by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

1.

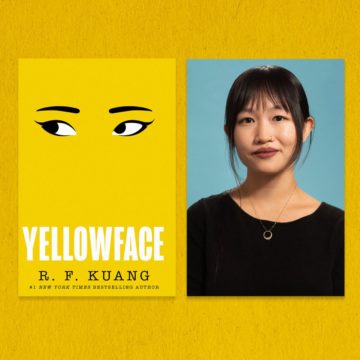

Does the title of the novel make you cringe or what?

In RF Kuang’s latest novel Yellowface, the setup is simple: within pages of the book’s opening, two frenemies –who met at an elite university–are having dinner together. Athena, who is Asian-American, has seen tremendous success in her work. The other woman June is white and has been anything but successful. Not surprisingly, June is envious of Athena’s career….Could it be because Athena is a drop-dead gorgeous person of color? Could it be because of her sexy British accent and tall ballerina-like figure?

Or maybe it’s because she is an incredible writer and knows what she’s doing?

June can only keep wondering…. Until, suddenly during Athena chokes on a pandan pancake and dies.

And yes, you guessed it: June steals Athena’s manuscript-in-progress…

2.

I am a big fan of RF Kuang, an author who refuses to publish in the same genre twice! I recently picked up her latest novel Yellowface, and was delighted when Roxane Gay announced it would be her bookclub pick for June. (I am also a huge fan of Roxane Gay!) (*)

There were many points before the plagiarized novel was published that June could have course-corrected. Why do you think she didn’t? What do you think was her point of no return? Why do you think the publishers were so quick to dismiss Candice’s concerns, and her suggestion of a sensitivity reader? What did you think of Kuang’s depiction of publishing and its inner workings? And how did you feel about the way Kuang wrote about the challenges, small and great, that writers of color sometimes face? Was she accurate? Too cynical? Not cynical enough?

When I started Yellowface, I was thinking along the lines of the ballet story, white swan/black swan… and the inevitable jealousy that is part and parcel of the art world.

This is even more intense in publishing with the intense monopolization of the industry, which basically has literary artists pitted against each other to claw their way to the top. Well, that is one version of it: a fierce but basically fair playing field. Another version is something like how June sees it. That there is a randomness to the process whereby publishing houses will choose their “it” artist and put a huge chunk of their marketing budget into launching that artist’s career. June feels the process is fundamentally unfair.

And yet, after stealing Athena’s manuscript June discovers Athena really can write—and spectacularly. June has no artistic vision whatsoever. What she does have is editing skills. And she is also not bad at plagiarizing—she is quite good at that!

June takes Athena’s draft (and it is still a draft) about Chinese labor during World War 1 and she rewrites it.

Or better to say she ghost writes it.

And it becomes a huge success.

Reading Yellowface, I was struck by the inviolability of artistic vision. Like in science, art is collaborative and entire teams are involved in bringing a work to life—and yet, it is the artistic vision that is the heart of the artistic endeavor. It was Athena’s vision and June outright steals it.

June keeps telling us that she totally re-wrote what was a terrible draft and it is now “hers”— Translators know how much close reading goes into creating a literary translation—and how a story in one language is translated, interpreted and transfigured into a work in a new language…. and yet, the story itself is still the artist’s, right? The translator is, in effect, writing a book. The translation is theirs, of course, but the book will always be that of the author’s.

And that is where June became delusional. Readers in the bookclub (myself included) felt that a huge part of her delusion is concerning her white entitlement attitude– since as readers, we are in June’s head the entire time as she makes excuse after excuse of why she “deserves” her new found success… thank you very much, Athena!

3.

Yellowface is generating a huge amount of buzz–partly because it is a fascinating takedown of US publishing and the way artists are packaged. Athena is not only “allowed” to write about Chinese history –but it turns out she is constrained to ONLY write about Chinese history. This is rich since she is unable to speak or read Mandarin and she herself talks of being pigeonholed into “immigrant story author.” This evokes the issue that the call for diverse voices is not being accompanied with diversity in the actual industry—for where is the call for it in publishing executives, literary tastemakers and agents?

In the world of RF Kuang’s novel, that means Athena is being branded as a writer of immigrant stories and there is a real push for her work to be “propulsive” and “televisual”—there must be conflict and stakes and worse, when June comes on board, the executives decide to brand June as “Asian” despite the fact that she is thoroughly of Irish descent. So, they encourage her to start writing under a new name June Song (Song is her middle name and sounds vaguely Chinese, they reason)… and in a surreal moment, she uses a photograph of herself in which her tan makes her look more Asian (I am not making this up) as the author picture. This is where the novel’s title comes from… if you want to know more about two much-discussed cases where white author’s published under fake Asian identities, please read this very critical review of Kuang’s novel in the Cleveland Review of Books.

June is awful. But what if the industry itself?

4.

It is not only artists that are being branded but the writing itself is being “managed”—many times with TV in mind. There is a certain style that is strongly promoted in workshops of short, almost journalistic sentences, snappy paragraphs, simple verb tenses, and no adverbs ever! Writers are taught to discard a lot of the language we speak and think in. Why is that?

In a fantastic essay last week in the LA Review of Books, Thalia Vacha wrote about Thomas Bernhard and his “extremely long paragraphs.” Reading Bernhard, who breaks many of the iron-clad rules enforcedin MFA programs, Vacha writes:

For my part, Bernhard kept me sane as I completed an MFA. Every time the idiosyncrasies in my work were critiqued in the name of craft (so-called), I would, as a matter of ritual, read a few pages of Bernhard—any would do—and would think how his work might be critiqued, perhaps even condescended to, in a workshop. The long sentences, the absence of plot, the rage, the propensity to tell (over and over again) rather than show—all stand opposed to the conventions of form and style that mark the MFA-to-industry literary pipeline.

