by Marie Snyder

I started reading about burnout when I walked away from teaching earlier than expected. Suddenly, I couldn’t bring myself to open that door after over thirty years of bounding to work. A series of events wiped away any sense of agency, fairness, or shared values. Their wellness lunch-and-learns didn’t help me, and I soon discovered I’m not alone.

I started reading about burnout when I walked away from teaching earlier than expected. Suddenly, I couldn’t bring myself to open that door after over thirty years of bounding to work. A series of events wiped away any sense of agency, fairness, or shared values. Their wellness lunch-and-learns didn’t help me, and I soon discovered I’m not alone.

An article published in JAMA last June looked at rising rates of burnout in healthcare, where 40% of physicians surveyed intended to leave their practice. They suggest, “To prevent a health care worker exodus, experts argue that the emphasis needs to shift from individual resilience to broader system-level improvements.” They are looking for standardized methods to affect organizational management with “evidence-based interventions.”

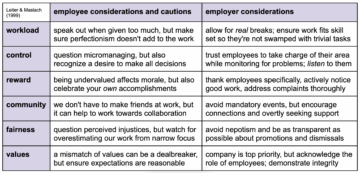

Over 25 years ago, Michael Leiter and Christina Maslach came to the same conclusion. They identified six areas of worklife affecting burnout and created a specific assessment for educators. They determined the cause to be a “mismatch” between employee expectations and employer behaviours leading workers to be closer to the bleak end of a continuum from burned out to engaged. They suggest that “the task for organizations and individuals is to achieve a resolution.” This is not just a matter of throwing wellness initiatives or resilience-speak into the mix, but addressing any reasonable expectations of employees with appropriate employer interventions in all six interrelating areas.

Feels vindicating, right?!

One problem with this solution and possibly a reason why it’s not widespread, however, is that it’s often the employees that hold the highest standards and care for the workplace who are the most affected by burnout, and they might make up a small minority of workers. People who show up to learn the right buzzwords and put in the least effort required to hit their hours without concern for the process and product of the company can feel unscathed, and those employees can make up enough of the workforce to provoke organizations to continue the micromanaging and questionable reward schemes for the many. Read more »

Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations begins with this claim:

Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations begins with this claim: