by Ashutosh Jogalekar

This is the eighth in a series of essays on the life and times of J. Robert Oppenheimer. All the others can be found here.

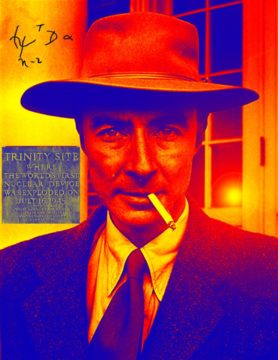

After his shameful security hearing, many of Oppenheimer’s colleagues thought he was a broken man, “like a wounded animal” as one colleague said. But Freeman Dyson, a young physicist who was as perceptive of human nature as anyone, saw it differently: “As far as we were concerned, he was a better director after the hearing than he was before.”

Director of what? Of the “one, true, platonic heaven”, the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, a place where the world’s leading thinkers could think and toil in unfettered surroundings. It was here that Oppenheimer entered the fourth and final act of his life, one that was to thrust him on the national and international stages. There is no doubt that the hearing deeply affected him, but instead of dooming him to a life of obscurity and seclusion, it invested him with a new persona, a new role as a public intellectual in which he performed magnificently. Far from being the end of his life, the hearing signaled a new beginning.

It had been an unpromising start. “Princeton is a madhouse”, Oppenheimer had written to his brother Frank in a 1935 letter, “its solipsistic luminaries shining in separate and helpless desolation.” The institute had been set up by funds from a wealthy brother and sister, Louis and Caroline Bamberger who, just before the depression hit, had fortuitously sold their department store to R. H. Macy’s for $11 million. The philanthropic Bambergers wanted to give back to the community and sought the advice of a leading educator, Abraham Flexner, as to how they should put the money to good use. Flexner dissuaded them from starting a medical school in Newark. Instead he had a novel idea. As an educator he knew the importance of pure, curiosity-driven research that may or may not yield practical dividends. Later in 1939 he wrote an influential article for Harper’s Magazine titled “The Usefulness of Useless Research” in which he laid out his vision.

In that article and to the Bambergers, Flexner pointed out the great benefits to society that had accrued from the exploration of purely academic subjects. A prime example was Maxwell’s investigations of electromagnetic phenomena which had a direct connection with the development of electrical power generation. Flexner also knew that the cost-benefit ratio for nurturing this research was very low, since supporting the careers of outstanding intellects was cheap compared to the abundant fruits of the ideas they might develop, even if such fruits might come intermittently. The only condition for that flowering of creative intellect was to identify the right people and then give them complete freedom to do whatever they wanted. Aware of the anti-Semitism and fascism that was brewing in Europe and the opportunity it would provide to attract Europe’s brightest, in 1930 Flexner convinced the Bambergers to fund an institute of pure, curiosity-based research and study. Thus was born the Institute for Advanced Study.

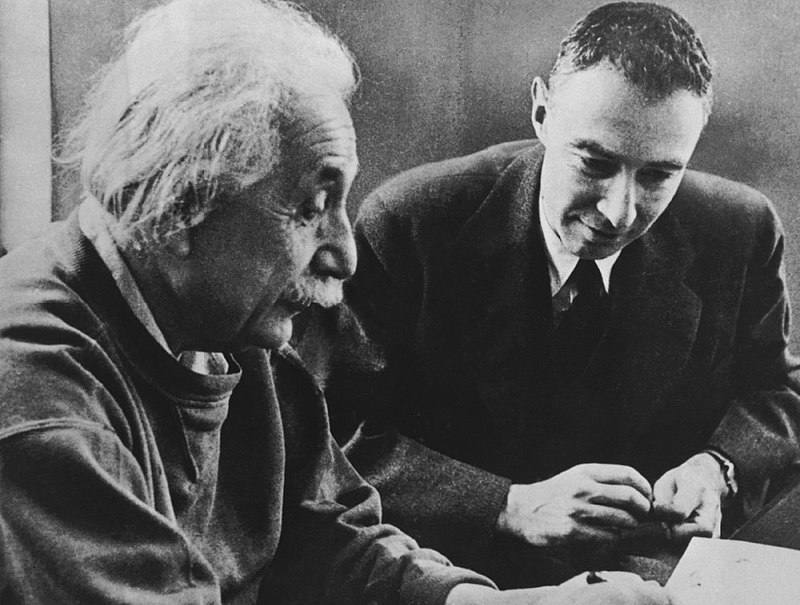

Flexner knew exactly who to populate it with. The European exodus of Jewish scientists was shortly to start after Hitler became chancellor of Germany in 1933, and with it Flexner managed to bag the biggest fish of them all – Albert Einstein. Plagued by an anti-Semitic campaign to discredit him largely spearheaded by the physicist Philipp Lenard, Einstein had seen the writing on the wall earlier than others and was looking for a perch where he could settle. He had seriously considered the California Institute of Technology but he would be required to teach and engage in administrative duties there. Flexner’s plans for an institution where neither of those duties existed and where he would be free to think whatever great thoughts he had was immensely attractive to Einstein. “Ich bin Feuer und Flamme dafur” (“I am fire and flame for that”), he had said. In 1933 Einstein moved for good from Germany – where he had made his home for the past three decades and developed his signal achievement, the general theory of relativity – to the tiny town of Princeton, NJ. “Princeton is wonderful. A quaint and ceremonious village of puny demigods on stilts”, was his first impression. The denizens of the quiet town whose biggest claim to fame had been its university were startled to suddenly start seeing the famous mane of hair bobbing up and down as Einstein walked from his home to work and back. It was in the institute that Einstein was to do the most important piece of work in the second half of his life, an exploration of what we now call quantum entanglement and the EPR paradox. When his colleague Paul Langevin heard that Einstein had accepted Flexner’s offer he prophetically quipped, “The pope of physics has moved and the United States will now become the center of the natural sciences.”

