by Rafaël Newman

“D — — , I presume, is not altogether a fool, and, if not, must have anticipated these waylayings, as a matter of course.”

“D — — , I presume, is not altogether a fool, and, if not, must have anticipated these waylayings, as a matter of course.”

“Not altogether a fool,” said G., “but then he is a poet, which I take to be only one remove from a fool.”

“True,” said Dupin, after a long and thoughtful whiff from his meerschaum, “although I have been guilty of certain doggerel myself.”

—Edgar Allan Poe, “The Purloined Letter”

On the eve of their wedding day, on September 12, 1840, Robert Schumann presented Clara Wieck with a collection of 26 songs of his own composition, settings of poems by Goethe, Byron, Heine, Burns, and others. Arranged in four fascicles, the songs foreground literary works in which the speaking voice seems by turns male and female, at least by conventional codification. The poems’ themes range widely, including typical romantic topoi, such as flowers, the Scottish Highlands, and forbidden love affairs, but also drinking songs, ribaldry, and mock rhetorical argument. The very diversity of the selections suggests some definite, if eclectic and highly personal organizing principle had ordained them. And indeed, Schumann’s Myrthen opus 25, although named innocently enough for the myrtles traditionally carried by brides in the 19th century, was more than simply a Brautgeschenk or “bridal gift,” more than merely a pretty, arbitrarily assembled anthology (a term whose etymological roots are similarly floral), since it also celebrates the couple’s triumph over odds both familial and legal—Clara’s father had been resolutely opposed to the marriage, and she had had to win the right to marry Robert at court—as well as the union of two gifted and epochal musical artists.

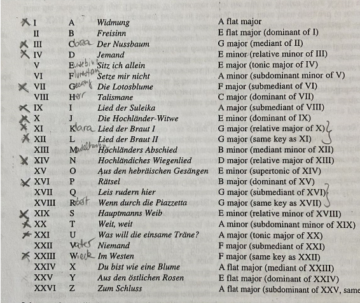

Now, there is indeed a possible structural determinant of the selections for the cycle, one that tantalizingly suggests a secret code: for the number of its songs—twenty-six—is of course also the number of letters in the Roman alphabet; and musicologists have undertaken various ingenious attempts to discern an alphanumeric key or cypher in their distribution. Does the third song, for instance, “Der Nussbaum” (The Walnut Tree), in which a young woman dreams of a bridegroom, have some particular significance to the addressee, herself presumably about to see her own dream fulfilled, and whose name—Clara—begins with the third letter of the alphabet?

Or perhaps it is rather the eleventh song, “Lied der Braut” (Song of the Bride), that refers to this particular bride, whose name would, by German-speakers, more typically be spelled with a K—which is the eleventh letter; followed then in her name by an L, the letter assigned numerically to the next song, also written for a bride. Does the thirteenth song, “Hochländers Abschied” (Highlander’s Farewell), refer to Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (1809-1847), the couple’s brilliant contemporary, both by way of its Scottish theme—Mendelssohn is celebrated both for his Hebrides overture and for his Scottish Symphony—and simply because the thirteenth letter of the alphabet is “M,” for Mendelssohn.

How disconcerting, then, for musicological sleuths that the only Myrthen text that refers explicitly to a letter of the alphabet should not occupy the corresponding place in the sequence! “Rätsel” (Riddle), the sixteenth song in the cycle, is Schumann’s setting of a text by Karl Kannegiesser, itself the German translation of a poem by Catherine Maria Fanshawe (1765-1834). Fanshawe’s “Riddle on the Letter H” is a coyly Byronesque meditation on a peculiar feature of the English class system, the shibboleth of the quite literally upwardly aspiring (think Liza Doolittle attempting to pronounce “Hertford, Hereford and Hampshire”):

‘Twas whispered in Heaven, ’twas muttered in hell,

And Echo caught faintly the sound as it fell;

On the confines of earth ’twas permitted to rest,

And in the depths of the ocean its presence confes’d;

‘Twill be found in the sphere when ’tis riven asunder,

Be seen in the lightning and heard in the thunder;

‘Twas allotted to man with his earliest breath,

Attends him at birth and awaits him at death,

Presides o’er his happiness, honor and health,

Is the prop of his house, and the end of his wealth.

