by David Winner

Coming from a Jewish family that arrived in America between the Slave Trade and the Holocaust, I thought that we were ethically in the clear, but researching my family story for Master Lovers, a book about my great-aunt Dorle’s love life in the 1930s, brought me face to face with famously fraught questions about evil and prejudice and the degree to which art and/or historical context can relieve us of its burdens. I thought of Ezra Pound’s and T.S. Eliot’s fascism, of course, Dustin Hoffman, Keven Spacy, and all the other actor/molesters but also Alice Walker’s interrogation of the Talmud, antisemitic or simply pro-Palestinian. And V.S. Naipaul, Indian from Trinidad, whose work (Bend in the River, India: A Wounded Civilization) skewered the post-colonial world.

Dorle Jarmel Soria, a Jewish woman who was a force in mid-century music, integral to both Leonard Bernstein and Maria Callas’s careers, and her husband Dario, who’d fled Rome after the Mussolini/Hitler pact, essentially raised my father. Once, he questioned Dorle about her friend soprano Elizabeth Schwarzkopf’s, close relationship (maybe affair) with Goebbels only to be rebuffed by the claim that “great art” lay “outside of politics.” And learning more about both her family and her lover, John Franklin Carter, whom she nearly married, revealed more dark associations. Ben Affleck convinced Henry Louis Gates not to reveal his enslaved-owning ancestors, but I – unfamous, little to lose – feel driven to out my family. Dorle, who smoked Benson & Hedges, drank gin and tonics, and traveled to Capri well into her nineties always recalled Graham Green’s beloved Aunt Augusta (Travels with my Aunt), but learning more about her made her seem more like Aunt Denver from Beloved, Heathcliff perhaps, someone haunted by their past.

By age thirty, I knew only a few “facts” about my Jewish family: our name did not come from Weiner, we were from somewhere near Poland, a distant relative translated the Declaration of Independence or was it the Constitution into Hebrew or Yiddish. Whereas my mother’s mother, born in Hapsburg Prague, compiled a genealogy going back centuries, my father’s Jewish side was apparently the family who fell to earth.

But one afternoon in 1995, Angela, my then-girlfriend/now spouse, glimpsed the letters “S. Jarmulowsky and Sons” emblazoned on a grand old building on Canal Street in Chinatown and intuited a connection to Dorle Jarmel. In the AIH Guide to New York, we learned that the building had been involved in a painful chapter of New York Jewish history, which due to what historian, Tony Michels, has called “Jewish Triumphalism” has been largely forgotten.

The troubling family tale had a Horatio Alger beginning. Sender Jarmulowsky, who turned out to be Dorle’s Grandfather, was orphaned in a cholera epidemic in (yes!) Poland. He became a rabbi and businessman, living proof according to the Yiddish newspaper, Morgan Zhurnal that, “in America one can be a rich businessman but also a pious Jew.” He created a shipping line in Hamburg and later the bank on Canal Street responsible for bringing nearly half the Jews to the Lower East Side from Europe and holding their accounts, making him famous throughout New York and the Pale of Settlement.

But when his son Louis (Dorle’s father and my great-grandfather) and his brother Meyer took over, they used depositor’s money to buy buildings in Harlem. According to historian Rebecca Kobrin, they engaged in racist redistricting, redlining. While not involved in the slave trade like Affleck’s ancestors, my family deprived African Americans of a chance to gain the real estate equity that has been the traditional path to the American middle class.

When World War One approached, account holders took out money to send to relatives in Europe. With so much capital locked up in real estate, the bank collapsed, wreaking financial havoc on the Jewish Lower East Side. Some depositors committed suicide. One depositor almost killed Meyer, and many others rioted outside of Dorle’s uptown apartment building, forcing her and her family to escape to the roof.

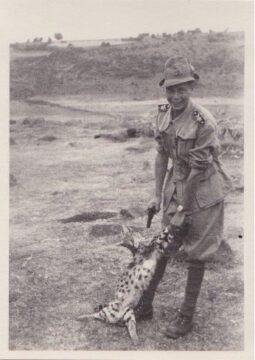

The collapse of the family released Dorle and her sister, Faie, my grandmother, from traditional female Orthodox Jewish roles, allowing Dorle to be a publicist and Faie, a shoe designer. But neither sister ever relayed the shameful story to later generations. Dorle and Faie’s disquieting family history recalled other unsettling family photographs: Grandfather Percy standing next to Mussolini, whom he’d interviewed, the first American to do so, Uncle Dario, an officer in the Italian Fascist Colonial army, standing over a cheetah he’d shot in Eritrea.

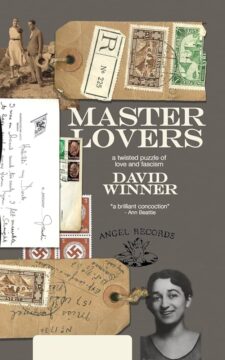

Fascist tendencies weren’t unusual in that era. Mussolini’s approval rating (long before the term) was sky-high in Italy, and probably higher in America than either Biden’s or Trump’s now. But more surprises were in store when I was tasked with clearing out Dorle’s apartment after her death. First, I found Master Lovers of the World, a book Dorle wrote in her teens romanticizing problematic figures like Henry Vlll: “no monster but a powerful generous man with gold hair and beard, penetrating blue eyes and a ruddy face,” and then, like a companion piece, five sets of hidden love letters from different men in the 1930’s. John Franklin Carter, who wrote her hundreds of them, was known as a reporter and FDR apparatchik. Still, when I plugged his name into the New York Times archive, I found the following from 1932: “John Franklin Carter, a young American now traveling in Europe, has been appointed chairman of an organizing committee for a New National Party that is to introduce Hitlerism in the United States.”