Others followed. In the next few years Flexner secured as permanent members some of the 20th century’s brightest intellects, among them mathematician and polymath John von Neumann, logician Kurt Gödel, mathematician Oswald Veblen and mathematical physicist Hermann Weyl. By the beginning of the war, the institute was firmly ensconced as perhaps the biggest concentration of theoretical intellect in the country. Starting with a $5 million endowment from the Bambergers, it soon acquired a board of rich, influential trustees, including future Oppenheimer nemesis Lewis Strauss. Housed initially in Fine Hall, Princeton University’s mathematics department, the institute soon acquired its own quarters, a stately set of buildings on land next to the Princeton battlefield, home of the Battle of Princeton which was the first conflict George Washington had actually won. A lake filled with fish and snapping turtles bordered leafy woods where visitors could walk and where Veblen who was an avid outdoorsman could chop wood. The princely sums the members commanded – Einstein who had asked for a modest $5000 when hired was paid $15,000 – led the institute to be called the “Institute for Advanced Salaries”. Its better than average lunch and dinner menu – there was a dedicated cafeteria – led to students from neighboring Princeton University who were on shoestring budgets calling it the “Institute for Advanced Lunches”.

As much as Flexner had been influential in hiring the first few members of the institute, things did not go well when he tried to micromanage his hires; the mathematicians especially stood up in revolt. He resigned in 1939, handing the reins to Frank Aydelotte who shepherded the place through World War 2, a time in which many members like von Neumann and Veblen left to do war work. In 1947 the institute trustees were looking for a new director and Oppenheimer shot to the top of a short list of candidates. The reasons were obvious; having led the successful effort to built the atomic bomb two years before, he was a household name and had the “name brand recognition”, and he was widely known not just for his scientific success but for his remarkably wide-ranging knowledge of the humanities. In addition he could be an eloquent spokesman for causes he believed in and was known for mesmerizing small groups of audiences. An institute trustee who interviewed Oppenheimer found him to have a “quickness in repartee that gives him great force”. “He is only forty-three years of age”, noted the trustee, “and despite his preoccupation with atomic physics, has kept up his Latin and Greek, is widely read in general history and collects pictures. He is altogether an extraordinary combination of science and the humanities.”

Lewis Strauss offered the directorship to Oppenheimer when he felt him out for the chairmanship of the General Advisory Committee of the Atomic Energy Commission. Oppenheimer was unsure, still enjoying sunny California, the place where he had made his name and which he considered home. But he must have seen the appeal, not just in the opportunity the place would provide for him to indulge his wide interests but for the proximity it would offer to the centers of power in Washington which increasingly beckoned him. The decision was made for him when he heard the news of his appointment while driving over the bridge from Oakland to San Francisco one evening – “I guess that settles it, then”, he said to Kitty. He would be hired at a salary of $20,000 and would be given rent-free accommodations in Olden Manor, a handsome three-floor house whose wings had been used as a makeshift hospital during the Battle of Princeton. Robert moved with Kitty and their son and daughter, Peter and Toni (Katherine), to Princeton in the fall of 1947.

When Strauss was looking around for a director, he had asked the members what kind of a man they wanted. Einstein had replied, “Ah, that I can do gladly. You should look for a very quiet man who will not disturb people who are trying to think.” The institute was a scholarly paradise, and Oppenheimer as a scholar’s scholar was in many ways the ideal choice to lead it. But if the members thought they were getting a “very quiet man” who would not try to topple the apple cart, they were mistaken. It was precisely Oppenheimer’s breadth of knowledge and interests that rubbed some of them the wrong way. Foremost among this group were the mathematicians who were opinionated and vocal and dominated the faculty. Mathematics is the purest, most untarnished, most theoretical discipline, and it was mathematicians who Flexner had lured to the place as his first hires. The mathematicians assumed that most appointments would continue to be in highly mathematical disciplines like theoretical physics.

But Oppenheimer wanted to greatly expand the mandate of the institute, and along with mathematicians and physicists, he started inviting historians, archeologists, poets, writers and psychologists for short terms. He had himself assigned a handsome discretionary director’s fund – which was tantamount to being like a kid in a candy store who could order whatever he wanted. Among the intellectuals and scholars that Oppenheimer invited over the next few years were his childhood friends Harold Cherniss and Francis Fergusson, the archaeologist Homer Thompson, the child psychologist David Levy, the historian Arnold Toynbee and the poet T. S. Eliot. The diplomat and writer George Kennan was appointed as a permanent member, against the protests of members who thought Kennan was not scholarly enough (Kennan would later write a series of elegant, prizewinning books on American foreign policy and diplomacy and became an admiring friend of Oppenheimer’s). It was at the institute that Fergusson wrote a book titled “The Idea of a Theater” which has been called the most famous book on drama written by an American. Oppenheimer was particularly delighted to invite Eliot, one of the greatest literary talents of the 20th century – Eliot’s “The Wasteland” had had a foundational impact on him as a young man – and he hoped he would write something that rivaled his previous great works. Eliot’s fame further soared when it was announced during his time at the institute that he had won the Nobel Prize for Literature. But Oppenheimer was disappointed when all Eliot wrote during his tenure was “The Cocktail Party” which Oppenheimer considered the worst thing the poet had ever written.

One anecdote that displays better than anything else Oppenheimer’s astonishing grasp of disciplines other than his own deserves to be mentioned. An English professor and administrator named Lansing Hammond was in charge of selecting fellows for the Commonwealth Fellowship that would send promising young men and women from England to the United States for study; it was this fellowship that had supported the young Freeman Dyson. Hammond had requested an hour of Oppenheimer’s time for help selecting fellows in mathematics and physics. Oppenheimer unsurprisingly had an intimate knowledge of the best professors and graduate schools in the country for these fields. Just as Hammond was leaving, Oppenheimer asked him if he could also take a look at some of the applications in the humanities. Here are Hammond’s evocative words relaying his unforgettable experience:

“As I was gathering up my papers, feeling I’d already taken up too much of the great man’s time, he asked gently: “If you have a few minutes you can spare, I’d be interested in looking at some of your applications in other fields, to see what this year’s group of young Britons are interested in pursuing over here?” I took him at his word, and was completely overwhelmed by what ensued: “Umm—indigenous American music—Roy Harris is just the person for him, he’ll take an interest in his program. Roy was at Stanford last year but he’s just moved to Peabody Teachers’ College in Nashville. Social psychology, he gives Michigan as first choice—Umm—he wants a general, overall experience. At Michigan he’s likely to be put on a team and would learn a lot about one aspect. I’d suggest looking into Vanderbilt; smaller numbers; he’d have a better opportunity of getting what he wants.” (The candidate was persuaded to try Vanderbilt for one term, with the option of transferring to Michigan if he wasn’t satisfied. He spent two years at Vanderbilt, with profit and enthusiasm.) “Symbolic logic, that’s Harvard, Princeton, Chicago or Berkeley; Let’s see where he wants to put the emphasis. Ha! Your field, 18th-century English Lit. Yale is an obvious choice, but don’t rule out Bate at Harvard, he’s a youngster but a person to be reckoned with.” (My field, and I’d not yet even heard of Bate, but I took pains, the next time I was in Cambridge, to meet and talk with him.)

We spent at least an hour, thumbing through all of the sixty applications. Robert Oppenheimer knew what he was talking about. He pleaded ignorance about two or three esoteric programs. Every positive comment or recommendation was right on target. And so, when it finally came time to leave, I couldn’t resist saying that if I could only bribe him, once a year, to repeat what he’d just done, it would save me months of sweating. He really grinned at that. “That wouldn’t be fair to you, Dr. Hammond. It would take away the satisfaction and excitement of talking with lots of other people and finding out for yourself.” I left, walking on air, head abuzz, most of my problems solved. Never before, never since have I talked with such a man. No suggestion of trying to impress. No need to. Robert Oppenheimer’s was just genuine interest in all fields of the intellect; a fantastically up-to-date knowledge of what was going on in US graduate schools and research centers; an intuitive understanding of where a given person with definite interests would best fit in; and taking pleasure in being of help to someone who badly needed it.”

Most of this did not matter to the mathematicians. They resented the fact that Oppenheimer was stacking up the faculty with non-mathematicians and assorted humanists. It also did not help that he was supportive of a groundbreaking project to build a computer that was spearheaded by von Neumann; the mathematicians considered that a blasphemous encroachment of engineering into pure thought (when after von Neumann’s death the mathematicians voted to terminate the computer project, Dyson said that “the snobs had their revenge”). At one point, after having an argument with the topologist Deane Montgomery about faculty appointments, Oppenheimer snapped back, “You, Deane, are the most arrogant, bull-headed son-of-a-bitch I have ever met.” Montgomery’s colleagues responded in kind. Algebraic geometer André Weil, brother of the noted philosopher Simone Weil, put the blame on what he thought were unfulfilled ambitions: “Oppenheimer was a wholly frustrated personality…he was essentially frustrated because he wanted to be Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr, and he wasn’t.”

Weil’s quip provides a reference point for two divergent comparisons. Unlike with Bohr, Oppenheimer’s relationship with Einstein was cordial but not close; he once somewhat unkindly called the physicist “a lighthouse, not a beacon”. Einstein and Oppenheimer were on opposite sides politically – Einstein could never imagine himself being in the political mainstream the way Oppenheimer was – but also scientifically because of Einstein’s famous dissatisfaction with quantum mechanics and alienation from mainstream research in particle physics. Yet after Einstein’s death Oppenheimer was to write about the great man that he was a “twentieth century Ecclesiastes” and a man “wholly without worldliness”.

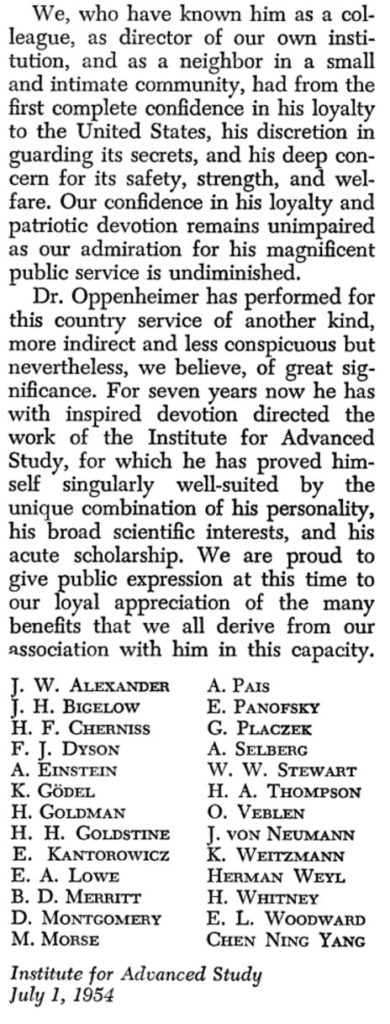

But whatever the relations between Oppenheimer and Einstein and the other members of the institute, they spoke out against his shameful security hearing with one voice. When Strauss tried to add to the ignominy of having Oppenheimer’s security clearance taken away by also trying to get him fired as institute director, they took a stand. Very shortly after the hearing, twenty-six members collectively published a letter in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, testifying to both Oppenheimer’s loyalty and his value as institute director; the signatories included many of the mathematicians he occasionally seemed to be at war with. Strauss could not have his way and Oppenheimer remained director until his death in 1967.

