by Derek Neal

There is a scene near the end of First Reformed, the 2017 film directed by Paul Schrader, where the pastor of a successful megachurch says to the pastor of a small, sparsely attended church:

There is a scene near the end of First Reformed, the 2017 film directed by Paul Schrader, where the pastor of a successful megachurch says to the pastor of a small, sparsely attended church:

You’re always in the Garden. Jesus wasn’t always in the Garden, on his knees, sweating drops of blood. No, he was on the Mount, in the temple, in the marketplace. But you’re always in the Garden. For you every hour is the darkest hour.

The small-town pastor, played by Ethan Hawke, is in a state of constant suffering and isolation. His son, who he pushed to enlist in the army, has been killed in combat; his wife has left him; his home contains no furniture or decoration; he drinks heavily and writes in a journal; he rejects all those who try to help him; he is dying from cancer. Despite all this, he is a good pastor and cares deeply about the people he serves.

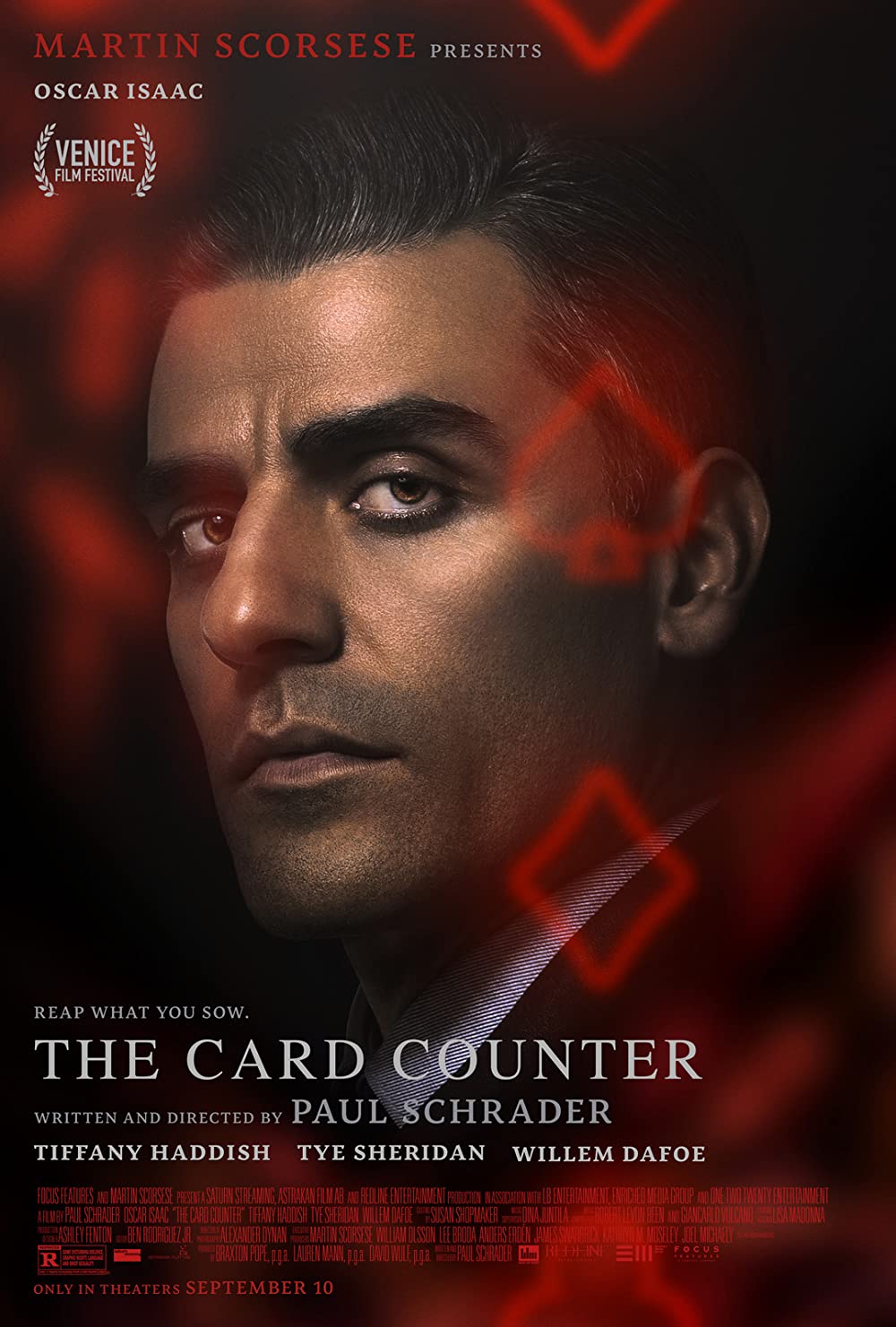

In another recent Paul Schrader film, The Card Counter (2021), the titular character played by Oscar Isaac is another man who is “always in the Garden.” He, too, drinks heavily and keeps a journal; he drives from city to city by himself, playing blackjack at various casinos before moving on to avoid attracting unwanted attention; he stays in budget motels and covers the furniture with sheets; he has no friends and no fixed home.