The MFA-to-industry pipeline is interesting to consider, since in most countries there is not such a thing as an MFA program. In general, writers study anything in university and come to writing from various backgrounds. The study of craft is often self-study, alone in a room reading and trying to internalize one’s favorite novels. Last year, I wrote about my own experiences in American writing workshops in an essay in the Millions: Culture Shock: Reassessing the Workshop. At the time, I was more concerned with the way that storytelling styles that are representative of nonwhite cultures or subcultures are not easily placed or published.

5.

I finally got around to reading Mieko Kawakami’s best seller from a few years back, Breasts and Eggs, which is in part about the author’s real-life path to becoming a writer.

I think Japanese publishing is quite different from the US. First, historically, so many books have been published in serialized form. In newspapers or magazines. Kawakami’s real-life case mirrors that of her protagonist, by her starting off as a blogger. Her first novel was basically published online on her blog. Publishing in serialized form is quite a different kettle of fish since a writer doesn’t go back and rewrite after finishing the entire story. And each part must also be a stand-alone on some level. There must be something that each section ends with that keeps readers coming back.

I think publishing a novel on the Internet is exciting and I don’t know why it is not more popular in the English-speaking world. I can only think of the movie Julie and Julia that started off life as an online memoir. Kind of like Kawakami’s first novel, she put the book online slowly as she was writing it in real time and this was later picked up as the blog gained popularity.

(I had no idea that the author of the memoir Julie and Julia died during Covid of cardiac arrest. She was only 49).

Kawakami’s real break —and this is mirrored in the novel— came when a story she wrote won a prize in a writing contest. And that was that. In Japan, writers do not get MFAs. And there are no big conferences with agents presents where aspiring writers have to try to sell their work to an agent, who will then sell it to the publishers. Prizes are a big way in.

An author friend in Holland says the situation there is much like in Japan. Literary agents are not common and MFA programs do not exist. It is not financialized to the same level. And I do think with the exception of the UK which is taking on a more US model, most countries are more like Japan or Holland–but I am very curious to hear what others say.

6.

Speaking personally, up till now, in addition to many online writing workshops (but never as part of an MFA program), I have experienced two in -person writer’s workshops. The more recent one was the Lighthouse Conference in Denver, where I was in a workshop with a favorite novelist of mine, Katie Kitamura. It was fantastic! It was everything I had always dreamt a workshop could be, not only being with an artistically supportive cohort who genuinely loved reading books, but I came home and basically ripped apart my manuscript-in-progress. I was so happy and am now actually seeing real promise in the idea of workshopping. The conference part was so much fun! And the nightly readings of published authors like Katie Kitamura, Rachel Kushner, Rebecca Makkai, Claire Messud, and Amitava Kumar was thrilling!

This was a great experience especially since my first in-person workshop attempt in Kauai was stressful with a strong focus on selling, pitching, branding, networking.

This summer, I am trying again and will be studying at Sewanee, where I am excited to workshop with Vanessa Hua– and then at Bread Loaf, where I received a contributor’s award and I get to study with another favorite writer, Jess Row.

If anything interesting happens I will write about it in these pages when I get back…. But no matter what, I want to take Mieko Kawakami’s words from Breasts and Eggs to heart and just keep my focus on the writing itself—and the sheer joy of reading fiction! And not get caught up in hoop jumping and “publishing.” She says it better:

Writing makes me happy. But it goes beyond that. Writing is my life’s work. I am absolutely positive that this is what I’m here to do. Even if it turns out that I don’t have the ability, and no one out there wants to read a single word of it, there’s nothing I can do about this feeling. I can’t make it go away. I recognize that luck, effort, and ability are often indistinguishable. And I know that, in the end, I’m just another human being, who’s born only to die. I know that“in reality, it makes no difference whether I write novels, and it makes no difference if anyone cares. With all the countless books already out there, the world won’t notice if I fail to publish even one book with my name on it. That’s no tragedy. I know that. I get that.

Notes:

- Roxane Gay: One of the reasons I love Roxane Gay so much is she pours her energy into improving the world of publishing—actively supporting emerging writers (This includes financially). She is a treasure. I love her book clubs too. In January of this year, there was an especially vibrant club discussion about Age of Vice, by Deepti Kapoor. Right now, we are reading, Rivermouth: A Chronicle of Language, Faith, and Migration, by Alejandra Oliva, which I highly recommend!

- US PUBLISHING: There are many references and links in my essay in the Millions: Culture Shock: Reassessing the Workshop. Henry Lien wrote a similar essay for the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Association “Diversity Plus: Diverse Story Forms and Themes, Not Just Diverse Faces“

- Also: Guardian Interview: Rebecca F Kuang: ‘Who has the right to tell a story? It’s the wrong question to ask

- For more about Kuang’s earlier book Babel—her best so far in my opinion—See Claire Chamber’s essay on Babel at 3 Quarks Daily Translation as Colonialism’s Engine Fuel and Chicago Review of Books review by Daniel Rabuzzi: Translation as Oppression and Liberation and my short Substack post: Traduttore, Traditore: RF Kuang’s Babel: Or the Necessity of Violence: An Arcane History of the Oxford Translators’ Revolution

- I have not read this book yet but want to: The Death of the Artist: How Creators Are Struggling to Survive in the Age of Billionaires and Big Tech, by William Deresiewicz. There is also this book coming out in the fall (I have already preordered it): Big Fiction: How Conglomeration Changed the Publishing Industry and American Literature (Literature Now) by Dan Sinykin