by Akim Reinhardt

The ChatGPT Bot has changed everything! That’s the basic vibe I’m getting from frantic press reports, early return think pieces, and even public-facing academicians. Specifically, this new, free AI software, only a few weeks old and still improving, is already churning out high school-quality essays on just about any subject a teacher might assign, and it now stands as a real threat to the very concept of high school and even college term papers.

As a History professor myself, I suppose I should be duly panicked. However, I don’t see the rise of the bot as something to fear or even resent. That’s not to say there isn’t cause for concern. There absolutely is, and adjustments are required. But my own personal history leads me to see charlatanism as something you simply have to deal with. Growing up in New York City, we learned to dodge it from a young age, with an understanding that it was up to us to spot it. Suckers may not deserve to get taken in a sidewalk game of Three Card Monty, as hustlers love to claim, thereby muddying their own immorality. However, even if the victims are to be pitied, suckers fill an ecological niche: they function as an object lesson to the rest of us: Don’t be like them. Don’t be a chump. I also wasn’t a very good undergraduate college student, though I didn’t cheat (too much pride, not enough giving a shit).

Add it all up, and I’m primed to stop cheaters. I know how a lazy student thinks, and I’m always on the alert, guarding against getting taken. I’ve also been designing and grading college student assignments for close to a quarter-century. So for me, this new AI bot is not scarey, or even revolutionary. It’s just the latest con for those who would seek to dupe me out of my most prized professional possession: passing grades. A quick rundown shows how the academic bunko game has changed just in my time as a professor.

-Classic Plagiarism: When I began teaching in 1999, the internet existed, but it was so rudimentary and access so sporadic, that most cheating on a paper was still what it had always been: either lifting passages from physical books and articles, or getting a bit too much help from someone else, a fellow student, friend, or even parent (trust me, it happens).

-Early Internet Plagiarism: Cut and paste was the name of the game during the early ‘00s. And it was easier than ever before with the advent of search engines. Students would fumble around, find something, copy sections, and paste them into their paper.

-Recent Internet Plagiarism: Buy a paper from one of the countless websites that soon specialized in such things. The more nuanced sites would even ask you if you wanted an A paper, a B paper, or a C paper. Make it believable.

Schools made adjustments. The biggest was purchasing new plagiarism-detection software. At first, these new tools weren’t very good, but they improved over time. One technique is to build a vast data base to catch purchased papers that are recycled. Most are. Sites typically sell the same papers over and over to new waves of students. Eventually then, the database becomes effective, even if it’s always a bit behind.

Some sites, however, began also selling brand new custom papers written by freelancers. Disgruntled grad students and even PhDs looking for a quick dime and some kind of payback while/after enduring an exploitative university system? Clever undergrads who needed the money or the ego boost? Either way, the data base software could not flag these original papers. So the software improved. Current versions also do extensive searches of the internet and compile composite data.

As helpful as these programs eventually became, they needed time to develop. Furthermore, colleges and universities, like most institutions faced with external attacks, can be slow to react. Thus, whenever a new round of plagiarizing techniques developed, instructors really had no one but themselves to depend on. For example, in the early days of the internet, that meant running suspicious passages through search engines.

But even when software caught up, some forms of plagiarism remained technically undetectable. We still have no way of proving a paper has been purchased if it is an original, tailored piece. We probably never will. And this is the not-new, existential threat AI fosters: that it’s getting easier to plagiarize and harder to catch plagiarism. It’s why a recent, hysterical headline from The Atlantic fretted that “Nobody is prepared for how AI will transform academia.”

Fuck that. I’m ready.

First of all, we’ve already got counter software. Here’s a GPCchatbot detector called Hugging Face.

And here’s a woman with Corgi stickers on her laptop offering a tutorial on how to beat Hugging Face.

Things move fast these days. The eternal cat and mouse game between swindlers and cops continues. But that concerns the external stuff that instructors can use to help them in their endless quest to catch cheaters. The most effective techniques, however, often come from the professor herself, not from the tools her employer or various businesses supply. Each professor, if they are to be effective, must think about the methods they will employ to preclude cheating, and how to punish it when it does occur.

