by Mark R. DeLong

Human beings thought with their hands. It was their hands that were the answer of curiosity, that felt and pinched and turned and lifted and hefted. There were animals that had brains of respectable size, but they had no hands and that made all the difference. (Isaac Asimov, Foundation’s Edge)

Eugene Russell, a piano tuner interviewed by Studs Terkel in Working, said with satisfaction that the computer wouldn’t be replacing him anytime soon, even though he mentioned electronic devices—“an assist,” he said, that helps tuners. Eugene’s wife Natalie felt otherwise, saying at one point in their conversation, “It’s an electronic thing now. Anyone in the world can tune a piano with it. You can actually have a tin ear like a night club boss.”

Eugene Russell, a piano tuner interviewed by Studs Terkel in Working, said with satisfaction that the computer wouldn’t be replacing him anytime soon, even though he mentioned electronic devices—“an assist,” he said, that helps tuners. Eugene’s wife Natalie felt otherwise, saying at one point in their conversation, “It’s an electronic thing now. Anyone in the world can tune a piano with it. You can actually have a tin ear like a night club boss.”

Eugene mixed elements of beauty and delight with the technical complexity of piano tuning, recalling how he would “hear great big fat augmented chords that you don’t hear in music today” and that he would come home and say, “I just heard a diminished chord today!” Once he was tuning a piano in a hotel ballroom during “a symposium of computer manufacturers. One of these men came up and tapped me on the shoulder. ‘Someday we’re going to get your job.’ I laughed. By the time you isolate an infinite number of harmonics, you’re going to use up a couple billion dollars worth of equipment to get down to the basic fundamental that I work with my ear.”

The piano tuner feels and practices the tune, which is hardly reducible to formulae, perhaps because it is one of those things in life that’s approximated, but not unambiguously achieved. At best, tuning a piano is a compromise: “The nature of equal temperament makes it impossible to really put a piano in tune,” Eugene explained. “The system is out of tune with itself. But it’s so close to in tune that it’s compatible.” Read more »

Obviously, “Donald Trump” here is a placeholder for any political figure who one wishes to insult. But the joke raises an interesting question. What kind of work , if any, is shameful? And it also suggests a way of posing the question: viz. what kind of work might a child be ashamed to admit that their parents performed? This is an interesting dinner table conversation topic.

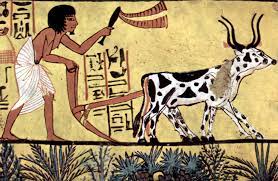

Obviously, “Donald Trump” here is a placeholder for any political figure who one wishes to insult. But the joke raises an interesting question. What kind of work , if any, is shameful? And it also suggests a way of posing the question: viz. what kind of work might a child be ashamed to admit that their parents performed? This is an interesting dinner table conversation topic. If, for a long time now, you’ve been getting up early in the morning, setting off to school or your workplace, getting there at the required time, spending the day performing your assigned tasks (with a few scheduled breaks), going home at the pre-ordained time, spending a few hours doing other things before bedtime, then getting up the next morning to go through the same routine, and doing this most days of the week, most weeks of the year, most years of your life, then the working life in its modern form is likely to seem quite natural. But a little knowledge of history or anthropology suffices to prove that it ain’t necessarily so.

If, for a long time now, you’ve been getting up early in the morning, setting off to school or your workplace, getting there at the required time, spending the day performing your assigned tasks (with a few scheduled breaks), going home at the pre-ordained time, spending a few hours doing other things before bedtime, then getting up the next morning to go through the same routine, and doing this most days of the week, most weeks of the year, most years of your life, then the working life in its modern form is likely to seem quite natural. But a little knowledge of history or anthropology suffices to prove that it ain’t necessarily so. The coronavirus pandemic has caused a great of suffering and has disrupted millions of lives. Few people welcome this kind of disruption; but as many have already observed, it can be the occasion for reflection, particularly on aspects of our lives that are called into question, appear in a new light, or that we were taking for granted but whose absence now makes us realize were very precious. For many people, work, which is so central to their lives, is one of the things that has been especially disrupted. The pandemic has affected how they do their job, how they experience it, or whether they even still have a job at all. For those who are working from home rather than commuting to a workplace shared with co-workers, the new situation is likely to bring a new awareness of the relation between work and time. So let us reflect on this.

The coronavirus pandemic has caused a great of suffering and has disrupted millions of lives. Few people welcome this kind of disruption; but as many have already observed, it can be the occasion for reflection, particularly on aspects of our lives that are called into question, appear in a new light, or that we were taking for granted but whose absence now makes us realize were very precious. For many people, work, which is so central to their lives, is one of the things that has been especially disrupted. The pandemic has affected how they do their job, how they experience it, or whether they even still have a job at all. For those who are working from home rather than commuting to a workplace shared with co-workers, the new situation is likely to bring a new awareness of the relation between work and time. So let us reflect on this.