I walked around for months believing that not only had my great-grandfather helped deal a lethal blow to poor New York Jews, but my great-aunt had had a long affair with a married Nazi. Antisemitic tropes of Jews sticking together may have been blown, but I felt tainted, nauseated. I thought of Hannah Arendt and the “banality of evil,” and wondered if Dorle exemplified “the inability to think.” Was her connection to Nazis and the Nazi adjacents due to “thoughtlessness as well as stupidity?”

I poured through Carter’s letters to Dorle, struggling with his handwriting, but found no reference to a Nazi party. And Arthur Sulzberger, publisher of the New York Times, wrote Carter to reluctantly walk back the claim that he ran one, but Carter’s politics remained suspect. When Puzi Hanfstaengl, Hitler’s press secretary, took John and his wife Sheila to see Hitler speak in Munich in 1932, Sheila declared it “quite a good show,” in her diary. “All of Berlin,” she wrote admiringly when Putzi brought the Carters up to Berlin, “feels electric over the showdown in Reichstag- where all the traffic has been stopped, heavy police guards posted.”

John also wrote Dorle about encountering a friend named George Viereck, “the top banana” of German infiltrators in the lead-up to the Second World War, according to Rachel Maddow’s 2022 Ultra podcast.

Viereck suggested to Carter that he might be on the congressional list of suspected Nazis. He wasn’t, but I still wondered how I should judge Dorle for the company she kept, how I should cast her in Master Lovers, my book about her and her lovers.

Around 2000, the tour guides at Monticello, Jefferson’s home up the mountain from Charlottesville where I grew up, finally stopped erasing his (and our) original sin by calling where the enslaved lived, “servants’ quarters.” The Confederate statues in town were also removed though at the cost of Heather Heyer’s life – 2018, Unite the Right. With Virginia in mind, I wondered how I could address my own family history. I don’t have the tools (or guts) to tear down the insignia of the family bank, but I could interrogate the narrative of Dorle’s life. In early versions of Master Lovers, I sentimentalized her. “Amazing woman,” polite readers would tell me, “great lady,” but I kept revising, trying to cast her as the ethical anomaly that I think she was.

An earlier novel of mine, Tyler’s Last, involves fictional versions of Patricia Highsmith and Ripley. Generations of readers gave Highsmith a pass. But I tried to reveal her antipathy to Jews, black people, and Puerto Ricans, who, according to the sympathetic protagonists of The Dog’s Ransom, were ruining 1970’s New York, by using close third narration to place prejudice in her mind. I placed troubling thoughts in Dorle’s head too, though, she was less an open racist than a tolerator of evil. Dorle’s version of Paul Gauguin, for example, written when she was eighteen, encountered his great love “in a blue stream against a background of lime and mango trees, only thirteen, but a woman by Tahitian standards.”

“In the man’s man’s man’s world” in which Dorle lived, she often fought off sexual assault, once at the hands of conductor Werner Klemperer, the father of the man who played Colonel Klink. Unfazed, she turned it into cocktail party fodder and would have likely been unsympathetic to #metoo as she believed that women could always resist.

After Elizabeth Schwarzkopf’s deeper Nazi ties were revealed late in Dorle’s life, I asked her my father’s question. Yes, she said, it bothered her. She had grown more empathetic as she’d aged. I wonder how she would have responded to questions about John Franklin Carter. Or other Nazis she’d known in America and those that she did not in Poland, where members of our family must have died in the Holocaust. When black soprano, Leontyne Price, was asked to take the service elevator to Dorle’s apartment in the early sixties, she and Dario expunged that policy, but racism, sexual harassment, and antisemitism may have seemed immutable, not worth fighting. Her own family was implicated, after all.

What about me, though, still around decades later? I must own Dorle’s history as I’ve tried to do something that she never did herself, which is to tell her story.

Dorle took many ships to Europe and the Middle East in the thirties, and I have inherited her travel bug. The summer of 2023 found me wandering gleefully around Bucharest, marveling at the sculpted angels and goddesses on the early twentieth century buildings amidst old Orthodox churches and socialist monoliths. A quick dip into my phone to learn the Romanian history of those eras brought me right back to Dorle and the Jews. While Romania may not be notably worse than many countries in Europe, violence towards Jews and Roma was inextricably linked to its history.

As an expiation of a sort, I sought out Bucharest’s two Jewish museums, hoping to find the city accurately telling those stories like Monticello has in more recent times. The museums are located in the old Jewish quarter, which, like much of the city, had been razed, socialist-era apartment buildings put up in their stead. The first address had no museum at all, and the second museum, dedicated to the Holocaust, was inexplicably closed.

Sitting on a bench in front of a small memorial, I thought about the Jews who’d lost their lives, as well as the other Jews, some from Bucharest, who’d lost their money in the family bank. “What can I say,” a phrase that my therapist, the daughter of Ukrainian Holocaust survivors herself, is wont to say when the answer is nothing.

In America, structures have often been built over the graveyards of the indigenous and the enslaved. New resorts in Maui are likely to do the same. We can’t always avoid such places as we don’t always know where they may lay, but we can try to listen for the voices of ancestors, not just our own. Those who suffered. Those who caused suffering. Evil runs in the best of families.