When it comes to cheating in college, I believe the old adage applies: an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. But both prevention and cure are needed. So first, make it difficult for them to cheat. Second, when you catch them (and eventually you will), don’t rely on just one form of punishment. Have several options at your disposal, applying the one that best fits the specific type of evidence you have that fraud has been committed. More on that below.

The first step is making all of this very, very clear to all of your students on the first day. Don’t cheat. If you cheat, I will fuck you up. Don’t cheat. I have ways of catching you. Don’t cheat. Let’s go over the university policy on cheating. Look here; it says the university will fuck you up too. Don’t cheat.

Of course, use the language and tone that works best for you. I prefer to hold the various hammers up for them to see and show them my eyes, letting them catch the glint of overhead fluorescent lights on my irises, so they can imagine how they will glisten when I drop one of those hammers. But you do you. The key is clear communication. That they understand you are on top of it and will not put up with it. That you will probably catch them and there will be very serious consequences. If they can’t pass without cheating, they’ll know to withdraw and register for some other course with a doddering octogenarian who mostly smiles, hands out easy A’s, and still doesn’t know how to use a scanner, much less plagiarism detection software.

Beyond up front communication, I find that the key to good cheat-prevention comes in the sound design of assignments. For starters, consider doing fewer classic papers and take home essay exams. If we’re behind the curve at the moment (don’t worry, the pendulum will swing), then consider swapping out classic papers for other assignments they can’t cheat on (at least not that way). Oral exams can make for invigorating interactions with students, and are deeply appreciated by those who speak better than they write. As a grader, I find them to be a nice change of pace. The in-class offshoot of this is the formal presentation, which is an excellent way for them to develop a skill set that’s often ignored in college courses. As for written alternatives to the classic paper, in-class assignments come in many forms. Of course the age-old version is simply an exam. If you want it to function more like a paper, make it open book. Other writing assignments include reactions to the day’s lesson and lower stakes quizzes.

I could go on and on. If you are a college instructor, you could no doubt add assignments I’m not familiar with (I’d actually love to hear about them in the comments section). The point is that, it’s the classic term paper that is really susceptible to AI cheating, and there are many other types of assignment that are not (or not nearly). Younger instructors are better at recognizing this; it’s the Gen X and Boomer profs, who grew up on a steady diet of collegiate and graduate term papers and blue book exams when they were students, that perhaps need to think harder about being creative in the realm of assignments.

The bottom line is this. The harder you make it for them to cheat, the less they will cheat. Thus, prevention is not only the most effective means to stopping cheating, it also stems from the instructor’s agency instead of relying on, or even considering, the students’ ethics. Sound prevention techniques work well, strengthen professorial design, and place students out of harm’s way.

But even if the prevention is ten times more important than the hammer, the hammer is still important. Or should I say, the hammers. Each case demands individual attention. Sometimes a student cheats and gets caught. Fail them on the assignment. Fail them for the entire course. Report them to your school and begin whatever official process comes next. If you let a real cheater off easy, then you’re simply teaching them that cheating pays, and they’ll almost certainly keep doing it. It’s unfair to the students who don’t cheat. It’s also bad for all your fellow professors by not taking the steps that might reasonably prevent this student from cheating down the road in their classes. It’s deeply unpleasant, but do what needs to be done.

Then again, sometimes a freshman has been trained poorly (or simply didn’t pay attention in high school) and unknowingly plagiarizes. I know, it sounds like the student’s lying, and sometimes they are. But sometimes they are not, and you can probably tell. Honest mistakes do happen. Either way, the point is that you handle each case whichever way you feel you need to handle it.

But disparities aside, what to do with the student who you know deep down in your bones has plagiarized a paper, perhaps with this new goddamned bot, or maybe with a tailor-made paper they paid for, but either way, you cannot find any smoking guns?

Nail ‘em.

Oh, you can still do it. Even though you can’t prove plagiarism, you can still fail them for assignment, and possibly even the entire course. But you’ve got to be prepared.

The key is recognizing that plagiarism is just one example of academic dishonesty. They’ve plagiarized and you can’t prove it? Show that they’re academically dishonest and go from there. Here’s how it works.