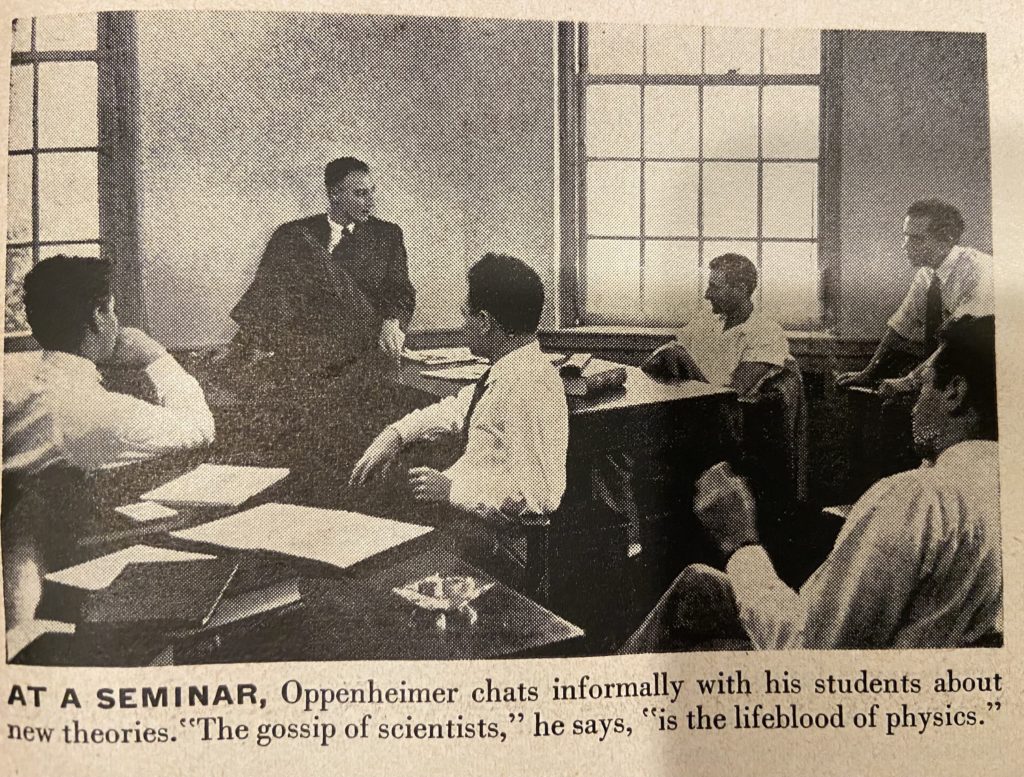

As important as Oppenheimer’s appointments in the humanities were in expanding the institute’s allure, physics came first. At the institute Oppenheimer created the same concentration of talent that he had created at Los Alamos, making the institute the most distinguished place in the world for doing mathematics and theoretical physics – a reputation that it continues to have. Physicists such as Freeman Dyson and Abraham Pais were appointed as permanent members and others like Chen Ning Yang, Tsung Dao Lee, Murray Gell-Mann and others who became some of the most successful physicists of the 20th century were visiting members. Oppenheimer’s old colleagues and friends including Niels Bohr, Paul Dirac and Wolfgang Pauli visited multiple times. Einstein, Gödel and von Neumann were longtime fixtures. There is hardly a famous theoretical physicist from the second half of the 20th century who does not have some kind of association with the institute. The rarefied atmosphere is captured by Pais, a writer of uncommon talent in both physics and letters: “This is an unreal place”, he wrote in 1948, shortly after being hired by Oppenheimer. “Bohr comes to my office to talk, I look out of the window and see Einstein walking home with his assistant. Two offices away sits Dirac. Downstairs sits Oppenheimer”.

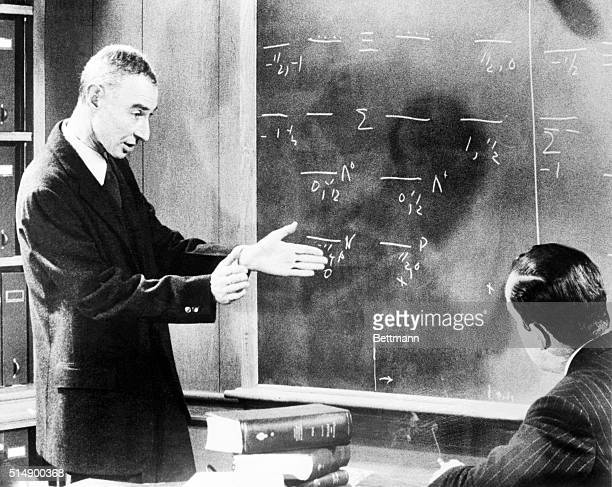

Oppie ruled this roost with the same sure touch, authority and wisdom of a mother hen as he had his scientific children at Berkeley. It was especially notable since after the war, he hardly did a piece of physics research himself; after 1950 he never published a scientific paper. Some of the same qualities that had kept him from achieving his fullest potential before the war now interfered, although the real reason was that his government duties and affinity for the centers of power distracted him and kept him away from the institute too much.

Murray Gell-Mann perspicaciously observed:

“He didn’t have Sitzfleisch. Perseverance, the Germans call it Sitzfleisch, ‘sitting flesh’, when you sit on a chair. As far as I know, he never wrote a long paper or did a long calculation, anything of that kind. He didn’t have patience for that; his own work consisted of little aperçus, but quite brilliant ones. He inspired people to do things, and his influence was fantastic.”

Dyson astutely saw his great strengths: “He had a talent for self-dramatization, an ability to project to his audience an image larger than life, to bestride the world as if it were a stage.” As other events in his life showed, this ability could get him into trouble. But in the world of physics it glowed.

Oppenheimer’s influence was on full display as physicists geared up after the war to pick up the pieces and finish the problems that had kept them busy before radar and atomic bombs diverted them. Some of the thorniest problems emerged from Oppenheimer’s own work. In 1930, Oppenheimer’s paper titled “Notes on the Theory of the Interaction of Field and Matter” had pointed out that when physicists tried to do something as simple as accurately calculate the energy levels of an electron in a hydrogen atom, they arrived at a nonsensical answer of infinity. The calculation essentially blew up at the origin of the electron’s location. Throughout the 1930s various physicists, included many of Oppenheimer’s students, had tried to make headway into the problem without much success. Now during the war, one of Oppenheimer’s students, Willis Lamb, had found using precision microwave spectroscopic techniques that there was a tiny difference between the energies of an electron in a hydrogen atom in two states that could not be explained by Dirac’s successful theory of the electron.

In June 1947, 24 physicists converged on the small island of Shelter Island near Long Island with a view to addressing Lamb’s observation – called the Lamb Shift. The lineup included a who’s who of 20th century physicists ranging from Richard Feynman and Julian Schwinger to John Wheeler and John von Neumann. But it was clear that the intellectual leader was Oppenheimer. Abraham Pais recalls that the bus carrying the physicists which was making its way slowly to the conference was, at one point, suddenly waved through red lights with police sirens. The physicists were perplexed until they found out that the arrangement had been made by the grateful president of a local chamber of commerce who had been stationed as a soldier off the coast of Japan, ready for a bloody invasion, when the bomb was dropped and the war ended; the president treated the scientists to a sumptuous dinner before sending them on their way. The episode indicated the high esteem and virtual awe with which physicists were regarded at the end of the war.

At the conference itself, Oppenheimer’s undisputed leadership was clear. The official chairman of the conference, a physicist named Karl Darrow, attests to Oppenheimer’s performance:

“As the conference went on, the ascendancy of Oppenheimer became more evident – the analysis (often caustic) of nearly every argument, that magnificent English never marred by hesitation or groping for words (I have never heard ‘catharsis’ used in a discourse on physics, or the clever word ‘mesoniferous’ which is probably Oppenheimer’s invention), the dry humor, the perpetually-recurring comment that one idea or another (including some of his own) was certainly wrong, and the respect with which he was heard.”

The same Oppenheimer who used to hold his students and colleagues in thrall at Berkeley and Los Alamos continued to do so. Even if he was not doing research himself he was on top of everything, and it was clear that the physics community continued to regard him as their intellectual leader, a man who understood the excitement and mystique of the field better than anyone else and who would show them the right direction.