It may not be readily apparent from these descriptions, but the characters played by Hawke and Isaac are sympathetic ones. We see that they suffer due to events beyond their control—Ernst Toller (Hawke), because of the loss of his family, and later, as a result of the environmental destruction caused by big business and its integration with the church of which he is part; William Tell (Isaac), because of his past at Abu Ghraib, a past in which he was forced to torture others against his will, although he insists on taking responsibility for his actions. These events have led both men to accept a life of quiet pain as their fate. This is what they know, and it is, in a way, comfortable for them.

But one cannot live in the Garden forever. Even Jesus did not stay in the Garden of Gethsemane, as Toller is reminded. Or, as Woody Harrelson tells Matthew McConaughey in True Detective, “Not everybody wants to sit alone in an empty room beating off to murder manuals. Some folks enjoy community. A common good.” But how does one leave the Garden and rejoin the world—community—when the world is a strange and frightful place, a place where prosperity is only possible through destruction, as in First Reformed, a place where the walls of cells are smeared with shit and blood and bodily fluids, where people are pawns ground to dust in a global game, as in The Card Counter? How does one avoid being betrayed, as Jesus was upon exiting the Garden of Gethsemane? Schrader’s films present a possible answer to this question.

The films are shot in a simple style. The camera does not move often; outside of extensive voiceover, there is minimal use of a soundtrack or other sound that would not be produced from the images we see; there are few special effects. Often, a shot will be established with no characters present. Someone will walk into the scene, then out of the scene, and perhaps back into the scene again. Time slows down in these films; they are the antithesis of Hollywood filmmaking, with its quick cuts and constant action. Schrader refers to this style as “transcendental” and has written that it “expresses a spiritual state.” This is true. The most moving moments in the films are when Schrader allows his characters to leave the Garden, and we, the viewers, leave it as well. In these moments, Schrader has focused our attention so acutely that we bring a new awareness to everyday activities. When Toller and another character ride bikes in First Reformed, we feel like we are riding, too. Toller says in voiceover:

Mary and I rode the rail line trail. I had not ridden a bicycle I think in twenty years. I was afraid I would fall. It is amazing the simple curative power of exercise. It’s God given.

We realize the profound nature of this simple truth. Yes, we think, riding a bike is special, and good. There is something transcendental about it.

In The Card Counter, a similar moment happens when Tell (Isaac’s character) and another character walk through an illuminated light exhibit at night. The exhibit, in truth, is tacky, but Tell is there with a person he cares about, and they become like children, awed by the LED lights and happy to be in the presence of someone they might love. In both films, these moments of “transcendence” occur when the main character is with a possible love interest, and love is the redeeming power that will deliver one from suffering. But it is up to each character to accept this love or reject it.

Let’s return to First Reformed. Toller is pursued by a woman named Esther from the megachurch. She attends his services; they spoon soup together for the less privileged; it seems that they slept together once. Toller, however, is not interested in the care that Esther offers him, perhaps because she seems more like a concerned mother than a romantic partner. There is no passion in their interactions. Esther is someone who would “be good for him” because Toller is the typical man who is incapable of taking care of himself—at one point, he begins mixing Pepto-Bismol directly in the glass with his whiskey.

The breaking point for Toller is when Ester calls the hospital without his knowledge and discovers that he’s been registered for a gastroscopy. Upon learning of this, Toller’s suffering turns to rage, and he berates her, violence simmering underneath the surface of his words:

I know what you want. I cannot bear your concern, your constant hovering. Your neediness. It’s a constant reminder of my failings and inadequacies. You want something that never was and never will be…I despise you. I despise what you bring out in me. Your concerns are petty. You are a stumbling block.

But a stumbling block to what? Where is Toller going? Perhaps to his misguided idea of salvation, which he thinks can only be obtained through self-denial and suffering. In truth, his forgiveness and salvation are right in front of him, if only he could see it.

