by Katalin Balog

Not so long ago, people had a very different concept of the mind and human nature. Our European heritage is a vision of the body as our mortal coil which we feel and command with our soul. The soul was thought to be immortal and exempt from the laws of nature so that our actions are not determined by anything outside of the boundaries of the soul. Souls of all sorts, of angels and spirits in addition to humans, permeated the universe. The universe was an ordered cosmos with human beings at the center of it with a very special role to play in it. It was commonly held that only the soul can truly exhibit creativity and intelligence which no mere mechanism could replicate. Dreams and visions were considered important messengers. All this is quite intuitive; and its remnants are probably deeply ingrained in the everyday manner in which we still think about ourselves. Descartes – who was also one of the founders of modern science – gave voice to many of these views in his philosophy and his influence on the field remains to this day.

During the last three hundred years, and especially in the 20th century, science has ushered in monumental changes in how we think about ourselves. It has become common knowledge that the mind and the brain are tied together in a systematic way. But what proved most consequential is the tremendous progress of physics, and in particular the idea, generally endorsed by scientists and philosophers, that every physical event can be fully explained in terms of prior physical causes. Since physical events include the movements of our bodies through space, it follows that our actions have purely physical causes. Since this leaves no room for the independent causal agency of the soul, belief in an immaterial, immortal soul not determined by physical reality has steadily declined. Materialism – or, as it has recently been dubbed, physicalism – the view that everything in the universe, including minds, is fundamentally physical, is ascendent. According to physicalism, mental processes – like feeling hungry or believing that most kangaroos are left-handed – happen in virtue of complicated physical processes in the brain. The recent rise of artificial intelligence is calling into question the uniqueness of human creativity, the very idea of distinctly human activities such as storytelling, poetry, art, music. Some predict that artificial intelligence, even perhaps soon, will be able to replicate every aspect of our humanity, except, arguably though controversially, conscious experience. There is not much about the premodern conception that has survived these changes, except the view that we are conscious beings, i.e., that there is, in Thomas Nagel’s expression, something it is like to be us. There is something it is like to hear the waves lapping against the shore or seeing water shimmering in a glass. Being a human being who perceives the world, and who thinks and feels, comes with a phenomenology of which we can be directly aware. Read more »

Michael Wang. Holoflora, 2024

Michael Wang. Holoflora, 2024 In the game of chess, some of the greats will concede their most valuable pieces for a superior position on the board. In a 1994 game against the grandmaster Vladimir Kramnik, Gary Kasparov sacrificed his queen early in the game with a move that made no sense to a middling chess player like me. But a few moves later Kasparov won control of the center board and marched his pieces into an unstoppable array. Despite some desperate work to evade Kasparov’s scheme, Kramnik’s king was isolated and then trapped into checkmate by a rook and a knight.

In the game of chess, some of the greats will concede their most valuable pieces for a superior position on the board. In a 1994 game against the grandmaster Vladimir Kramnik, Gary Kasparov sacrificed his queen early in the game with a move that made no sense to a middling chess player like me. But a few moves later Kasparov won control of the center board and marched his pieces into an unstoppable array. Despite some desperate work to evade Kasparov’s scheme, Kramnik’s king was isolated and then trapped into checkmate by a rook and a knight.

In Discourse on the Method, philosopher René Descartes reflects on the nature of mind. He identifies what he takes to be a unique feature of human beings— in each case, the presence of a rational soul in union with a material body. In particular, he points to the human ability to think—a characteristic that sets the species apart from mere “automata, or moving machines fabricated by human industry.” Machines, he argues, can execute tasks with precision, but their motions do not come about as a result of intellect. Nearly four-hundred years before the rise of large language computational models, Descartes raised the question of how we should think of the distinction between human thought and behavior performed by machines. This is a question that continues to perplex people today, and as a species we rarely employ consistent standards when thinking about it.

In Discourse on the Method, philosopher René Descartes reflects on the nature of mind. He identifies what he takes to be a unique feature of human beings— in each case, the presence of a rational soul in union with a material body. In particular, he points to the human ability to think—a characteristic that sets the species apart from mere “automata, or moving machines fabricated by human industry.” Machines, he argues, can execute tasks with precision, but their motions do not come about as a result of intellect. Nearly four-hundred years before the rise of large language computational models, Descartes raised the question of how we should think of the distinction between human thought and behavior performed by machines. This is a question that continues to perplex people today, and as a species we rarely employ consistent standards when thinking about it. The human tendency to anthropomorphize AI may seem innocuous, but it has serious consequences for users and for society more generally. Many people are responding to the

The human tendency to anthropomorphize AI may seem innocuous, but it has serious consequences for users and for society more generally. Many people are responding to the

I’ve been surfing for about three years.

I’ve been surfing for about three years.  Sughra Raza. After The Rain. Vermont, July 2024.

Sughra Raza. After The Rain. Vermont, July 2024.

Karl Ove Knausgaard went around for many years claiming that he was sick of fiction and couldn’t stand the idea of made-up characters and invented plots. People understood this to be an explanation of why he had decided to write six long books about his own life. There was some truth in this, but the simple contrast between fiction and reality was complicated by the fact that Knausgaard referred to his autobiographical books as novels. Were they real? Was the Karl Ove of the story the same as the author? It seemed like it, but then why call them novels? The problem lay with the word “fiction.” Like a German philosopher, Knausgaard had his own definitions for words that we thought we all agreed on.

Karl Ove Knausgaard went around for many years claiming that he was sick of fiction and couldn’t stand the idea of made-up characters and invented plots. People understood this to be an explanation of why he had decided to write six long books about his own life. There was some truth in this, but the simple contrast between fiction and reality was complicated by the fact that Knausgaard referred to his autobiographical books as novels. Were they real? Was the Karl Ove of the story the same as the author? It seemed like it, but then why call them novels? The problem lay with the word “fiction.” Like a German philosopher, Knausgaard had his own definitions for words that we thought we all agreed on.

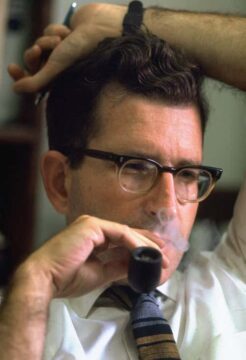

Noam Chomsky was rumoured to have left us almost a month ago, but he always

Noam Chomsky was rumoured to have left us almost a month ago, but he always