In the heaps of the miser ’tis hoarded with care,

But is sure to be lost on his prodigal heir;

It begins every hope, every wish it must bound,

With the husbandman toils, and with monarchs is crowned;

Without it the soldier and seaman may roam,

But woe to the wretch who expels it from home!

In the whispers of conscience its voice will be found,

Nor e’er in the whirlwind of passion be drowned;

‘Twill soften the heart; but though deaf be the ear,

It will make him acutely and instantly hear.

Set in shade, let it rest like a delicate flower;

Ah! Breathe on it softly, it dies in an hour.

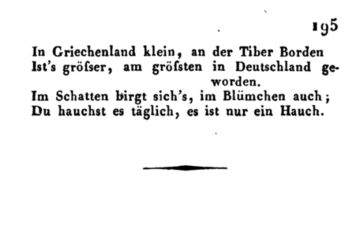

Fanshawe’s “Riddle” is equaled in cleverness by Kannegiesser’s German version, used by Schumann for the sixteenth—and not, alas, the eighth—of his Myrthen. For the German translator must naturally choose entirely different words and contexts to suggest the presence, often unheard, of the letter of the alphabet that is the solution to the riddle; nor can he rely on the densely socio-political meaning of the “aitch,” whose pronunciation (or rather, whose non-pronunciation) reveals the speaker’s class origins—for German society does not operate according to that particular code. Instead, he must resort to a feint of his own invention, the suggestion of the breezy letter “H” in his poem’s final word, which is, however, left unspoken, merely conjured up in the reader’s mind by the text’s penultimate rhyme. But more on this anon.

Recently I had the opportunity to hear Myrthen sung live, whole or in part, on two occasions. Both performances featured my friend Annina Haug, mezzosoprano and member, as I am, of Besuch der Lieder, a Switzerland-based group offering house concerts of classical art-song repertoire (and about which I have written here and here). The first occasion was, however, not one of our evenings, but a concert given at the home of Richi Irniger, an octogenarian doyen of the Zurich music scene who tirelessly stages semi-public events at his villa on the affluent Zürichberg. This latter-day Maecenas opens his doors regularly to sizeable crowds of classical music lovers, who are treated to performances by professional artists from near and far, as well as to a light buffet following the concert; the visitors’ contributions to a collection box at the exit go entirely to the musicians.

At Richi’s home, early last month, Annina sang the entire Myrthen, together with our baritone colleague Samuel Zünd. The singers split the cycle between them, with Annina taking on just over half the songs. She had elected to perform those based on texts in a clearly “female” voice, or written from a formulaically “feminine” perspective, including the two bride’s Lieder and “Der Nussbaum,” canonically associated with Clara. But there are also among the 26 Myrthen certain songs whose texts are epicene, easily assignable to neither conventional gender—non-binary, in today’s parlance; and among these is “Rätsel,” its English original by a woman, its German version by a man, and with no discernible sexual markers in the voice posing the eponymous riddle. And to which the answer, in German as in English, albeit with different nuances, is “the letter H,” left pathetically tacit in the original (“Set in shade, let it rest like a delicate flower; / Ah! Breathe on it softly, it dies in an hour”—emphasis supplied) but literally prompted, as if by a souffleuse, in the translation, whether for want of a similarly unaspirated clue, or because the Saxon spirit tends to less subtlety than the Anglo: “Im Schatten birgt’s sich, im Blümchen auch. / Du hauchst es täglich, es ist nur ein Hauch” —where Hauch means “breath” or “breeze”, or indeed, in one inflection, “aspiration”.

