by Marie Snyder

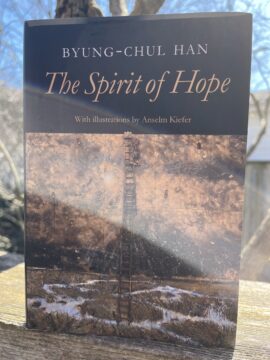

Byung-Chul Han’s The Spirit of Hope is a beautiful book, the kind you want to treat with care and won’t dare dog-ear a page. Anselm Kiefer’s illustrations throughout provide a place for contemplative moments between ideas. It’s more immediately accessible than The Burnout Society, which took me weeks to wrap my head around, yet no less profound.

A REVOLUTIONARY POLITICS OF HOPE

We like a secure illusion of control over the world, yet that hasn’t gotten us much further along. We recognize something’s missing. Han writes, “Amid problem-solving and crisis management, life withers. It becomes survival. … It is hope that opens up a meaningful horizon” (2).

Han explains how a lack of hope furthers the current neoliberal capitalist trajectory:

“Fear and resentment drive people into the arms of the right-wing populists. They breed hate. Solidarity, friendliness and empathy are eroded. … Democracy flourishes only in an atmosphere of reconciliation and dialogue. … Hope provides meaning and orientation. Fear, by contrast, stops us in our tracks. … Hope is eloquent. It narrates. Fear, by contrast, is incapable of speech, incapable of narration” (2-3).

Climate activist Roger Hallam recently wrote that the human race is likely going extinct this century, yet he demonstrates his hope in the very action of continuing to write our way through and by suggesting public alternatives to political capture. When we’re no longer open to seeing possibilities, we get held fast by fear, but it appears to be a feature of the system, not a bug.

“The current omnipresent fear is not really the effect of an ongoing catastrophe. … The neoliberal regime is a regime of fear. It isolates people by making them entrepreneurs of themselves. … Our relation to ourselves is also increasingly dominated by fear: fear of failing; fear of not living up to one’s own expectations; fear of not keeping up with the rest, or fear of being left behind. The ubiquity of fear is good for productivity. … To be free means to be free of compulsion. In the neo-liberal regime, however, freedom produces compulsion. These forms of compulsion are not external; they come from within. The compulsion to perform and the compulsion to optimize oneself are compulsions of freedom. Freedom and compulsion become one. … We optimize ourselves, exploit ourselves, to the bitter end, while harbouring the illusion that we are realizing ourselves. These inner compulsions intensify fear, and ultimately make us depressive. Self-creation is a form of self-exploitation that serves the purpose of increasing productivity” (9-10).

This brings to mind the many life hacks promoted to help self-automate our lives by creating habits to try to help us blow through chores and work without noticing it, as if to better sleepwalk through it all in a psychological version of Severance. As long as we’re optimizing ourselves, we’re not being; we’re merely objects that can work more efficiently, which further prevents our connection with others. Social media also paradoxically erodes social coherence, but “Hope is a counter-figure, even a counter-mood, to fear: rather than isolating us, it unites and forms communities” (10-11). Read more »

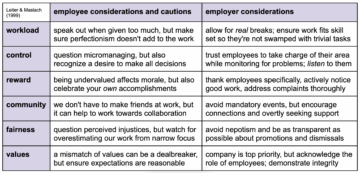

I started reading about burnout when I walked away from teaching earlier than expected. Suddenly, I couldn’t bring myself to open that door after over thirty years of bounding to work. A series of events wiped away any sense of agency, fairness, or shared values. Their wellness lunch-and-learns didn’t help me, and I soon discovered I’m not alone.

I started reading about burnout when I walked away from teaching earlier than expected. Suddenly, I couldn’t bring myself to open that door after over thirty years of bounding to work. A series of events wiped away any sense of agency, fairness, or shared values. Their wellness lunch-and-learns didn’t help me, and I soon discovered I’m not alone.