It begins with the syllabus. About fifteen years ago, when the tailor-made papers were becoming more common, I came up with this approach, and I had my then-department chair run it by university council. They said it was copasetic, and I still use it. In the syllabus section where I talk about academic dishonesty, I include the following:

You, the student, are solely and fully responsible for all of the intellectual property that you present in this course. If you are incapable of claiming responsibility for intellectual property that you present as your own, the instructor retains the right to deny your ownership of it and any credit, rights, or privileges that your ownership would convey.

What does this mean? That if you submit a paper and it smells fishy, I’m gonna call you into my office, have you read some selected fishy bits, and then discuss them with you. Break this down for me. Explain that concept. How did you arrive at this conclusion based on the evidence you provide? That’s a fun word, what does it mean? And so forth.

If they cannot do so to my satisfaction, they get a zero for the assignment. Not an F, but a zero; all my assignments are graded numerically, so all F’s are not created equal. Thus, depending on the value of the assignment (and if a term paper, it’s likely sizeable) they’ve probably also just bombed the entire course.

This works. You can fail them when they’ve plagiarized but you can’t prove it, because they don’t really know what they’ve “written” and therefore will fail to clear basic academic bars. Can they appeal? Sure. How will that go? Not well for them. If you had a qualified witness at the meeting (your chair, another professor, etc.), then there’s nowhere for them to turn. That’s two people testifying that they botched it to the Nth degree. Even if you didn’t have a witness, your testimony on the student’s failure to claim their intellectual property might very well hold up down the line. And either way, tales of such misadventures work as excellent prevention on Day 1.

Let me close with a personal shortcoming. Not a tale of hypocrisy, but a sad admission that I do not always follow my own advice.

Let me close with a personal shortcoming. Not a tale of hypocrisy, but a sad admission that I do not always follow my own advice.

This past semester I had a student plagiarize two one-page papers. It came late in the semester, and based on the student’s performance up to that point, I believed there’s absolutely no way the student authored those two short papers. Yet I let it go.

I did inform the program director of the situation, who in turn encouraged me to report it. But the student was already struggling in the course and about to flunk out of the program. I also liked the student, whom I thought was a decent person in a bad position through no fault of their own, and in over their head. So I took the easy way out. I issued a bad course grade, based strictly on total course performance, and left it at that. Because despite all my big talk about hammers and such, I can be rather conflict-averse. And so in this instance I did not do what I should have done. And that’s what’s so terrible about cheating, in any form at anytime.

Yes, once in a rare while it’s being perpetrated by some sociopath; some future chiseler whom you’re genuinely happy to screw to the wall in the interest of helping humanity; some utter fraud like George Santos who will claim he graduated from your school even if he didn’t, so get him good. Or even some lower level prick, not a grossly terrible one, just lazy and unethical, looking for shortcuts. Or even the odd thrill-seeker who craves the rush of getting away with it. Get a nice, big hammer.

But in my experience, these are not the most common cheaters. Usually, cheating is born of desperation. The fear of feeling it all collapse around you, for whatever reason. It’s often the last grasping effort to keep one’s head above water. As much as we enjoy the story of a good hustle, I think most people, certainly most college students who cheat, do so to keep from going under. Because they’re afraid.

And that’s the real reason why dealing with this stuff is by far the worst part of the job. If the best thing about teaching is seeing that light bulb go on over a student’s head, then this is the exact opposite of that. It’s a descent into human fear and misery. It’s witnessing the wrong kind of surrender.

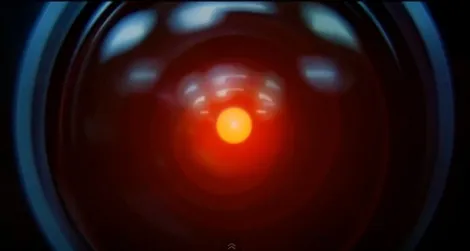

Computer, write a short essay discussing the fear and sadness that drive cheating and imbue the process of uncovering it.

Akim Reinhardt’s website is ThePublicProfessor.com. It’s the worst chat bot ever.