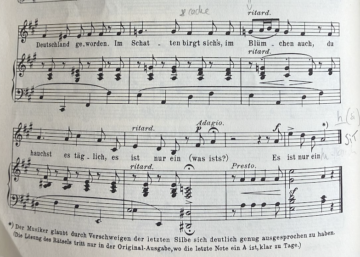

Schumann, however, evidently nonplussed by such a flatfooted giveaway, elects to suppress the solution in the poem’s ultimate substantive (although of course it is telegraphed in the verb that begins the last line: “Du hauchst es täglich” means “You breathe it daily”) and replaces it with an ellipsis, the device known in rhetoric as aposiopesis: trailing off into silence in order to suggest something that is, for whatever reason, unmentionable. Schumann’s adaptation of the last distich of Kannegiesser’s text runs thus: “Im Schatten birgt’s sich, im Blümchen auch. / Du hauchst es täglich, es ist nur ein (was ist’s?)” In other words, in Richard Stokes’s re-Englishing, “It’s concealed in the shade, and the tiny flower, / You breathe it daily, it’s merely a… (what is it?)” In the Urtext or original edition of the sheet music for Myrthen, Schumann leaves the choice of final enunciation up to the singer: or rather, he grants him (or her) permission to sing nothing at all. “Der Musiker glaubt durch Verschweigen der letzten Silbe sich deutlich genug ausgesprochen zu haben,” reads the footnote to the final note in the vocal score: “The musician is confident that, by muting the last syllable, he has expressed himself with sufficient clarity.” When Annina sang “Rätsel” at Richi Irniger’s, she was evidently not filled with such confidence, since the last sound she made was a very softly uttered—indeed, breathed—“Haaauuu….” It might have almost been the word Hauch, or “breath,” which is, incidentally, a near-homophone of her own family name, Haug.

Okay, I thought to myself, this is my friend’s manner of affixing a vocal seal to her work, of weaving her signature into the texture of her performance, the way an archaic Greek rhapsode might have frequently included his own name in his poetry, as proof of authorship. And well she might, I reasoned, in a professional musical world of increasing competition and challenge. More power to her!

It wasn’t until the second time I heard the song performed live, at the end of June, that I understood what was really going on. On June 30, Besuch der Lieder was invited to stage a concert—a Liederabend—at the home of Antonella Pilotto and Pietro De Marchi, an Italian-Swiss couple who were retiring from their work as teachers of Italian and leaving Zurich for Pietro’s ancestral home in Milan. The two bibliophiles, Pietro a published Italian-language poet, Antonella a published translator of Italian verse, requested a program of songs about books, poetry, and music… a fairly tall order in the case of the first of the themes, and all too obvious in the case of the second and third. After all, classical Lieder (ditto chansons, canzone, and art songs) are entirely composed of poetry and music: they are the very apotheosis of those two sublime forms. While as for books as such, which regularly contain poems and musical scores as their content, they are themselves only infrequently the actual object of lyrical reverie.

Nevertheless, in a series of conversations held mainly by group chat, we were able to put together a program that met the desiderata of our hosts, while also taking advantage of the repertoires of our chosen musicians (whose particular availability for a gig, both temporal and geographic, is often a decisive factor). The crew this time comprised, apart from me in my accustomed role as moderator, Annina herself; Jakob Pilgram, tenor; and the pianist, composer, and founder of Besuch der Lieder, Edward Rushton. We chose songs about writing (Schumann’s setting of “Belsatzar,” by Heinrich Heine, on the Babylonian sovereign’s hubristic inability to read divine messages), about books (Schumann with Heine again, whose “Mit Myrten und Rosen” imagines a volume of poetry as a coffin for unrequited love), and even one about lexica, a faiblesse of Antonella’s and Pietro’s (Edward Rushton’s setting of “Lisez bien les vieux dictionnaires,” by Guillaume Jean-Roi, from his 1996 song cycle). For my part, I requested “Rätsel,” from Myrthen, having been so taken by Annina’s recent performance, and reasoning that, if it did not actually feature a Buch as its poetic theme, yet it was all about a Buchstabe (letter of the alphabet), without which there would be no books.

My request was honored by my colleagues but, to my surprise, Annina and Jakob were firmly agreed that the latter would be singing it. When I asked why not Annina, the true secret of the song was revealed: Schumann had gone Kannegiesser—and Fanshawe, for that matter—one better and included a musical joke in his setting, perhaps the only one of its kind in the entire corpus and accessible exclusively to those trained in the German musical tradition. For that final note, accompanied by the singer’s muting of the final syllable of the text, is in fact, in the German system of key notation, what is known as an H—pronounced “Ha”—the equivalent of a b major in the English system. And thus the accompanist in fact plays the solution to the riddle, which thereby remains a secret to the unversed listener. So why then would Annina not sing it? Because the transposition of the score for her (mezzo) voice had transformed that note into an A—an a major—thus effectively stepping on the punchline. Jakob’s tenor, meanwhile, could easily accommodate the “secret” note. (This also explained why Annina, and not Samuel, had sung “Räthsel” at Richi’s, his voice being in that venue equally “out of range” for the musical resolution.)

