by Marie Snyder

I recently listened to a podcast of Dr. Louis Cozolino, a neuroscientist and psychoanalyst, discussing what he would teach if he were training psychotherapists. The first year would be phenomenology: the power of Carl Rogers’ perspective to train how to develop an alliance through reflective listening while keeping countertransference out of the session. The second year would be physiology: developmental neuroscience and the evolutionary history of brains and bodies. The third year might be called intersectionality: the interpenetration of the spectrum of options that affect clients – brain, mind, family, culture – and a reaction against therapy as a mere opiate to calm the oppressed and exploited. The final year would be on narratives and stories that we live by and on that half second that it takes our brain to construct our experience of the present and feed it back to us.

Cozolino insists that it’s not enough to just sit and listen to people vent. After developing a non-judgmental alliance with the client, therapists need to be “amygdala whisperers,” to be able to down modulate amygdala activation to stop any inhibitory effect on the parietal system that enables problem solving. In other words, they need to soothe anxieties while arousing enough interest for clients to be able to learn new information. Then it’s time to challenge the client’s old system of thinking, slowly and delicately, a little at a time, to help them expand previous conceptualizations of themselves and the world. There’s a necessary plan and a strategy to the sessions.

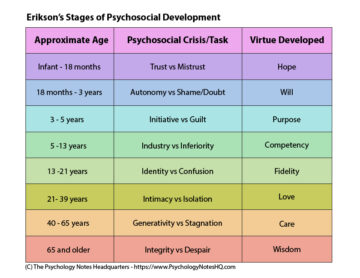

By contrast, in my MA psychotherapy program, we’re currently learning Piaget and Erikson’s stages of development that many of us first encountered in high school classes. There’s little to no encouragement to look at these older theories with a critical eye, and we’re required to identify stages without a clear idea of how that knowledge might practically help clients. I’m doing well in the class despite the reality that I don’t understand how acknowledging that a client is in the “identity vs role confusion” stage can provoke a useful change in the client’s perceptions.

So I read Erikson’s book from 1950, Childhood and Society, specifically looking at his notion of identity formation. There’s a surprising amount on Hitler, which has been left out of our lessons, how he used adolescent imagery to gain dominance, and I wonder if that might have provoked Erikson to promote a need to further our industrialization through our career-focused youth. Overall, I have some concerns with the linearity of his stages, with a career as the primary signifier of identity formation, and with what’s left out of his discussions of identity.

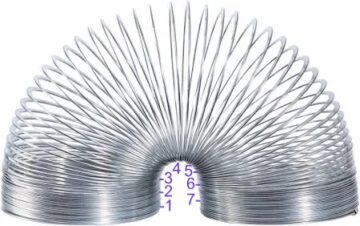

Erik Erikson significantly expanded Freud’s stages of development to acknowledge that we continue to change throughout the lifecycle, well beyond Freud’s endpoint of 18 years old. However, I generally disagree with the discontinuous idea of change through specific linear stages, in which, for instance, unresolved trust issues might make us fixate or stagnate at a specific age. Having experienced times of profound confidence and connection followed by times of abject alienation and back again, I propose a slinky theory instead. One moment of broken trust in infancy, for instance, can resolve, but then a second moment of broken trust as a toddler piggybacks on that moment, and then resolves again, over and over throughout our lives. We sometimes accept that nobody can be trusted, then our faith in humanity gets magically restored. Those difficult moments adhere together over time when we’re at a low point. We might aspire to have a life in which we just gain and gain on a continuous upward trajectory, but that doesn’t appear to be anything close to reality. The best childhood can only protect us so much from the negative effects of a devious interaction in our adult lives.

Snyder’s Slinky Theory Illustrated: Numbers indicate a few significantly troubling moments. 1. Mom didn’t come when we cried; 2. We couldn’t find dad at the park; 3. Friends took off on us; 4. We got stood up on a date; 5. Our partner had an affair; 6. Our kid stole from us, 7. We didn’t get that raise the boss promised, etc. The rest of time is recovery from these transgressions. There’s different points on the slinky for autonomy, initiative, and so forth, as it bends in all directions. Sometimes the events seem disparate and unconnected, but during a new experience of mistrust, they can be experienced as continuous and all encompassing as if these things always happen to us as our memory links them together.

We don’t ever fully learn that “people can be trusted”, because some of them can’t.

Erikson’s intimacy vs role confusion stage generally starts at puberty, but can last to 18 or 21. While Freud’s adolescent stage focuses almost exclusively on sexual awakening (see Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality, written in 1905), Erikson has a very different view of teenagers as far less interested in “embracing,” and I wonder how much of that is just wishful thinking as his own children fell in that age range at the time of his writing.

