by David J. Lobina

Like the study of any other complex idea, the analysis of nationalism requires building up boundaries between different phenomena, drawing various theoretical distinctions, and recognising the inevitable splits that arise within what may look like a whole ideology at first. It is by teasing out the building blocks of nationalism that we may obtain a better view, and it is by drawing attention to its psychological underpinnings that it might be possible to make sense of where nationalism comes from, both as an idea and as a real-life event.

Say what?

Well, this is a nice little summary of my general take on the phenomenon of nationalism, as laid out, from the perspective of linguistics, philosophy, and psychology, here, here, and here, and with a little help from the anarchist thinker Rudolf Rocker (here, here, and here).

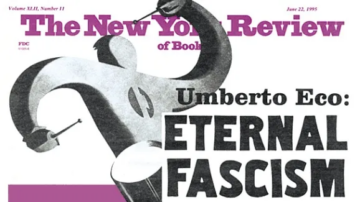

I am bringing this into play now once again as a way to provide the right segue to the long-promised conclusion to my series on the use and abuse of fascism to describe current political events, especially in the US (started here). It’s been quite a while since then, and there is a fair amount to pick up and discuss, and so I thought it would be in my best interest to write a sort of “refreshment” about what I was on about last time around.

The final-parter, which will double down on my original point – to wit, that the term fascism is used far too loosely these days, that most of the people it is being applied to are hardly fascists in any meaningful sense, and that modern political undercurrents bear little to no relationship to the European fascism of the 1920-30s, especially to Italian fascism – will come out next month and hopefully bring an end to the series (pending commentary forcing me to retake it later on, of course; actually, do comments still exist at 3 Quarks Daily? I haven’t seen any recently). Read more »

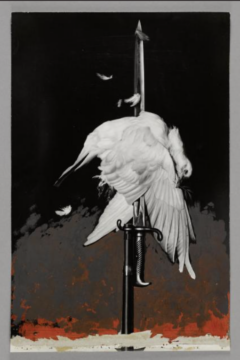

Raqib Shaw. Detail from Ode To a Country Without a Post Office, 2019-20. (photograph by Sughra Raza)

Raqib Shaw. Detail from Ode To a Country Without a Post Office, 2019-20. (photograph by Sughra Raza)