Oppenheimer’s public fame became apparent after the conference when he and his colleagues were being flown from Shelter Island to Boston where Oppenheimer was to receive an honorary degree at Harvard. Bad weather forced the plane to make an unauthorized landing at the New London Coast Guard station in Connecticut. The enraged officer was about to arrest the scientists for illegally trespassing when Oppenheimer stepped out and extended his hand, saying, “I am Oppenheimer”. The astonished officer retorted, “The Oppenheimer??”, to which Robert replied, “An Oppenheimer.” Having a celebrity on his hands, the officer extended a warm welcome to the physicists, treated them to refreshments and escorted them under military escort to the train station for boarding a train to Boston.

But even Oppenheimer, a man known for seeing many corners ahead of others, could make mistakes. One became clear when Freeman Dyson, a promising British-born mathematical physicist who he had recruited to the Institute was working out a revolutionary new meld of the theory called quantum electrodynamics that patched up apparent divergences between the ideas of Schwinger and Feynman. He found out that Oppenheimer considered the whole program that he, Feynman and Schwinger were working on to be fundamentally on the wrong track. Dyson braced himself for presenting his theory in a series of seminars. Oppenheimer was notoriously rude and impatient at these presentations, often cutting off speakers or telling them that they were speaking nonsense. This was indeed the reception that Dyson received. He was brought to despair, and it was only when his old mentor and Oppenheimer’s old colleague Hans Bethe came down from Cornell University and intervened that Oppenheimer relented. Without explicitly conceding, Dyson found a note in his mailbox the next morning: “Nolo contendere” (“I do not wish to contend.”). As he did at Berkeley, Oppenheimer seemed to sense what the current “taste” in physics was, but while his assessment was usually right, he missed important cues. For Dyson, his most important mistake was in dismissing his own 1939 paper on black holes, thinking it to be too applied and the province of second-rate minds. In retrospect it can be seen to be one of the seminal papers in 20th century physics, and it is very likely that he would have won the Nobel Prize for it had he lived long enough to see the experimental evidence for these exotic objects mount.

Life at Olden Manor was otherwise bucolic. The alcohol flowed so freely that onlookers jokingly referred to the place as “Bourbon Manor”. But under the tranquil, gay exterior lay troubled waters. It would not be an exaggeration to say that Oppenheimer’s marriage and family life were less than joyful. Kitty Oppenheimer could have been a talented scientist in her own regard, but typical of women of those times she had to take a backseat because of her husband’s high-profile career. Kitty nevertheless ran Olden Manor with a sure hand and was an excellent cook and host. But she had a serious drinking problem, one that had already manifested itself at Los Alamos. And she had acquired the same sharp tongue that her husband had, occasionally displaying casual cruelty to colleagues and friends with her cutting remarks; Pais harshly called her the most despicable woman he had ever known. Nevertheless, she was a rock for Robert, shielding him from publicity and the media, playing a role similar to what Einstein’s wife Elsa played in his life. While she and her husband may not have exactly had a successful marriage, they were what Pais calls co-dependents, relying for better or worse on each other for life’s essentials.

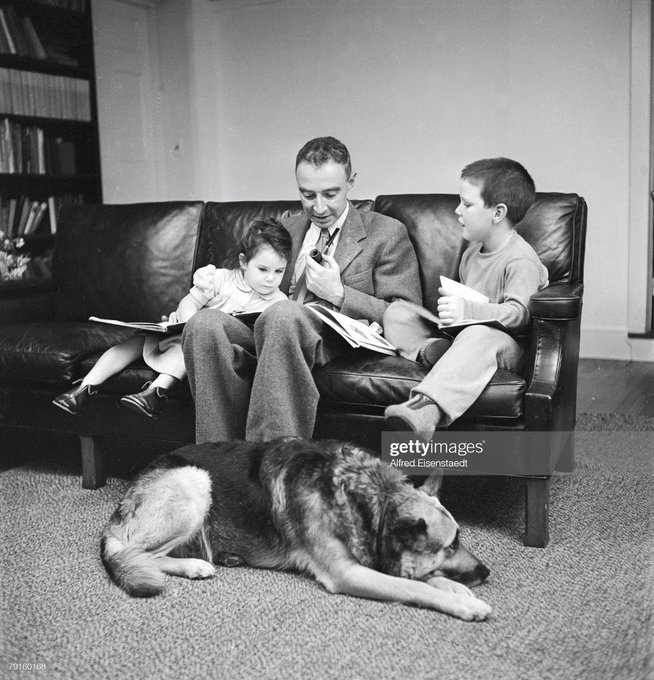

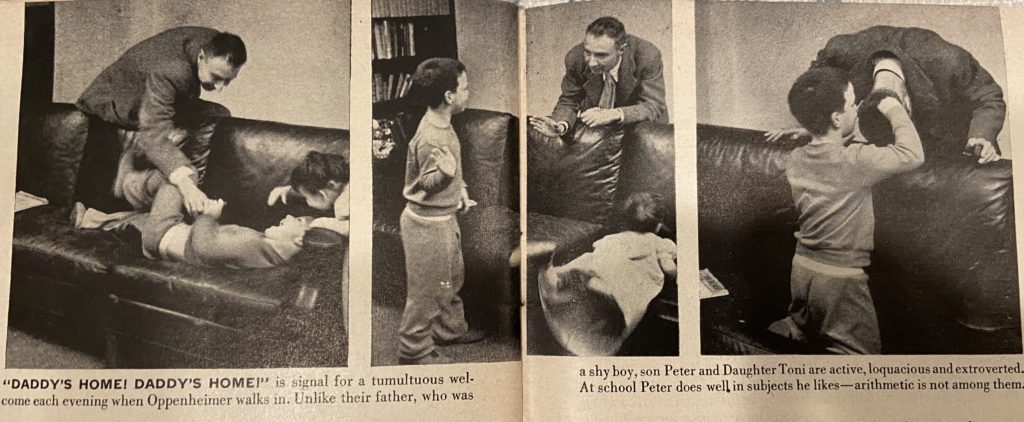

A spread in Life magazine in 1949 showed snapshots of a typical, happy family life: Oppenheimer reading to Toni and Peter with a German shepherd lounging on the floor; botanist Kitty tending to plants in a greenhouse; Robert horsing around with Peter.

