by Steven Gimbel and Gwydion Suilebhan

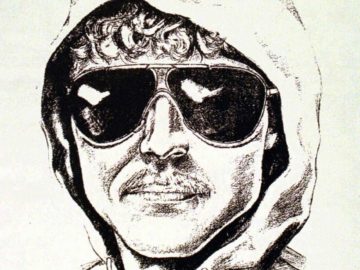

From the late 1960s to the mid 1980s, America was beset by a haunting array of serial killers: the Zodiac Killer, the Son of Sam, John Wayne Gacy, Ted Bundy, and the Unabomber, Ted Kaczynski, who just recently died in prison. For two dark decades, serial killers stalked the country, eroding our collective sense of safety and casting disturbed shadows over a world that made less and less sense every day.

In the 1990s, serial killers started to give way to mass shooters, who have terrorized Americans with increasing frequency for the past 30 years. Today, instead of protracted investigations that take years to find their targets (and in some cases never do), we have rotating 24-hour news cycles full of AR 15-wielding villains. Killers who used to operate for years, murdering victims in methodical patterns, have been replaced by death-cultists who kill the same number of people (or more) in one bloody event.

Serial killers defy easy understanding. In their horrific acts, they embody human immorality and insanity, but by eluding the authorities for months or even years, they demonstrate patience and discipline. They seem to be both malevolent and (in some ways) civilized.

Somewhere deep inside, we all want to believe that serial killers are impossible. Anyone smart enough to evade capture, write a manifesto, or plan elaborate rituals shouldn’t also be able to commit gruesome, inhuman acts. They remind us that our understanding of humanity is incomplete (at best) and perhaps quite flawed.

In the 21st century, we almost have a nostalgia for serial killers. Netflix and other media companies have capitalized on it many times over. In 2018, the release of Unabomber: In His Own Words followed the 2017 television miniseries Manhunt: Unabomber, and countless others have focused on several of the names we listed above. The portrayal of serial killers, compared to the behavior of more recent mass shooters who threaten our schools, theaters, businesses, nightclubs, and houses of worship, makes them seem almost admirable for their meticulously-indulged obsessions and their over-wrought brilliance.

Immanuel Kant believed that being virtuous could, in some ways, make an evil person even more evil, and serial killers prove his point. A brilliant, brave, and patient murderer is more of a threat, in theory, than a killer full of temporary, unfocused rage… unless that killer has an automatic weapon.

The automatic rifle has had the effect of democratizing mass murder. George Santos, Ana Paulina Luna, and Andrew Clyde have proudly worn lapel pins celebrating the AR-15, and Lauren Boebert and Barry Moore, among others, sponsored H.R. 1095, a resolution “To declare an AR-15 style rifle chambered in a .223 Remington round or a 5.56x45mm NATO round to be the National Gun of the United States.” It’s almost as if their goal is to make sure that anyone with a half-baked cause can become Ted Kaczynski without having to hide out in a remote cabin for decades.

Our present-day mass murderers have a very different profile than yesterday’s serial killers. Instead of a secretive, seething antipathy, they seem to be possessed by loud, public depravity. School shootings in schools like Columbine, Sandy Hook, Parkland, and Uvalde speak volumes, as do workplace rampages like those at the Santa Clara rail yard, the Federal Express facility in Indiana, and the Walmart in Chesapeake, Virginia. Loudest of all, perhaps, are the shootings born of bigotry, like the massacres at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, and the Tops Friendly Market in Buffalo. These are killings that require no brains, just bullets. The killers never escape. They don’t outsmart anyone.

Serial killers may have undermined our shared sanity and sense of safety, but mass shootings shake our confidence in America’s underlying social structure to its core. Unrelenting violence at a scale once unthinkable outside of war feels like an effort to renegotiate the social contract and destroy the democratic institutions that guarantee fairness and inclusion. Many mass shooters, after all, have been influenced by one or more on-air or online talking heads pushing updated versions of Nazi Great Replacement Theory and a range of conspiracies dehumanizing anyone seeking fair treatment under the law.

Those talking heads may be the major social change most responsible for taking America from the Unabomber to Uvalde. Where Ted Kaczynski had both the brain and the hands of a killer, as both the author of the manifesto and the builder of the bombs, 21st century technology, from cable news to the internet, has allowed for the separation of mind and body. Hateful pundits transmit bigotry into the ether, then claim innocence on the grounds that they haven’t actually hurt anyone themselves.

Meanwhile, an unpredictable few of their audience members, emotionally charged by their rancorous speech, await targeting orders, filled with a manufactured need to “defend Western values”, “make America great again,” and “restore the culture to its rightful owners.”

This dangerous phenomenon is called stochastic terrorism. It works just like the candy racks in grocery checkout lines. Stores know that a certain percentage of people will always make an impulse purchase, even if they don’t know precisely who will succumb to temptation.

In the same way, purveyors of hate on the web and on television do not know which viewers will snap, but they do know that a small percentage will. Like Kaczynski, they plot the undermining of the social order through violence, but unlike the Unabomber, they don’t do the deed themselves. They write the manifesto, but rely on their audience members to serve as weapon masters. They trigger their viewers, but keep their hands off of any actual triggers.

Ted Kaczinsky’s infamous manifesto railed against modern technology. His extensive mail bombing campaign targeted people who (in his mind) advanced industrialization, threatening the environment and degrading humanity. He was arrested in April 1996, just as the internet was dawning over America, half a generation or so before social media started to infiltrate our lives. Would he have railed against those technologies, too?

The irony is that those technologies have been used to help create Ted Kaczynski 2.0, the next generation of mass murderers. Our phones have become smart phones, and our televisions have become smart televisions, but our mass murderers no longer have to be smart at all. The death of the Unabomber offers us a moment to consider that in the decades since he was put behind bars, we’ve done nothing to stop mass killings. Indeed, if anything, we allowed them to morph into a new form.