by Bill Murray

First a note on the April 8th North American eclipse: Many people have seen a partial eclipse of the sun and wondered what all the fuss is about. The sky looks out of whack, things go all shimmery, you can see reflections of the partially occluded sun on leaves, animals act up, the sky darkens, maybe, and then it’s done.

That is a partial eclipse. The experience inside the narrow band of earth where the sun is entirely covered, called “totality,” is nothing like a partial eclipse. Two weeks from today North America experiences the longest path of totality for any eclipse this century.

The band of totality will be about 115 miles wide. Lots of people have the chance to get underneath it. If you’re interested, don’t settle for partial; go and find totality.

The longest totality in the US will be four minutes and 24 seconds. By comparison, the longest totality anywhere in the US for the 2017 eclipse lasted only two minutes and 41 seconds. These may sound like just statistics, but nearly five minutes of totality is a big deal. People pursue even a minute of totality across continents.

Totality is utterly unique. It’s something else entirely. Totality pulses with raw, brute, human-diminishing power.

Outside totality, the sun is such a monster that light blasts right around the disk of the moon and, as you have seen if you have witnessed a partial eclipse, the earth is little changed. In totality you witness physical forces heaving massive objects (the moon!) across the heavens. You can not but be awed by the delicacy of the dance, the wispy, exact fit of the moon over the sun, the clockwork, the elegance of the ballet, the notion that this is impossible, but it is happening.

Totality is fiery anger. It fills the world. It is utterly spellbinding. It scales your body to tiny, but broadens your spirit and calls you up into the sky. The sun’s aurora is delicate, its airiness calls forth humility and awe. You fall mute with its silence, for if you shout you might break it.

Viewing totality – and this is a good, long totality – will change how you see the world. It is surely the best glimpse of the universe beyond earth you’ll ever get short of leaving the planet. If you can, on April eighth, go and experience totality.

•

OFFSHORE FROM PORTUGAL TO CAPE TOWN

Everybody agrees the Madeira archipelago off northwest Africa is magnificent, a gorgeous bit of earth. Twelve hundred miles to the south, a small island called Sal, isn’t. It’s flat, twenty miles long and part of the Cabo Verde archipelago west of Senegal. My impression from once refueling there in the middle of the night: moonlit desert island. Nothing but sand, shore to shore. Exotic? Maybe. But lovely? Surely not.

The dozens of isles, atolls, skerries, specks and pockets of land that hug Africa’s shores support every kind of flora, fauna, marine and human life, and widely divergent geography. There is every kind of delight to be found around L’Afrique Périférique, and people know far too little of it. Let’s take a tour.

Since Portugal led the European colonial sprint down the African coast, let’s start there, at the edge of Europe, in a small, lush group of islands called the Azores, a part of Portugal far out in the Atlantic.

Visitors enjoy the expansive water horizon, the tamed and farmed landscape and a not very European, relaxed rhythm. The Azores’ population density is over three times that of Portugal but you’d never suspect it. There is room to breathe, the air is fresh and if you’re ten minutes late, well, what’s ten minutes?

The Azores were uninhabited before the Portuguese arrived, so they settled the place and grew grape and grain, and the Azores served as a staging station for westbound exploration in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, and as a support base for whalers.

Now southbound: Portuguese Madeira lies much closer Morocco, as do the Spanish Canary Islands further south. Europe and Africa both pull on Islas Canarias, advantage Spain, which staged a conquest of the islands in the 15th century against the fierce resistance of the indigenous population, Guanches, descendants of Berbers. Thirty or forty percent of Canarians have Guanche genetic heritage.

I have found one other populated island off Morocco, a place called Mogador, home to about 700 people today, a mile opposite the fishing town of Essaouira. While some say it traded with sailors from as far away as Carthage in years BCE, today it is a nature reserve and you can’t visit without official authorization.

Down the Mauritanian coast islands, and people, are sparse. A few small islands host seasonal populations, nomadic fishermen, but climatic harshness and the decided lack of regional dynamism conspire against more permanent development.

