by Rafaël Newman

Every human generation has its own illusions with regard to civilization; some believe that they are taking part in its upsurge, others that they are witnesses of its extinction. In fact, it always both flames up and smoulders and is extinguished, according to the place and the angle of view. —Ivo Andrić (tr. Lovett F. Edwards)

I was accompanied through the last week of October by a succession of Bosnians: Adnan introduced me to Sarajevo; Emir and Senad took me through Eastern Bosnia; Ajla and Merima led me down the valley of the Neretva River to visit the dervish monastery at Blagaj and the reconstructed bridge at Mostar; and Ahmo, the stoical busman employed by Funky Tours, drove me three 12-hour days in a row through the multiethnic heartland of former Yugoslavia.

It was the time of year when I usually accompany my partner, Caroline Wiedmer, a professor of Comparative Literary and Cultural Studies at Franklin University Switzerland, and a group of students on Academic Travel, the extramural component of a semester-long course with an international theme. (I have written about past travels here, here, and here.) “CLCS 220: Inventing the Past,” a course in memory studies Caroline has offered many times since 2007, has typically focused on French, German, and Polish sites of Holocaust remembrance, an early specialty of hers; this year it was devoted to Sarajevo, as well as to other towns in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and to a study of the culture of memory there, nearly thirty years after the Dayton Agreement put an end to the violence and atrocities surrounding the independence of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Our daughter, Hella Wiedmer-Newman, was also along on the trip. Her work as a doctoral student in art history at the University of Basel focuses on art and memorialization in postwar ex-Yugoslavia, and this, together with her growing proficiency in the Bosnian language, made her an obvious choice to lead some of the on-site seminars in Sarajevo. Read more »

Daniel Goleman’s

Daniel Goleman’s

The man who’d spoken to me before appears at my side and whispers into my ears again.

The man who’d spoken to me before appears at my side and whispers into my ears again. In the past decade, the writer Simone Weil has grown in popularity and continues to provoke conversation some 80 years after her death. She was a writer mainly preoccupied with what she called “the needs of the soul.” One of these needs, almost prophetic in its relevance today, is the capacity for attention toward the world which she likened to prayer. Another is the need to be rooted in a community and place, discussed at length in her last book On the Need for Roots written in 1943.

In the past decade, the writer Simone Weil has grown in popularity and continues to provoke conversation some 80 years after her death. She was a writer mainly preoccupied with what she called “the needs of the soul.” One of these needs, almost prophetic in its relevance today, is the capacity for attention toward the world which she likened to prayer. Another is the need to be rooted in a community and place, discussed at length in her last book On the Need for Roots written in 1943.

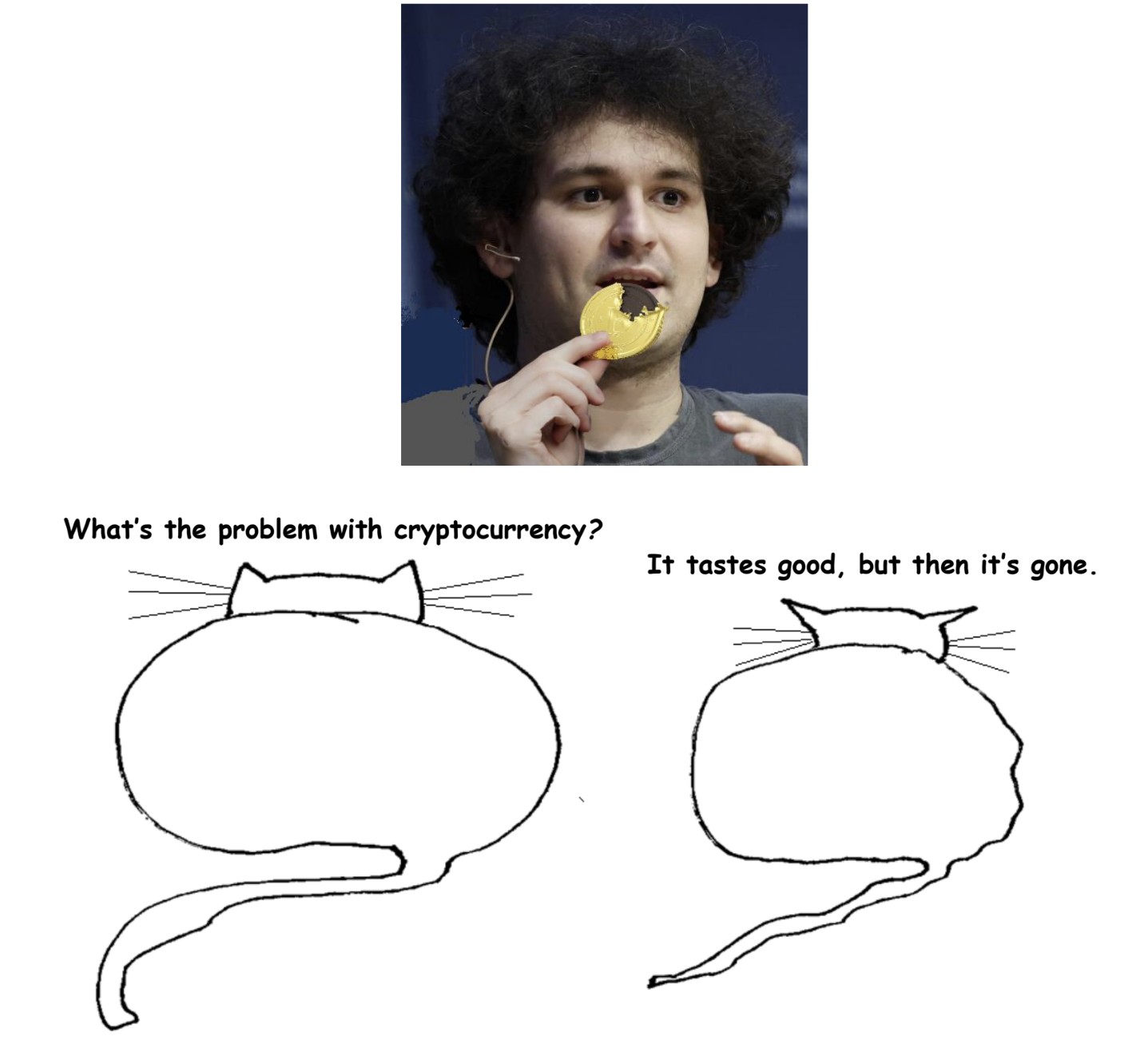

In debates about hedonism and the role of pleasure in life, we too often associate pleasure with passive consumption and then complain that a life devoted to passive consumption is unproductive and unserious. But this ignores the fact that the most enduring and life-sustaining pleasures are those in which we find joy in our activities and the exercise of skills and capacities. Most people find the skillful exercise of an ability to be intensely rewarding. Athletes train, musicians practice, and scholars study not only because such activities lead to beneficial outcomes but because the activity itself is satisfying.

In debates about hedonism and the role of pleasure in life, we too often associate pleasure with passive consumption and then complain that a life devoted to passive consumption is unproductive and unserious. But this ignores the fact that the most enduring and life-sustaining pleasures are those in which we find joy in our activities and the exercise of skills and capacities. Most people find the skillful exercise of an ability to be intensely rewarding. Athletes train, musicians practice, and scholars study not only because such activities lead to beneficial outcomes but because the activity itself is satisfying.

I’m excited about the imminent Halloween publication date of

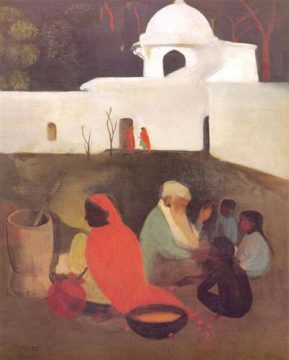

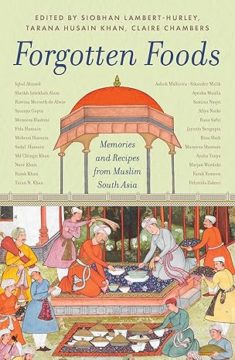

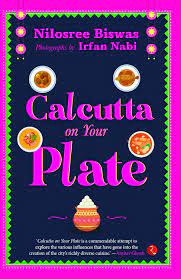

I’m excited about the imminent Halloween publication date of  South Asian literature. As part of this, I was delighted to be sent

South Asian literature. As part of this, I was delighted to be sent