What then might be the significance of this letter doubly hidden in the Myrthen, a name whose antiquated form bears a silent “h” within itself (as does the title of the poem, which could in Schumann’s age be written with the alternative spelling “Räthsel”)—doubly hidden because the letter is concealed within a riddle, and because the text of that riddle is not included in the “right” (i.e. eighth) position in the sequence? Could it be that Schumann’s coyly secreted “H” stands for the occasion that has given rise to the entire cycle, and which has had to struggle, like the heroic solver of the riddle him- or herself (or even: like the canonical riddle solver Oedipus, similarly oppressed by a tyrannical father); has had to struggle to find its way into the light of legitimacy and acceptance? Does it stand for the very Hochzeit (wedding) that was to be celebrated the day after the musical gift’s presentation? And does the song’s position as number sixteen in the sequence result from the doubled “H” in Hochzeit—two times eight, the letter’s position in the Roman alphabet?

At any rate, when he performed the song chez Antonella and Pietro, Jakob merely mouthed the note that Edward was producing on Pietro and Antonella’s Schimmel behind him, and left the coda’s decipherment up to our polyglot audience.

*

Four years after Robert and Clara’s wedding, in 1844, Edgar Allan Poe published “The Purloined Letter,” the third in a trilogy of stories featuring the brilliant detective Auguste Dupin, among the inspirations for Sherlock Holmes. In Poe’s narrative, a devious minister has stolen a letter—a handwritten communication—from a noblewoman and is preserving it as a prospective means of blackmailing her; the story concerns the futile search for the compromising document in all manner of recondite locations by the police force, followed by Dupin’s skilled divining of its whereabouts, and his retrieval of the letter from its virtually undisguised “hiding” place. In the mid-1960s, in one of his notorious seminars, Jacques Lacan made rather a meal of the tale, which he had read in Charles Baudelaire’s French translation. For the psychoanalyst, Poe’s story exemplifies the inevitability of repressed psychic material finding its way, albeit in distorted form, to the surface: the seminar ends with the celebrated assertion that “a letter always arrives at its destination.” What “The Purloined Letter” certainly does manifestly demonstrate is the expediency of concealment in plain sight. Dupin manages to think his way into the blackmailer’s mind, and to discover the sought-after object displayed carelessly in a prominent place in the minister’s quarters. He is able to do this, as he slyly indicates in my epigraph, because he shares with the devious minister a penchant for poetry—and thus for folly: in this case, the folly of supposing that his folly will be overlooked in the quest for evidence of his supposed deviousness.

Four years after Robert and Clara’s wedding, in 1844, Edgar Allan Poe published “The Purloined Letter,” the third in a trilogy of stories featuring the brilliant detective Auguste Dupin, among the inspirations for Sherlock Holmes. In Poe’s narrative, a devious minister has stolen a letter—a handwritten communication—from a noblewoman and is preserving it as a prospective means of blackmailing her; the story concerns the futile search for the compromising document in all manner of recondite locations by the police force, followed by Dupin’s skilled divining of its whereabouts, and his retrieval of the letter from its virtually undisguised “hiding” place. In the mid-1960s, in one of his notorious seminars, Jacques Lacan made rather a meal of the tale, which he had read in Charles Baudelaire’s French translation. For the psychoanalyst, Poe’s story exemplifies the inevitability of repressed psychic material finding its way, albeit in distorted form, to the surface: the seminar ends with the celebrated assertion that “a letter always arrives at its destination.” What “The Purloined Letter” certainly does manifestly demonstrate is the expediency of concealment in plain sight. Dupin manages to think his way into the blackmailer’s mind, and to discover the sought-after object displayed carelessly in a prominent place in the minister’s quarters. He is able to do this, as he slyly indicates in my epigraph, because he shares with the devious minister a penchant for poetry—and thus for folly: in this case, the folly of supposing that his folly will be overlooked in the quest for evidence of his supposed deviousness.

In “Räthsel,” Schumann plays the same trick as Fanshawe and Kannegiesser, both of whom hide the solution to their poetic riddle in plain sight; Schumann, for his part, poses a musical riddle, and hides his solution in plain hearing. Musicians, by this token, are even greater fools than poets.

Holy fools, that is.

*

Thanks to Annina Haug for invaluable advice and assistance. Any errors, musicological or otherwise, are my own.