I mentioned Sal, the sandy island that’s part of the Cabo Verde archipelago, something more than 400 miles off Mauritania. These are volcanic products of the mid-Atlantic ridge, some with calderas, cones and lava fields. They are said to support rich marine biodiversity, vibrant coral reefs and even a few fertile interior valleys. Fishing accounts for about 80% of Cabo Verde’s exports, although the most treasured national export surely remains the late singer Cesaria Evora.

Beyond Mauritania

All day long, ferries ply the short distance from Dakar to Gorée Island, perched just off the coast of Senegal. Infamous for its slave trade, Gorée, like, among others, São Tome and Principe, Ouidah in present day Benin and Bonny Island, Nigeria, was used as a staging point for the so-called Middle Passage. At its height in the late eighteenth century, twenty or thirty thousand slaves shipped out below decks and in shackles every year.

Besides Gorée, in Senegal I can only find two tiny inhabited islands, Île de Ngor and Île de la Madeleine, both a fraction of a square mile, each a few hundred people fishing or manning salt pans.

Two hundred thirty miles south of Dakar the Geba River flows 270 miles from highlands, to open offshore onto the Bijagós archipelago, some of the most beautiful islands most people will never visit. Of some 88 islands and islets, twenty, so they say, are home to vibrant communities, some matriarchal, where women propose to men and have the final word on divorce.

There’s an unpaved airstrip there at a place called Bubaque (it has an IATA code: BQE) and a Spanish ferry company sails once a week from Bissau City, Guinea, on a schedule it posts weekly down at the harbor. Or you could catch a canoe from the mainland, as one tour site has it, “often overloaded, sometimes leaking, and always of questionable maintenance.”

Making the big eastward swing toward the Gulf of Guinea, packed barrier islands full of working folks line the Ivorian coast opposite Abidjan, then the islands that populate the Ghanian coast mostly support fishermen.

Past Nigeria, Bioko Island comes as a curiosity. Volcanic and sweltering a hundred miles offshore from Cameroon’s largest city, Douala, the main city on Bioko Island is Malabo, the capital of a different country, Equatorial Guinea. Yet most of Equatorial Guinea inhabits the mainland.

Everything’s funny about Equatorial Guinea. It’s a hardly governed, tiny land about the size of Slovenia whose oil and gas reserves put it at the center of an epic 2004 coup plot starring African governments, mercenaries and Margaret Thatcher’s son, Mark (who was a financier). The ringleader Simon Mann told the story in his memoir, Cry Havoc. Mann says Equatorial Guinea is a lawless, fetid backwater. I bet it is.

Next comes São Tomé and Principe, a sovereign island nation with a fading Portuguese colonial overlay, promoted to Europeans these days as resort islands, with two or three weekly TAP Air Portugal flights between Lisbon and São Tome. It’s just off the coast of Libreville, Gabon. The great majority of residents descended from Portuguese colonists and African slaves.

Undoubtedly, the most famous thing ever to happen there was British scientist Sir Arthur Stanley Eddington’s 1919 visit, which cemented Albert Einstein’s scientific star power, and is a timely story in light of next month’s solar eclipse. Einstein’s audacious four year old theory of relativity sorely needed testing. Relativity predicted that light should warp as it passes the gravitational field of an object in space, like the sun. But how to measure such a thing?

If light from stars behind the sun were bent by the sun’s gravitational field, those stars’ apparent position might be distorted so that they became visible. Their apparent position should be different from their normal position in the sky at night, when the sun is far away on the other side of the earth.

How can you see behind the sun? Perhaps with the help of the moon, during an eclipse.

On the morning of May 29 (eclipse day) there was a very heavy thunderstorm…. ”But “about half-an-hour before totality the crescent sun (partial eclipse) was glimpsed occasionally,” and in the end “16 (photographic) plates were obtained … by moving a cardboard screen unconnected with the instrument.”

