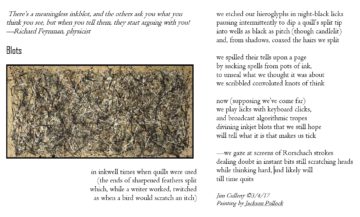

by Joseph Shieber

A recent study in Public Understanding of Science found that

… Republicans and evangelical-identifying individuals perceive more social threat from scientists. Viewing scientists as a group posing a social threat was associated with having less accurate science beliefs, support for excluding scientists from policymaking, and support for retributive actions toward scientists …

One of the co-authors of the study, Ariel Hassell, suggested that the study demonstrates that, “When people position science as something we should be for or against, believe or disbelieve, we lose sight of the fact that scientific research is a process.” She continued:

Often new evidence renders previous knowledge incorrect or irrelevant … Distrust, criticism and debate, when done in good faith, are part of this process and should be engaged with rather than demonized or weaponized. Otherwise, as our study shows, people may begin to see science and scientists as a social or political threat, inhibiting society’s ability to address large scale problems like hunger, disease and climate change.

It strikes me as correct to see this study as offering evidence that it is unhelpful to criticize as irrational those communities that reject scientific consensuses. I’m not sure that a further lesson from the study, however, is to suggest that “science isn’t something to be for or against.” Instead, it would be more useful to find a way to reorient those communities so that being informed about — and being in agreement with — elite scientific opinions would contribute to higher social status. That is, it seems to me that we SHOULD be finding ways to encourage more communities to perceive science as something they should be FOR. (Indeed, only then – as the study itself shows – will they appreciate “the fact that scientific research is a process.”)

I take this to be one of the lessons emerging out of my recently published paper, “An Idle and Most False Imposition: Truth-Seeking vs. Status-Seeking and the Failure of Epistemic Vigilance.” (It’s available as open access article here.) Here’s why. Read more »

One of the easy metaphors, easy because it just feels true, is that life is like a river in its flowing from then to whenever. We are both a leaf floating on it, and the river itself. Boat maybe. Raft more likely. But those who know such things say there is a river beneath the river, the hyporheic flow. “This is the water that moves under the stream, in cobble beds and old sandbars. It edges up the toe slope to the forest, a wide unseen river that flows beneath the eddies and the splash. A deep invisible river, known to its roots and rocks, the water and the land intimate beyond our knowing. It is the hyporheic flow I’m listening for.” The person speaking is Robin

One of the easy metaphors, easy because it just feels true, is that life is like a river in its flowing from then to whenever. We are both a leaf floating on it, and the river itself. Boat maybe. Raft more likely. But those who know such things say there is a river beneath the river, the hyporheic flow. “This is the water that moves under the stream, in cobble beds and old sandbars. It edges up the toe slope to the forest, a wide unseen river that flows beneath the eddies and the splash. A deep invisible river, known to its roots and rocks, the water and the land intimate beyond our knowing. It is the hyporheic flow I’m listening for.” The person speaking is Robin There is a scene near the end of First Reformed, the 2017 film directed by Paul Schrader, where the pastor of a successful megachurch says to the pastor of a small, sparsely attended church:

There is a scene near the end of First Reformed, the 2017 film directed by Paul Schrader, where the pastor of a successful megachurch says to the pastor of a small, sparsely attended church:

Maria Berrio. From the series “In A Time of Drought”.

Maria Berrio. From the series “In A Time of Drought”. The Lede

The Lede 1.

1.

“D — — , I presume, is not altogether a fool, and, if not, must have anticipated these waylayings, as a matter of course.”

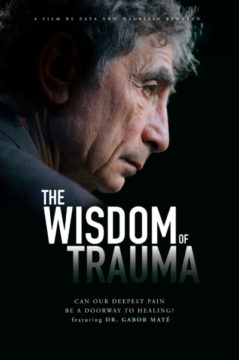

“D — — , I presume, is not altogether a fool, and, if not, must have anticipated these waylayings, as a matter of course.” He received the Order of Canada, profoundly helped many people with addiction on the streets of Vancouver, and is much loved and admired, but some of Dr. Gabor Maté’s claims feel like they don’t hold water. And some claims might actually be dangerous if blindly accepted.

He received the Order of Canada, profoundly helped many people with addiction on the streets of Vancouver, and is much loved and admired, but some of Dr. Gabor Maté’s claims feel like they don’t hold water. And some claims might actually be dangerous if blindly accepted.