But Robert and Kitty’s relations with both Peter and Toni were strained. The children had to suffer the challenges of being in the shadow of their famous father and Robert left much of the childcare and housework to Kitty. In his dealings with his children, Oppenheimer seems to have fit a rather typical mold of a brilliant intellectual who had trouble adjusting to parental relationships.

Toni was a relatively cheerful child but Peter was more sensitive and easily hurt by what seemed at times like his parents’ demanding expectations. Once when he was grown up, Robert refused to take him on a family vacation to Europe because he had failed to get into Princeton for college. But if Robert was a strict parent, Kitty seems to have been worse, harshly chiding him over everything from his weight to his grades. Robert’s security hearing also seems to have had an emotional impact on Peter; following its outcome, the 13-year-old angrily wrote on a chalkboard on his room, “The American Government is unfair to accuse Certain People that I know of being unfair to them. Since this is true, I think that Certain People, and may I say, only Certain People in the U.S. Government, should go to HELL.” Peter relocated West soon after high school and intermittently kept in touch with his parents. Now 82, he shuns publicity and lives in New Mexico, having lived for some time in the old Oppenheimer cabin, Perro Caliente.

Toni, after years of dutifully listening to her mother and dealing with her smoking and drinking, also rebelled as a teenager. She was also deeply affected by the hearing. She worked for some time as a translator but had difficulty finding jobs because the security clearance she needed necessitated bringing up facts about the ugly security hearing. After two failed marriages, she committed suicide on the island of Saint John where the Oppenheimers occasionally lived in the later years of their life. She was 32.

After his hearing, Oppenheimer was often seen as a martyr to the cause of liberal science and freedom. He did not agree with his chosen role and certainly did not regret building the bomb. A particular misunderstanding came from a physics lecture at MIT in 1947 in which Oppenheimer chose to insert a colorful quote that he has become famous for: “In some sort of crude sense which no vulgarity, no humor, no overstatement can quite extinguish, the physicists have known sin; and this is a knowledge which they cannot lose.” The quote has been misunderstood to mean that ‘the sin’ referred to building the bomb, but that was not what Oppenheimer meant; rather he meant that he felt it a pity that the pure discipline of physics which he loved could logically culminate in a weapon of mass destruction. Freeman Dyson felt that the quote was referring to a feeling of guilt, guilt not in building it but in having a great time while doing it.

Close to the end of his life, his former student David Bohm wrote him a letter saying that he felt disturbed about what he thought were feelings of guilt that Oppenheimer had expressed in public. Oppenheimer promptly replied, saying, “What I have never done is express regret for what I did and could at Los Alamos. In fact, on various and recurrent occasions, I have reaffirmed my sense that, with all the black and white, that was something I did not regret.” When the playwright Heinar Kipphardt wrote a play in 1964 titled “In the Matter of J. Oppenheimer” in which he cast Oppenheimer as a tragic, fallen hero, Oppenheimer quipped, “The whole damn thing [the security hearing] was a farce and these people are trying to make a tragedy out of it.” Knowing the horrific arms buildup that had developed in the previous decade and the way political solutions had sometimes turned into black comedy because of the ignorance of men in power, he knew exactly what farce he was talking about.

Mostly Oppenheimer spent the post-hearing years being the kind of philosopher-scientist-statesman that his hero Niels Bohr had been. The reason it’s hard to buy the assessment that he was a broken man is because he succeeded spectacularly at this. Time after time he gave lectures on science and on man and his condition to packed audiences numbering in the hundreds and thousands. He was interviewed several times, most notably by the well-known journalist Edward Murrow. Thanks to the Internet, many of these talks and interviews are now accessible on YouTube. I have gathered together a compilation. One of them was at UCLA in 1964 and is dedicated to Niels Bohr. Another is a 1962 technical talk on symmetry in physics. Yet another is a reflection on analogy in science. A speech at the Princeton Theological Seminary is particularly notable for the Q&A session at the end. In all these talks Oppenheimer is characteristically eloquent and wide-ranging but also spirited and humorous, often answering questions with endearing sarcasm and wit. There is no hand-wringing and nothing of the depressed confessions or resentment that you would imagine from someone who had been through what he had. The talks show that Oppenheimer was enjoying his role as a public intellectual and continued – unlike his enemies Lewis Strauss and Edward Teller – to be a hugely popular figure who was revered as a speaker, thinker and all-around wise man.

There were some themes that resonated through his talks. Many of them are collected together in two volumes, “Science and the Common Understanding (1954)” based on the Reith Lectures he gave on the BBC and “The Open Mind”, based on talks at various venues given between 1946 and 1955. The talks cover a wide range of territory, from the grave problems posed by atomic weapons to science education and the history of science to the deep mysteries of physics. But one unifying theme that emerges constantly from these talks is that of open inquiry, of freedom of communication, of the tentative feeling of hope and truth that scientists have when they work at the frontier, of the constant allowance of making an error. In a 1950 interview he said, “There must be no barriers to freedom of inquiry. There is no place for dogma in science. The scientist is free, and must be free to ask any question, to doubt any assertion, to seek for any evidence, to correct any errors.”