Eddington compared a set of “true” positions of the stars – photos he had taken of the same patch of sky when the sun was nowhere around – with the set of photos he took during the eclipse. He could confirm Einstein’s theory.

The day after Eddington announced his findings back in Europe, the New York Times of 10 November, 1919, ran these headlines:

LIGHTS ALL ASKEW IN THE HEAVENS

Men of Science More or Less Agog Over Results of Eclipse Observations.

EINSTEIN THEORY TRIUMPHS

South from the middle of the continent a few inhabited islands cluster around Angola’s capital in Luanda Bay. Most of Angola’s other islands are uninhabited or just support temporary fishing camps.

Luanda and Walvis Bay, in present day Namibia, and then Cape Town, were the primary restocking stops on the local, coast-hugging route for discovery era Europeans bent on conquest. Both gave explorers access to fresh water and established trade networks.

These two towns, along with Swakopmund near Walvis Bay, the very small Luderitz farther south in Namibia, and a tiny settlement around a seal reserve and salt mining operation called Cape Cross, remain just about the only populated places on this very long part of the African coast. There are no human-inhabited islands off Namibia.

Islands Far Away

Well west of Angola, 1200 miles offshore, lie a pair of islands, St. Helena and Ascension. The inhabitants of St Helena, today a self-governing British Overseas Territory, revel in their identity as self-proclaimed “Saints.”

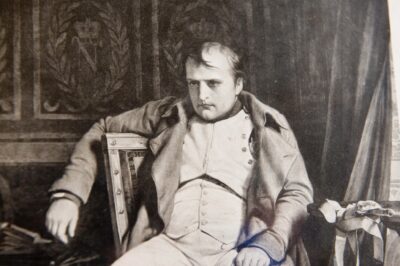

The Brits hauled Napoleon into his second exile (after Elbe) way out here. There is no chance that you will come all this way and not go and see Longwood House, where Napoleon lived and died in exile.

French journalist Jean-Paul Kauffmann was held hostage for three years in Beirut. That ordeal informed his book The Black Room at Longwood, written after his visit to St. Helena.

“Longwood,” he wrote, “together with the Valley of the Tomb, makes up the French enclave” on St. Helena, sold by the Brits to France after negotiations initiated by Napoleon III, for 178,565 francs.

Gracious and comfy, probably a little drafty in the cold, sturdy and low-key, its modesty calls to mind similar historical properties like FDR’s Little White House, and Höfði House, the site of Reagan and Gorbachev’s summit on the edge of Reykjavik. None of those three match in real life the mythic expectations attached to world leaders (Potsdam’s Cecilienhof Palace, host of Churchill, Stalin and Truman at the end of WWII, that one does, maybe.)

After about twenty years, I remember a jumble of experiences from visiting St. Helena, but one memory is most vivid – that of our arrival by sea. We’d been chugging up from Walvis Bay for three days and arrived at St. Helena (“Saint He – LEE – na”) in early morning from the south, sailing around to Jamestown in the northwest where the captain paused to take in the sight.

The haughty cliffs beside Jamestown cry out: “you cannot come here.” I expect they extend the same challenge to petrels, shearwaters, boobies or kestrels or puffins or any mountain goat who may arrive in error. No foothold, no claw hold, no place for your eggs. We cliffs of St Helena stand united to hold you back.

Ascension Island, farther beyond St. Helena, hardly feels African, or anything else. It’s home to British and American military bases, and no one lives there except on contract.

(Other islands are this way, like Svalbard, in the North Atlantic, where to become a resident, you need a demonstrable source of income sufficient to support yourself, and if you lose your job you’ll be packing it all back to Norway. Then there’s an archipelago called Kerguelen, far off the other side of Africa, which we will cover in time.)

I met a man named Nick on the two day run up from St. Helena to Ascension Island. The ferry was full of “Saints” like Nick, residents of St. Helena, on their way back to contract work up at Ascension. Nick had a shop in the village of Two Boats.