In The Card Counter, Tell decides to take the chance that Toller is unwilling to. While travelling from casino to casino, he happens upon a security conference taking place inside one of them. His former commander in the army, a man who has never paid for the crime of directing the torture at Abu Ghraib, a man who, in fact, has benefitted from this by parlaying it into a career in the private sector, is giving a presentation on technological advances in security. Tell is recognized by another man at the conference, a character named Cirk, or “The Kid,” whose father was in the army with Tell. The father killed himself, unable to bear the pain of what he had done in Iraq, and Cirk wants to take revenge on the army commander, played by Willem Dafoe. Tell senses the possibility to atone for his past sins and invites Cirk to travel with him, thinking he can deter Cirk from his course of action and act as the father Cirk has lost. Tell chooses to reenter the community of humanity in an attempt to do good, so that another might succeed where he has failed. He also agrees to partner with a woman named La Linda, who connects gamblers to financiers. There is attraction between the two, but Tell resists. At a non-descript motel by the outdoor swimming pool, Tell explains to Cirk:

In The Card Counter, Tell decides to take the chance that Toller is unwilling to. While travelling from casino to casino, he happens upon a security conference taking place inside one of them. His former commander in the army, a man who has never paid for the crime of directing the torture at Abu Ghraib, a man who, in fact, has benefitted from this by parlaying it into a career in the private sector, is giving a presentation on technological advances in security. Tell is recognized by another man at the conference, a character named Cirk, or “The Kid,” whose father was in the army with Tell. The father killed himself, unable to bear the pain of what he had done in Iraq, and Cirk wants to take revenge on the army commander, played by Willem Dafoe. Tell senses the possibility to atone for his past sins and invites Cirk to travel with him, thinking he can deter Cirk from his course of action and act as the father Cirk has lost. Tell chooses to reenter the community of humanity in an attempt to do good, so that another might succeed where he has failed. He also agrees to partner with a woman named La Linda, who connects gamblers to financiers. There is attraction between the two, but Tell resists. At a non-descript motel by the outdoor swimming pool, Tell explains to Cirk:

When I was in the service I was a bit of a lady’s man. Thought I was. But then the other stuff happened. The narrative was broken.

Tell eventually does pursue La Linda. He also gives Cirk $150,000 to see his estranged mother, go to college, and forget his ideas of revenge. Things seem to be turning around for Tell. He has left the Garden, but will he be betrayed?

After rejecting Esther, Toller in First Reformed has a second chance at redemption in the form of Mary, another woman who frequently attends his services. He counsels Mary’s husband, an environmental activist, whose despair for the future causes him to lose any sense of meaning in life—another man in the Garden. For their second session, Michael changes the location of their meeting to a trail in the woods. Toller arrives, finds Michael’s parked car, and begins walking down the trail. It’s winter in New York. The trees are bare; the ground is covered in days old snow mixed with dirt. Toller finds Michael’s body, its face blown off by a shotgun blast, the dirty snow covered in fresh red blood.

In the weeks following, Toller helps Mary pack up Michael’s belongings, goes on the bike ride with her, and comforts her when she visits him in the middle of the night after having a panic attack. Something seems to be happening between them, but Toller is a pastor, and Mary is a pregnant widow. Mary goes to live with her sister; Toller begins following the same path as Mary’s husband after he finds his laptop, alerting him to the fact that his church and his job are funded by one of the highest polluting companies in the country. Toller finds Michael’s suicide vest, too.

The endings of both films offer contrasting visions of what may happen when one leaves the Garden. Toller is preparing to blow himself up, along with everyone in attendance at the service celebrating the 250th anniversary of his church. At the last moment, Mary enters the church, and he cannot go through with his plan. Instead, he thinks, he will kill only himself. He wraps his body in barbed wire and lifts a cup of drain cleaner to his mouth. This scene is excruciating; Toller’s desire to suffer knows no bounds. Then Mary appears, the cup passes from him, and he and Mary embrace. The film ends. Toller leaves the Garden and has a second opportunity to raise a child, to have a family, to have a life.

The Card Counter presents a darker vision. Tell is at the final table of a World Series of Poker event when he receives a text message from Cirk, who is supposedly on the way to see his estranged mother. The text, however, shows a picture of the former army commander’s house. Tell has been betrayed; Cirk has not given up his plan for revenge but has used Tell’s money to facilitate it. Tell leaves the tournament to follow Cirk, but he’s too late—of course he’s too late—and what he does next puts him back in military prison. The last scene of the film ends in a similar way to First Reformed: La Linda arrives at the prison, yet unlike Toller and Mary, she and Tell cannot embrace. She puts a finger to glass, so does Tell. Their hands cannot touch.

Schrader has a new film that I haven’t seen yet. It is called Master Gardener. The poster features a striking man in semi-profile, just like First Reformed and The Card Counter. A summary of the film says that this man keeps a journal, and we can reasonably assume that he drinks heavily, narrates his journal entries in voiceover, and suffers deeply. This film, along with Schrader’s two recent films, may form a later period transcendental trilogy for Schrader. At some point in the film, the main character will leave the Garden. What will happen next?

Schrader has a new film that I haven’t seen yet. It is called Master Gardener. The poster features a striking man in semi-profile, just like First Reformed and The Card Counter. A summary of the film says that this man keeps a journal, and we can reasonably assume that he drinks heavily, narrates his journal entries in voiceover, and suffers deeply. This film, along with Schrader’s two recent films, may form a later period transcendental trilogy for Schrader. At some point in the film, the main character will leave the Garden. What will happen next?