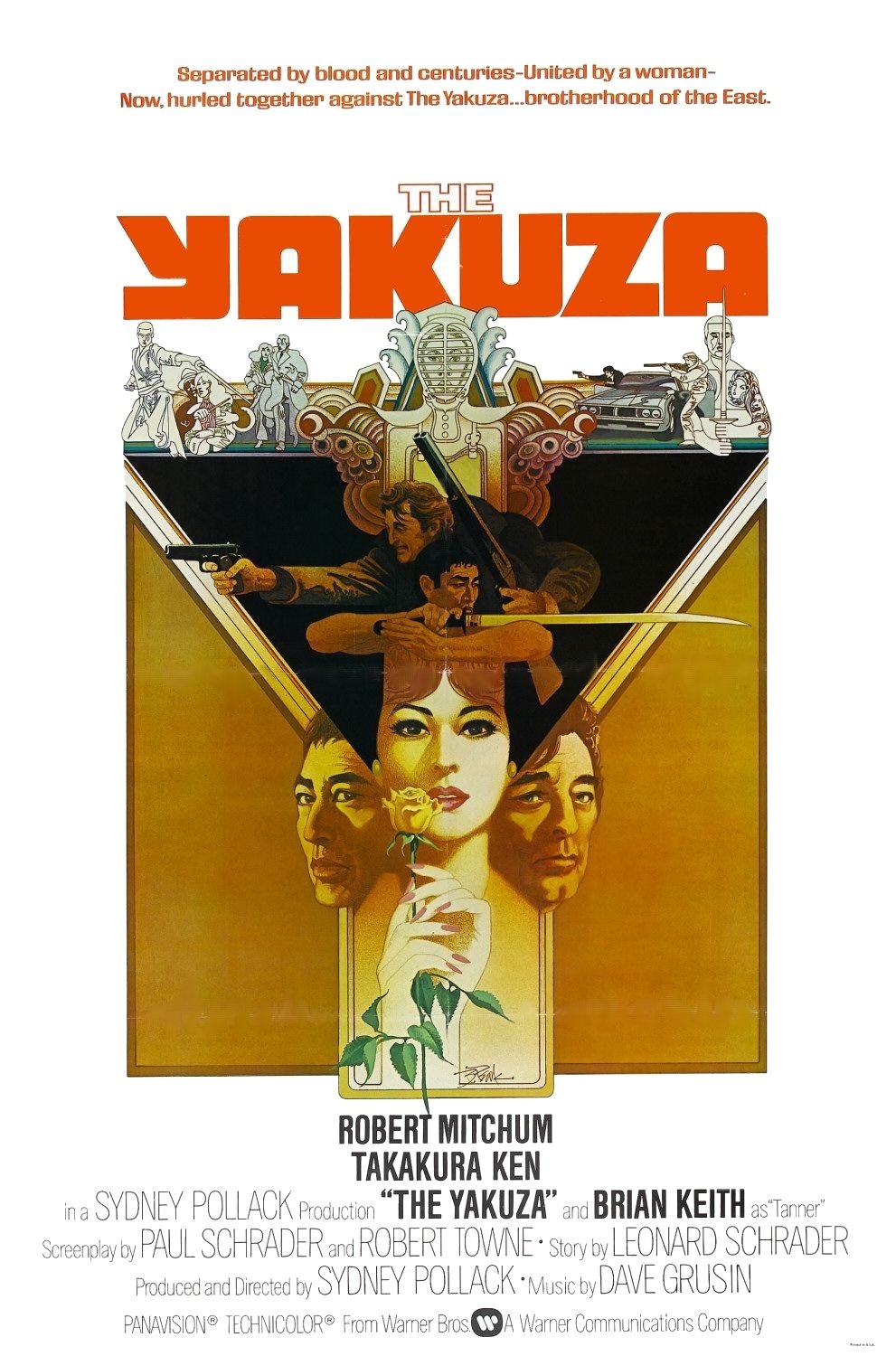

A few days ago I watched The Yakuza (1974), Paul Schrader’s screenwriting debut, and the following day I saw Andrei Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia (1983) at the cinema. These two films would never feature on a double bill together, and yet, due to having watched them within 24 hours of each other, they seem related in my mind, and I can’t help but interpret Nostalghia in light of The Yakuza.

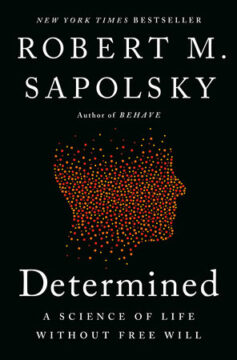

A few days ago I watched The Yakuza (1974), Paul Schrader’s screenwriting debut, and the following day I saw Andrei Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia (1983) at the cinema. These two films would never feature on a double bill together, and yet, due to having watched them within 24 hours of each other, they seem related in my mind, and I can’t help but interpret Nostalghia in light of The Yakuza. A few months ago, the Stanford biologist Robert Sapolsky released

A few months ago, the Stanford biologist Robert Sapolsky released

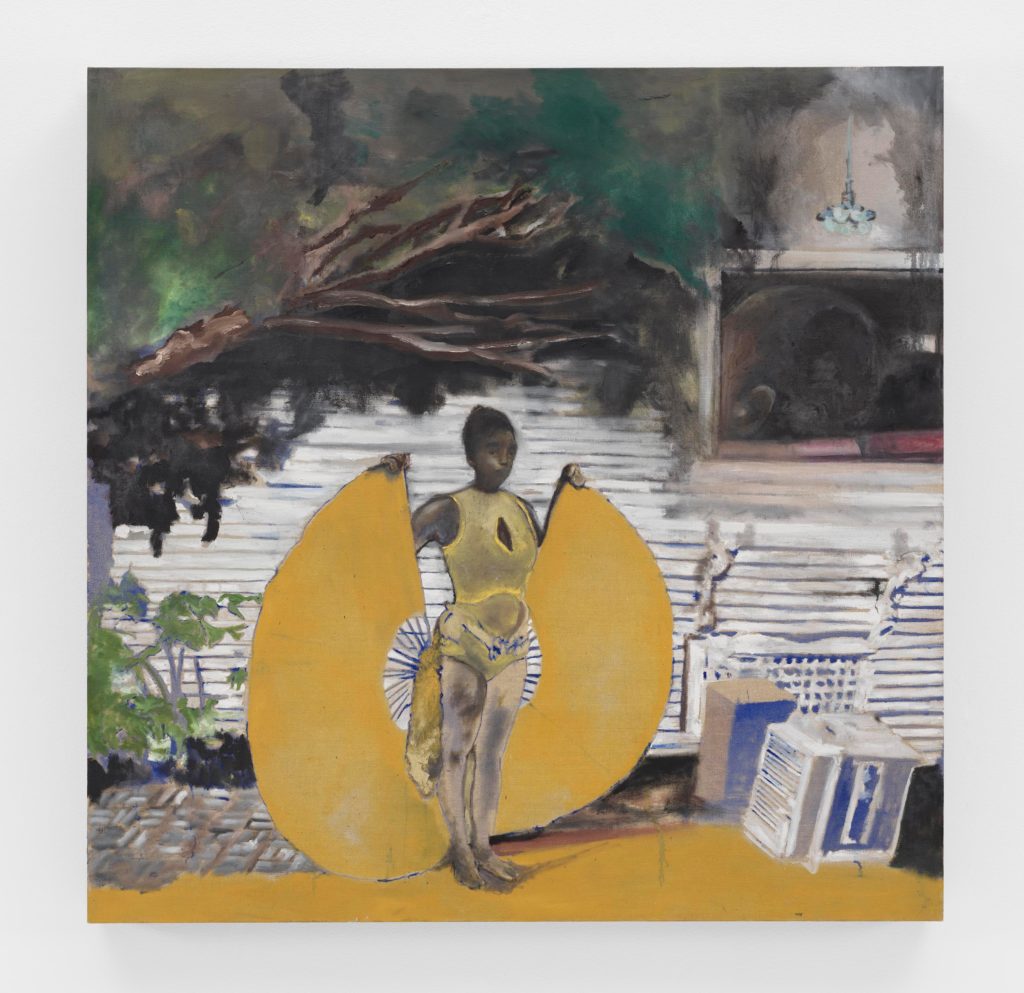

Noah Davis. Isis, 2009.

Noah Davis. Isis, 2009.