Nick and I sat drinking beer in the open air aboard the RMS St. Helena, out on deck behind the sun lounge. We were escaping the games inside, bingo and the like, meant to entertain passengers grown weary of no sight of land for a couple of days.

Nick spoke in quick half-sentences. He’d make a point and give a knowing nod and a smile, like he’d just heard himself and agreed with what he said. And he had some things to say:

“St. Helena got its problems, y’know? Some people makin’ a fortune. Guy goes off to the Falklands to work, lives almost like a slave. Livin’ in dormitories, cleanin’ up after the Brits. He gets free travel, now, but he makes what, five grand a year, comes home and a house gonna cost him twenty. No way to live.

And a man ought not have to go away to earn a living anyway. Here I go to Ascension, been there eleven years. Now the good thing: the way you can raise kids. It really is good. I’m bringin’ my son because I have a little shop and my wife, she teaches. No lockin’ doors, keys in the car. 900 people, maybe a thousand, right? Somebody ever takes something, eventually you find it.

Now I been eleven years on Ascension. I been lucky. Time for me to go back to my business on St. Helena. My father died young. Not young, 62. My mother died in her 50’s. Lucky, my Auntie keeps my business back home. Won’t say I’ll never go back to work on Ascension. You get really big fish there, you know?”

Still farther out in the Atlantic and worth mention for its utter obscurity, Tristan de Cunha would probably be claimed by no one if the Brits weren’t tagged with it. Instead St. Helena, Ascension Island and Tristan da Cunha share a governor, who sometimes visits Tristan de Cunha, just about halfway to South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands and more associated with Falklands and Antarctic cruises, by sailing from Cape Town aboard the MFV Edinburgh. MFV. That’s Motor Fishing Vessel.

A surely inbred place, Tristan da Cunha’s population stays about 270, sharing seven surnames. Sits some 1,750 miles from Africa. Supply boats from South Africa sail there less than once a month.

But Tristan de Cunha has a post code, TDCU 1ZZ, and writing in the Tristan Times, via the South Atlantic Remote Territories Media Association, someone called J. Brock tells us that “an item ordered over the internet (it’s not clear if it was ordered from the Island) reached its buyer” with that post code attached. Crawfish and postage stamps, that’s how they make their money. It’s not really much related to Africa, or anywhere else.

Portuguese Navigation Tricks

The Portuguese were first to round the Cape of Good Hope en route to India. In getting there, navidadores learned a neat trick: the fastest way east around the Cape was to sail west.

Prevailing winds and currents made hugging the shore tough. Some 1,000 shipwrecks up and down Namibia’s Skeleton Coast can testify. But by sailing farther out into the Atlantic, sailors found conditions that could effectively sling them around the Cape, as Bartolomeu Dias first accomplished in 1488.

(Sailing west that way played an unintended role in the eventual European discovery of Brazil and the new world. A fleet bound for India under the command of a Portuguese diplomat named Pedro Álvares Cabral sailed too far west and turned up on the Brazilian coast in 1500.)

But back to where we were. We’d gotten down the coast to Angola, and from there south to the Cape of Good Hope the coast is fairly desolate. Beyond Angola, early explorers mostly kept moving past Namibia and on around the Cape because outcrops, islands and archipelagos off Namibia’s Skeleton Coast are small, barren, uninhabited and offer little.

The Namib, the oldest desert in the world, stretches some 1200 miles north to south along shore. It’s almost completely dry. Some parts of the Namib get less than half an inch of rain a year, and have for the past 55 million years. So the human population is scant.

But here be seal and bird colonies, including colonies of the African penguin, and bountiful marine life. This non-human domain prevails, as far as I can see, right around to Robben Island, the only island of much size in Cape Town’s Table Bay: flat and not too big, and for an inmate like Nelson Mandela, a political prisoner there for eighteen long years, tantalizingly within view of shore.

We’re halfway around Africa now, down to the bottom, and island people and politics only get busier and more populated on the way back up. We’ll cover the other side of the continent in a future column.