by Jochen Szangolies

Recently, the exponential growth of AI capabilities has been outpaced only by the exponential growth of breathless claims about their coming capabilities, with some arguing that performance on par with humans in every domain (artificial general intelligence or AGI) may only be seven months away, arriving by November of this year. My purpose in this article is to examine the plausibility of this claim, and, provided ‘AGI’ includes the ability to know what you’re talking about, find it wanting. I will do so by examining the work of British philosopher and logician Bertrand Russell—or more accurately, some objections raised against it.

Russell was a master of structure in more ways then one. His writing, the significance of which was recognized with the 1950 Nobel Prize in literature, is often a marvel of clarity and coherence; his magnum opus Principia Mathematica, co-written with his former teacher Alfred North Whitehead, sought to establish a firm foundation for mathematics in logic. But for our purposes, the most significant aspect of his work is his attempt to ground scientific knowledge in knowledge of structure—knowledge of relations between entities, as opposed to direct acquaintance with the entities themselves—and its failure as originally envisioned.

Structure, in everyday parlance, is a bit of an inexact term. A structure can be a building, a mechanism, a construct; it can refer to a particular aspect of something, like the structure of a painting or a piece of music; or it can refer to a set of rules governing a particular behavioral domain, like the structure of monastic life. We are interested in the logical notion of structure, where it refers to a particular collection of relations defined on a set of not further specified entities (its domain).

It is perhaps easiest to approach this notion by means of a couple of examples. Read more »

A little over a year ago I published

A little over a year ago I published  Eddie Rodolfo Aparicio. White Dove Let US Fly, 2024.

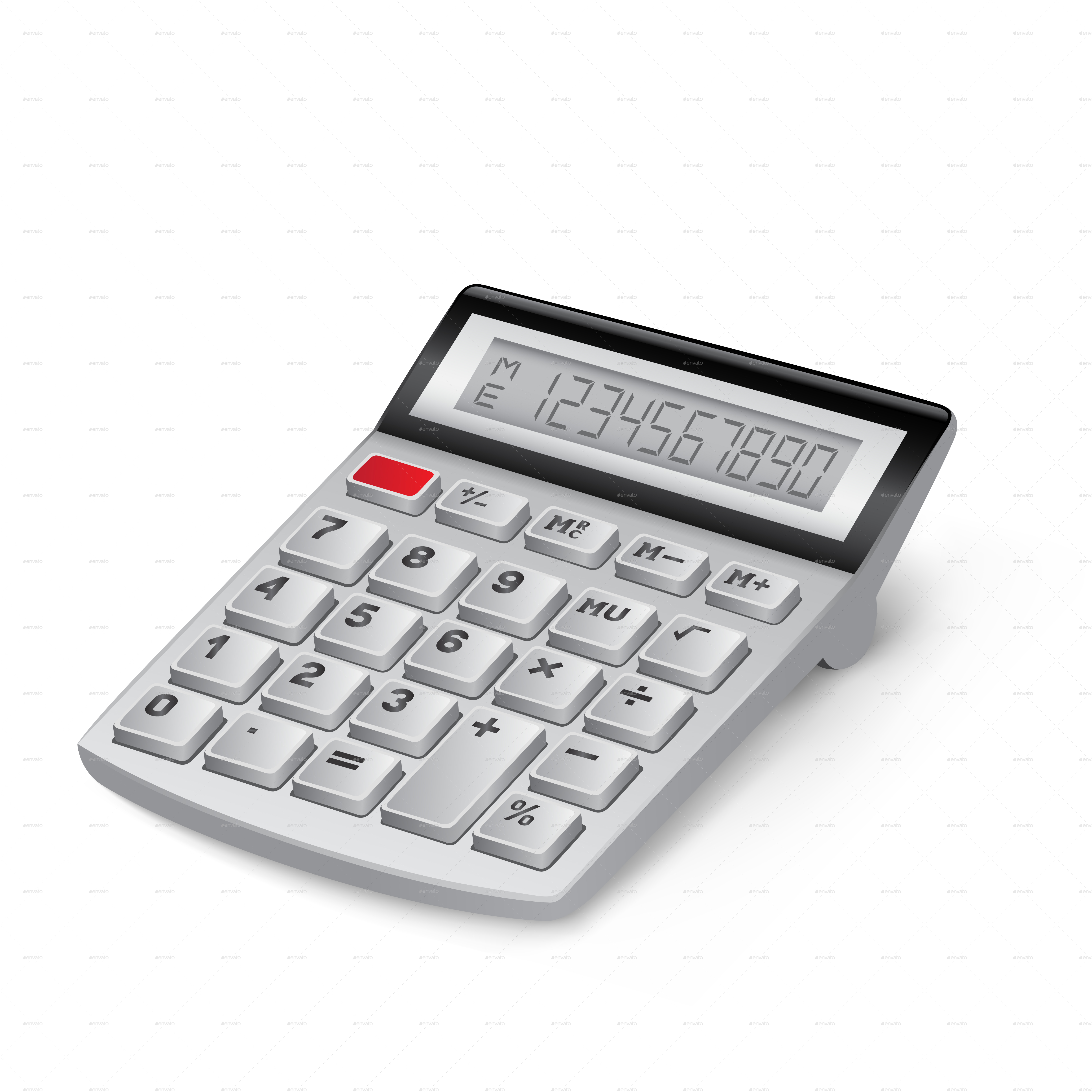

Eddie Rodolfo Aparicio. White Dove Let US Fly, 2024. “You are aware”, I ask a pair of students celebrating their fourth successful die roll in a row, “that you are ruining this experiment?” They laugh obligingly. In four pairs, a small group of students is spending a few minutes rolling dice, awarding themselves 12 euros for every 5 or 6 and ‘losing’ 3 euros for every other outcome. I’m trying to set them up for the concept of expected value, first reminding them how to calculate their average winnings over several rounds, and then moving on to show how we calculate the expected average without recourse to experiment. It would be nice, of course, for their experimental average to be recognizably close to this number. Not least since this particular lesson is being observed by the Berlin board of education, and the outcome will determine whether or not I can get a teaching permit as a foreigner.

“You are aware”, I ask a pair of students celebrating their fourth successful die roll in a row, “that you are ruining this experiment?” They laugh obligingly. In four pairs, a small group of students is spending a few minutes rolling dice, awarding themselves 12 euros for every 5 or 6 and ‘losing’ 3 euros for every other outcome. I’m trying to set them up for the concept of expected value, first reminding them how to calculate their average winnings over several rounds, and then moving on to show how we calculate the expected average without recourse to experiment. It would be nice, of course, for their experimental average to be recognizably close to this number. Not least since this particular lesson is being observed by the Berlin board of education, and the outcome will determine whether or not I can get a teaching permit as a foreigner.

Notational

Notational

A cinematographer would recognize this as a crane shot, or its replacement, the drone shot. This crane or drone doesn’t move. It defines the POV (point of view) of the painter, and shows how far his perspective can reach and how much he can cram into the in-between, that 2D surface which expands vertically with every higher angle of his POV, as in this crane shot from Gone with the Wind.

A cinematographer would recognize this as a crane shot, or its replacement, the drone shot. This crane or drone doesn’t move. It defines the POV (point of view) of the painter, and shows how far his perspective can reach and how much he can cram into the in-between, that 2D surface which expands vertically with every higher angle of his POV, as in this crane shot from Gone with the Wind.

Like many of us, they assembled an inordinate number of puzzles during the COVID-19 restrictions. And like many puzzlers, they came to wonder:

Like many of us, they assembled an inordinate number of puzzles during the COVID-19 restrictions. And like many puzzlers, they came to wonder: