by Bill Murray

In my exuberance after a spring trip to Kenya, Tanzania and Zambia, I proclaimed Africa the world’s greatest travel destination. It’s only fair to defend my thesis, for surely others will disagree.

First let’s dispense with the ‘Africa is not a country’ technicality by defining the travel to Africa that I have in mind as being, wherever the location, by some measure more raw, or relatively less mediated than a trip to most places in Europe or Asia.

What I have in mind for my ‘Africa’ is a place that affords a frontline opportunity for real experience of real life. Simple as that. In so much of Europe and much of Asia, what you’ve come to see and do is mediated by reservations, ticket punchers, tour guides, maîtres d’ and so on, putting the experiencer at some separation from the experience — the food in sought-after restaurants, the remnants of the Colosseum or Hadrian’s Wall or Stonehenge, cultural events like bullfights in Madrid, Japanese Sumo wrestling or the changing of various guards before various palaces from Beijing to Stockholm to the Kremlin. These are all surely there, but they are presented to you.

The simple elegance of Spanish tapas, the majesty of the Duomo, the magnificence of a Rodin in Paris, a van Gogh in Amsterdam or a David in Florence, come with a visitor’s expectations of a place because of its usually well-deserved reputation. The Bwindi Impenetrable Forest in southern Uganda comes with no such burned-in reputation, and it will utterly amaze you.

Most first time visitors to the African continent have no idea what they’re about to experience, which is the point, and the whole fun. Unlike travel to Europe, a reputation for historic human achievement isn’t what we’re after here. Maybe we’ll go see the ‘big five’ is about as far as travel agent mediation gets in shaping expectations of a safari.

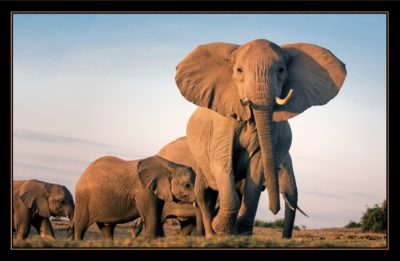

Comparing the grandeur of Versailles’ Hall of Mirrors, the delight of Thai cuisine or any other product of human endeavor with the experiences that make Africa the greatest travel destination is a category error. It’s not the same thing to equate, under the broad category of ‘travel destinations,’ the bas relief carvings at Angkor Wat to watching an elephant family bathing at the water hole.

If you are ever fortunate enough to go and see African wildlife, or to get personal enough with rural African people — whose experiences are very different from yours — to compare your life with theirs, it will open up a whole new way of seeing.

French tourism literature says there are some 140 musées in Paris alone, and some are showcases of the pinnacles of human achievement. If I designed the perfect day it might include a couple of hours at Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum. In contrast, in Africa, so much culture isn’t curated in museums. It’s there plain as day, living on the street, right in front of your eyes.

Living in Africa is so much more immediate. To say the least, the Okavango Delta and the two Luangwa National Parks and the Virunga National Park and Amboseli and Lake Malawi are places without the intervention of such constructs as “the 25 must-try restaurants in Milan.”

Where culture and history are in African museums, to pick one example, the National Museum of Ethiopia in Addis Ababa presents an unassuming edifice losing the race with decrepitude. It’s reminiscent of when public buildings were built differently – not sleek and for show, but stolid and tall-ceilinged and drafty (at least Addis’s museum would be drafty if it were in a cooler part of the world).

Inside is something astonishing. On display in a room that might contain a collection of arrowheads, or beetles and butterflies stuck through with pins in a medium-sized American city, stands “Lucy” or AL 288-1, “the fossilized skeletal remains of several hundred pieces of bone fossils representing 40% of the skeleton of a female” hominid who lived there 3.18 million years ago.

•••••

African experiences, done well, bring you up closer, more face to face, with the tenuousness, the plaintiveness of the human experience. In just about all of Africa any pretentious facade has been chipped away.

On Gorée Island near Dakar, the slaving past is right there for you to see, not roped off at the far end of an endless queue, but joined by and overlaid with the living of real life, the imperative of real Senegalese local people trying to make a living.

In African tourism, life is right there in front of you, showing you which plains animal has gone to meet its maker overnight on the savannah. Or spying a Martial Eagle standing astride one of its formidable eggs, glaring in cold defiance, utterly daring you to come one inch closer. Or in the intricate organization of a clan of two dozen hyenas at their den. Or perhaps on a remarkable afternoon, the mating of leopards.

African tourism is also the chance to ponder the frailty of human political systems while sitting stock still in traffic in Dar es Salaam — one of the places whose experiment with ‘Socialism’ under Julius Nyerere thirty plus years ago, however well meant, seems to have kept it perennially stuck at a disadvantage and forever straining to catch up.