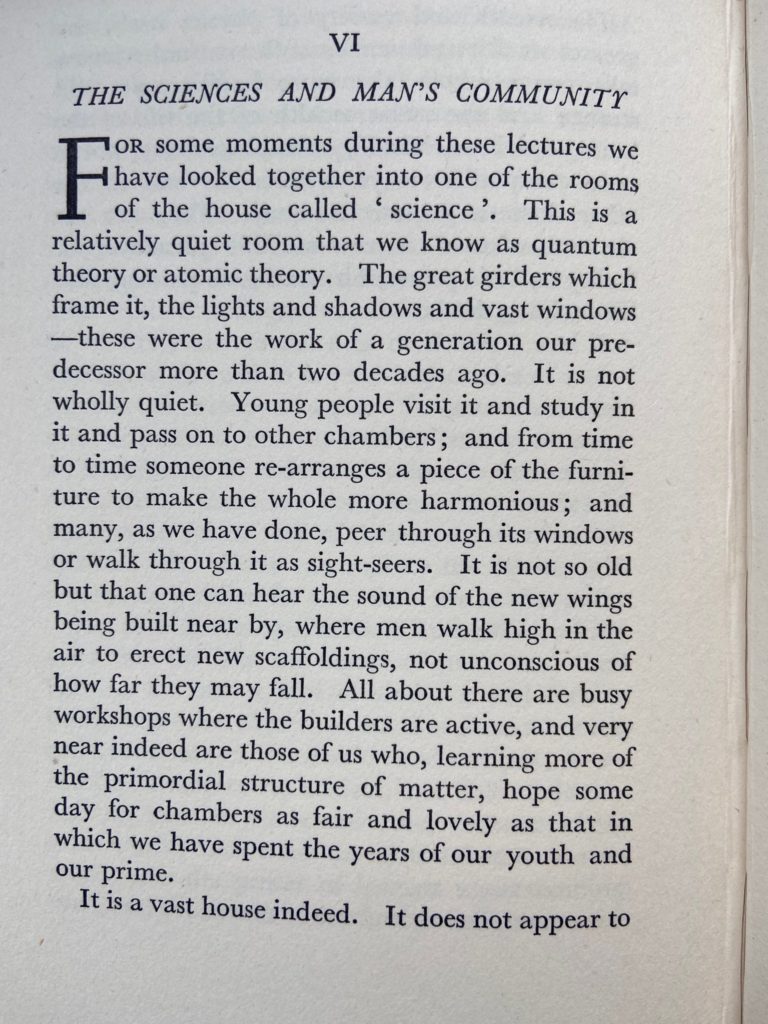

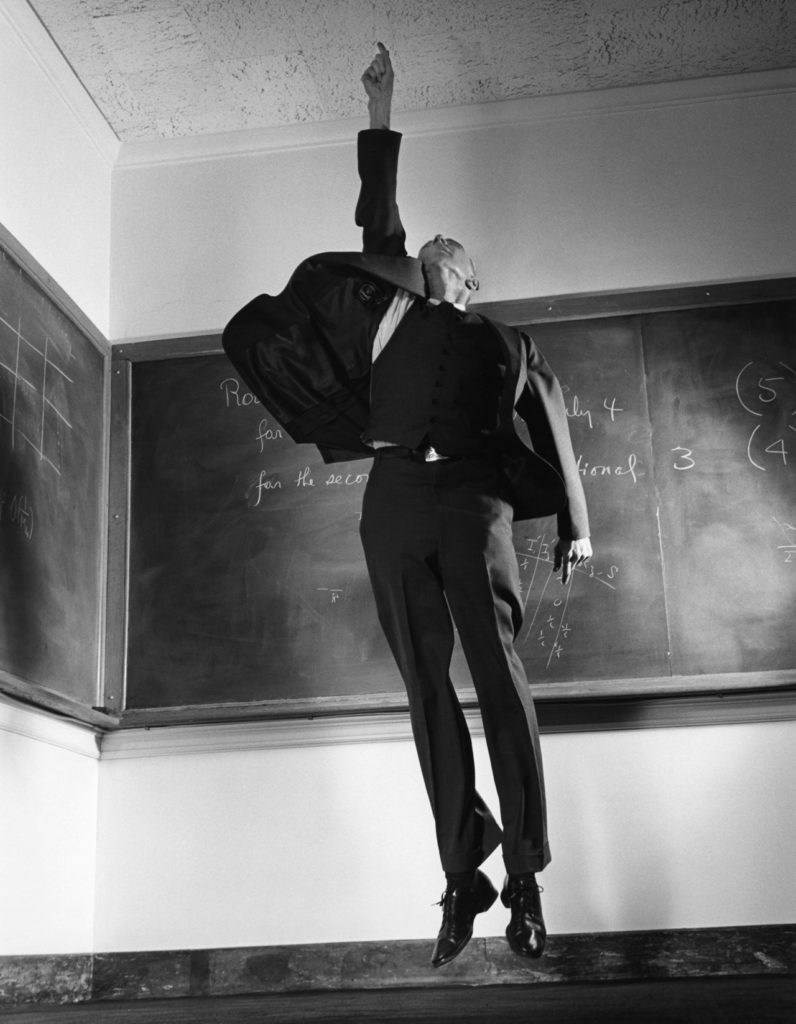

Many beautiful passages from Oppenheimer’s speeches and writings can be quoted. For me perhaps the most beautiful, and one worth quoting at length, is an excerpt from a passage from “Science and the Common Understanding” that sees science as a house whose construction is always in progress. I know of no other piece of writing that conveys so wonderfully the dynamic, open, hesitant, exciting process of doing science.

From the author’s copy of “Science and the Common Understanding”.

Oppenheimer’s political rehabilitation began in the late 1950s after his friends and colleagues, men sympathetic to him like McGeorge Bundy and Arthur Schlesinger, had made sure that Lewis Strauss would not grow in power. After Kennedy became president and a new liberal administration was in place, some of his scientific friends on the President’s Science Advisory Committee (PSAC) sent out feelers to see if his security clearance could be re-instituted. But Oppenheimer had no desire to dredge up all the details of his background and Bundy who was Kennedy’s National Security Advisor also did not want to revisit the case. But after Kennedy became president, Bundy made sure that Oppenheimer was invited to an elite 1962 dinner with the president featuring the era’s leading scientists, writers and other intellectuals; it was at this dinner that Kennedy famously said that “I think this is the most extraordinary collection of talent, of human knowledge, that has ever been gathered together at the White House, with the possible exception of when Thomas Jefferson dined alone.”

In 1963, Kennedy announced that Oppenheimer would receive that year’s prestigious Fermi Award which had been created in 1954 to honor his old colleague Enrico Fermi. Strauss fumed from the sidelines; Teller, to perhaps assuage his conscience, sent Oppenheimer a congratulatory note. But Kennedy was assassinated before he could present the award, so it fell to Lyndon Johnson to do it. In an elegant ceremony which Oppenheimer enjoyed, Johnson presented the physicist with a certificate and a gold medal with the likeness of Fermi (the award also came with a $100,000 check – LBJ joked, “You may observe that she [Kitty] got hold of the check!”). Knowing the peculiar history and tortuous path which had led him to this moment, Oppenheimer thanked the president and said, “I think it’s just possible, Mr. President, that it has taken some charity and some courage for you to make this award today. That would seem to be a good augury for all our futures.”