“The sense of ego identity, then, is the accrued confidence that the inner sameness and continuity are matched by the sameness and continuity of one’s meaning for others, as evidenced in the tangible promise of a ‘career.’ The danger of this stage is role diffusion. Where this is based on a strong previous doubt as to one’s sexual identity, delinquent and outright psychotic incidents are not uncommon. If diagnosed and treated correctly, these incidents do not have the same fatal significance which they have at other ages. It is primarily the inability to settle on an occupational identity which disturbs young people. To keep themselves together they temporarily overidentify, to the point of apparent complete loss of identity, with the heroes of cliques and crowds. . . . To a considerable extent adolescent love is an attempt to arrive at a definition of one’s identity by projecting one’s diffused ego images on one another and by seeing them thus reflected and gradually clarified. This is why many a youth would rather converse, and settle matters of mutual identification, than embrace” (228).

Identifying with cliques and crowds? That hasn’t changed much except to trickle further into adulthood.

However, concern with sameness and continuity could reflect the post war conformity sought after in a quest for stability and normalcy. More importantly, using the theory today to better understand clients ignores the dramatic shift in the job market. Only 6% of students went to college at the time (Erikson hadn’t), so landing a career to carry you clear to retirement right out of high school was much more of a possibility. Many teens today expect to have a variety of completely different types of jobs over the next forty years, so an occupation-derived identity falls apart.

Erikson, raised in the Jewish faith, converted to Christianity when he married in 1930, and then left Vienna for America in 1933 where he changed his name from Homburger. I would think identity would provoke far greater issues for him than merely occupational. Alternatively, perhaps it’s the case that his career trajectory was the most stable part of who he was, however that stability didn’t come until his thirties.

If identity were tied primarily to occupation, then it seems that sets people up for despair at retirement. Who are we if not our jobs?

Just before Erikson made these determinations about the stages, Sartre wrote at greater depth about identity. What Erikson discusses as identity, the types of things we might put on a résumé for instance, Sartre took for merely our facticity. To avoid all his hyphenated terms, it’s the facts about us that can constrain us from becoming. The other vital aspect of identity is transcendence, the potential to stretch beyond that list. Without that, we’re stuck stagnating in our current position without the possibility of future change. We operate from a position of inauthenticity when we think of ourselves as just one or another instead of always both. In psychotherapy, this understanding can help to recognize that we are much more than just our capabilities or talents.

Furthermore, we can look to older writing to find the notion of identity as a collection of memories ,

“Because we can reconstitute memories and this affects neural pathways by reinforcing or abandoning them, we can change our identity by changing our stories of ourselves.”

We can reframe the past to better understand ourselves in the present. And even further back we find writing suggesting that once we find our identity, the next task isn’t intimacy, as Erikson would have it, but dissolving identity for some oneness with the universe stuff! Another way to look at identity is not as something we form ourselves in a cognitive process, but something we recognize within us – something we uncover by removing the external pressures and layers covering all we currently value.

We develop an identity first by comparing and contrasting ourselves to others. But later the task becomes to separate the self from external ideas of how we should be and from decisions other people have made about us. Pronouncements made by others are free to be rejected or accepted, but it takes a conscious effort to question and consider if they’re on to something or mistaken. Otherwise we might form a shell around us that feels protective but becomes difficult to escape. Sartre complained about the power others have to stamp an impression on us despite what we know to be true about ourselves, concerned that in death we can no longer revise their errors.

Or as Jimmy Carr said,

“I think your identity is about more than just a few facts, it’s more than your behaviour. It’s about your core beliefs and values. And those are things that change over time. . . . I know who I am and I also know how I’m perceived. I think you need both.”

Attaching identity to any one aspect of the self will necessarily miss the vastness of our potential. We pretty quickly object to people reducing us to one aspect, but we too willingly do it to ourselves, often around our career or another role in our lives. Occupation is an external layer of skills and knowledge; it barely touches our core self.

Why does it matter?

We have an innate desire to live with a sense of being true to ourselves, living up to our own ideals with evidence that we’re being the kind of person we want to be. Otherwise we aim towards merely having what we want to have. We need to develop a unity of self so who we think we are aligns with our thoughts and actions, so our nature and our choices are congruent instead of being at odds. It just doesn’t feel right when it doesn’t all click.

A career can be a stand in for identity until we delve deeper, but as long as that works, it keeps us from looking further. In responding to external ideas of who we should be, we become estranged from ourselves. Our lives become little more than necessary fictions.