There are few middle market accommodations in far-flung national parks and prime wildlife locations; that makes wildlife viewing trickier. It’s a fair criticism. At first glance, it looks like there are either heavenly thousand dollar per person per night safari lodges usually brokered through European or American tour companies and marketed abroad, or there are hovels.

Some of our utterly best-in-the-world travel memories come from Africa, and a large part of that is African style and grace, what you might call presentation-panache. Compare and contrast the challenges presented in serving you a memorable dining experience at the Adlon on the Unter den Linden with pulling that off where every last thing comes bouncing down a dusty road once a week in a panel truck.

(Granted, if you’re at the far end of a sweaty ninety minute small plane ride yourself, or you just spent six hours bouncing in a Landcruiser to get here, you just may be more disposed to be favorably impressed by a nice presentation here than by the jaded garçon at Les Deux Magots.)

Still and to be fair, it’s not all butterflies and puppy dogs out there. I have an indelible memory of a story told by our intrepid, Africa-professional friends, a couple who lived in and camped across Africa for so long it became a matter of course, and who still yet managed to turn up somewhere on the far side of Fort Portal in Uganda so rank that they pitched a tent inside their own hotel room.

Practically speaking, if you hunt for them you can sometimes find, there middle-level hotels and lodges. At the Ol Tukai Lodge, not far from the airstrip in the Amboseli National Park, we once we had a front porch that opened onto a view of nothing but savannah and families of elephants, for somewhere in the three or four hundred dollar a night range. Ordinary American hotel chains have done a whole lot of catching up to prices like that since Covid. The Serena chain has midrange lodges from Kenya to Congo to Mozambique (and incidentally, a hotel in Kabul, if you’re game.)

•••••

If you’re ever able to enjoy a safari experience, by all means, please, please do it. The whole experience, well-crafted and refined by constant hospitality for a century and a half by now, is presented with every intention to awe. And it has for me, time after time.

Lions calling out in the predawn while everybody gathers around the pot of coffee, drowsy anticipation around the long-burning embers of last night’s ironwood fire, then the lumbering morning sun — if your driver/guide is good, artfully positioned behind a herd of grazing … anything, really, makes for as great a start to the day as any you could dream up.

The safari campfire at night can bring African life right up close before your eyes. Once in the Zambian bush, our guide Aubrey grew melancholy by the campfire. The lantern cast an unsure light and a rich Milky Way splayed out overhead.

Aubrey once had three sisters and three brothers. Now he’s the head of the family. He has one sister, and more matter-of-factly than I think I would, he told us the others died of “natural causes.”

His mother’s brother was ill south of Lusaka. She went to care for him. While she was gone, one of her sons, younger than Aubrey, took ill. They sent word and she boarded a bus home. A few kilometers south of Chipata, the nearest proper town, the bus blew a tire and his mother was killed. Aubrey’s father was already ill, so Aubrey went to get the body and they buried her the next day. His father lost the will to live, Aubrey says, and died four months later.

“This is African life,” he said.

Aubrey looked tired. This was all heartbreak and woe.

He told another story, though, and brightened as he did. It was hard to understand it all, but the outline is that, according to a Zambian folk practice, a log is set alight to burn for one month, and during that month a couple must conceive.

The prospective groom’s uncle on his mother’s side goes to his desired bride’s family to negotiate a bride price – cows, for example, or maybe even simply that they can visit their daughter as often as they want. Once the bride price is settled, an elaborate ritual takes place to get her to the wedding bed.

The groom-to-be arrives alone at the young girl’s village and the mother of the bride leads him to their house. It starts with the young man inside alone. The young girl’s mother brings her to the house. She won’t come in. There is cajoling. Now the door is open. He throws coins; She steps closer.

In the end they spend the night and don’t come out until the next day, and the next day they are married. It’s a festive day, with food offerings from both sides of family, and the dowry is delivered. The catch is, if the bride isn’t pregnant by the time that log goes out, in a month, the bride’s family can give the boy back.

“I am fighting that log,” he smiled. Aubrey was newly wed.

•••••

In the end, where you travel depends on what you’re after, and if you’re after the five best small hotels in Tuscany, Tuscany will deliver. But if you’re after a life changing opportunity to ground yourself on planet earth with your fellow humans and other living beings alike, to share in the fleeting drama of life on an increasingly distressed planet, to live and to learn and to get to some of the real soul of the planet, there is only one choice. Visit Africa.

•••••

I write things like this three times a week at Common Sense and Whiskey. Please join me.

•••••