Seemingly untouched by the turmoil of the 60s, or perhaps because he no longer wanted to court controversy, Oppenheimer continued to write and speak on science and philosophy. He and his family bought property in Saint John, one of the Virgin Islands in the brilliant blue Caribbean Sea. His neighbors there soon became aware that a celebrity was in their midst, and for some time Robert and Kitty entertained an assorted cast of characters that would probably be reminiscent of the Berkeley of recent decades; painters, writers and itinerant visitors who he would invite on the beach or into the home that he had designed. Perhaps sensing that he should take it easy, he announced in 1965 that he would soon resign as director from the institute; he had been leading the august institution for seventeen years and had built it to great heights, and with a mandatory retirement age approaching, he thought that he should better hand over the reins to fresh blood.

But in February 1966, complaining of a sore throat, Oppenheimer went to his doctor and found that he had throat cancer. The decades of chain smoking had finally caught up. He underwent a painful operation on his larynx and followed it up with radiation treatment in New York. For some time it seemed like the cancer was regressing, but by October that year it had spread to his palate, his Eustachian tube and the base of his tongue; whatever respite the radiation treatments was bringing seemed to quickly abate. Even relative to his always frail frame he lost weight and had to be put on a liquid and protein powder diet. But he never complained, leaving visitors, friends and colleagues marveling at his forbearance and doggedness. Old confidants like David Lilienthal and Francis Fergusson came to visit; so did his brother Frank. A particularly moving scene transpired when Louis Fischer, a friend who was a journalist and biographer of figures like Gandhi and Lenin, called on him. The two sat in the living room largely in silence as Robert struggled to speak. When Fischer got up to leave he found a pack of cigarettes lying on the stairs. As he bent down to pick it up, he saw that the weakened Robert had appeared at his side with his lighter out and open, the remnant of an unfailing habit he had since his younger years of lighting people’s cigarettes and pipes for them.

Ever the philosopher and actor, Oppenheimer faced an early demise with grace and unflinching acceptance. Freeman Dyson saw his “spirit grow stronger as his bodily powers declined.” “I saw then”, Dyson said, “what his friends had seen at Los Alamos, a man carrying a crushing burden and still doing his job with such style and good humor that all of us around him felt uplifted by his example.” Kitty, desperate and at a loss to know what was the right thing to do to make Robert feel at peace, asked Dyson if he wanted to collaborate with his director on a piece of physics. Dyson quietly told Kitty that he would rather sit with Robert and hold his hand, thinking that “it was too late to cure his anguish with equations.”

On February 15, 1967, Oppenheimer came to a faculty meeting to judge a box full of applications for the new year. Knowing that he would not be around to meet the new fellows, he nevertheless came prepared to minutely discuss the pros and cons of each applicant. “We should say yes to Weinstein, he’s good”, were the last words Dyson heard him say. Two days later on February 17, Francis Fergusson came to visit. In many ways Fergusson was Robert’s last and most important link to the past, having witnessed his adolescence and coming of age at Harvard and in Europe. By now the emaciated physicist weighed less than a hundred pounds. Fergusson soon realized that asking for any more effort on his friend’s part would be an imposition. “I walked him into his bedroom and left him there”, Fergusson said, “and the next day I heard that he died.” Robert Oppenheimer died in his sleep at 10:40 PM on Saturday, February 18, 1967. He now belonged to the age that he had done so much to create.

Condolences and reminiscences came from all around the world; even Strauss sent a letter to Kitty. David Lilienthal told the New York Times that the world had lost “a genius who had brought together science and poetry.” Senator J. William Fulbright reminded everyone, “Let us remember what his special genius did for us; let us also remember what we did to him.” On a bitterly cold morning on February 25, 600 people lined up in Alexander Hall on the Princeton University campus. Hans Bethe, Henry Smyth – the one principled soul who had voted to re-institute Oppenheimer’s security clearance after the hearing – and George Kennan delivered brief eulogies. Kennan commented particularly on Oppenheimer’s “deep yearning for friendship, for companionship, for the warmth and richness of human communication.” But a particularly telling remark was offered by clear-headed Isidor Rabi, a man who knew Oppenheimer as well as anyone else, at a memorial service organized by the American Physical Society in April. “In Oppenheimer”, said Rabi, “the element of earthiness was feeble. Yet it was essentially this spiritual quality, this refinement as expressed in speech and manner, that was the basis of his charisma. He never expressed himself completely. He always left a feeling that there were depths of sensibility and insight not yet revealed. These may be the qualities of the born leader who seems to have reserves of uncommitted strength.”

When Oppenheimer had been director at Los Alamos, one of the few escapes for him was an excursion to the adobe house of Edith Warner, a kindly woman who ran what she described as a tea room for tourists that was located about twenty miles down the winding road to the secret lab. Her house was spare and simply adorned and Oppenheimer and his colleagues often made it down there for dinner; the place was a little bit of an exclusive retreat where Oppenheimer would take visitors like Niels Bohr who was visiting Los Alamos using his secret alias, Nicholas Baker.

Robert later told Edith that he always thought that the “spirit of Bohr had been alive” in her little house. After she read Oppenheimer’s farewell speech from November 1945, Edith wrote a letter to him. “Dear Mr. Opp”, it said, “It seems almost as though you were pacing my kitchen, talking half to yourself and half to me. And from it came the conviction of what I’ve felt a number of times – you have, in lesser degree, that quality which radiates from Mr. Baker. It has seemed to me in these past few months that it is a power as little known as atomic energy…I think of you both, hopefully, as the song of the river comes from the canyon, and the need of the world reaches even this quiet spot.”

I would like to think that as the end approached, Robert Oppenheimer was thinking of that quiet spot, listening to the song of the river that came from his beloved canyon.

Sources:

- Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin, “American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer”, 2005

- Ray Monk, “Robert Oppenheimer: A Life Inside the Center”, 2013

- Abraham Pais and Robert Crease, “J. Robert Oppenheimer: A Life”, 2006

- Post: Big Things Come in Little Packages: “How Willis Lamb’s Tiny Measurement Revolutionized 20th Century Physics”, 2016

- J. Robert Oppenheimer, “Science and the Common Understanding”, 1954

- Freeman Dyson, “Disturbing the Universe”, 1979

- Freeman Dyson, “Oppenheimer as Scientist, Administrator and Poet”, in “The Scientist as Rebel”, 2006

- George Dyson, “Turing’s Cathedral: The Origins of the Digital Universe”, 2012

- I. I. Rabi, Robert Serber, Victor Weisskopf, Abraham Pais and Glenn T. Seaborg, “Oppenheimer”, 1969

- Mark Wolverton, “A Life in Twilight: The Final Years of J. Robert Oppenheimer”, 2008