by Michael Liss

April 1, 1865. For the South, the end is nearing. It was already obvious on March 4, when Abraham Lincoln delivered his magnificent Second Inaugural Address. Four weeks later, it is more obvious. For all the bravery of the Confederacy’s men and all the talent of its military leadership, its resources are almost gone. A great test, possibly a decisive one, awaits it at the Battle of Five Forks, Virginia. For more than nine months, Union and Confederate forces have been punching and counterpunching around the besieged town of Petersburg. The stalemate has cost more than 70,000 casualties, expended stupendous amounts of arms and supplies, and caused great civilian suffering, but, to Grant’s endless frustration, success has eluded his grasp. This time would be different. At Five Forks, one of Grant’s most able generals, Philip Sheridan, defeats a portion of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia under General George Pickett. The price, for an army with nothing more to give, is nearly fatal—1,000 casualties, 4,000 captured or surrendered, and, even more crucially, the loss of access to the South Side Railroad, a major transit point for men and material.

April 2, 1865. The strategic cost of Five Forks is driven home. Robert E. Lee abandons both Petersburg and Richmond. Jefferson Davis and his government flee, burning what documents and supplies as they can. Lee moves his army West toward North Carolina, hoping to escape Grant and join up with Confederate forces under General Joseph Johnston. The loss of Richmond is much more than symbolic—it had also been a critical manufacturing hub, and it contained one of the South’s largest hospitals—but Lee realized Richmond was a necessity that had become a luxury. To stave off a larger defeat, he had to save his army. The last hope for the Confederacy depended on it. If Lee and his men could stay in the field, move rapidly, inflict damage, prolong the conflict, then they still had a chance. Lee thought it possible, but he was running out of everything—clothes, food, ammunition, and even men. It wasn’t just casualties that caused his army to shrink. Estimates are that at least 100 Confederate soldiers a day were simply deserting, driven by fear, hunger, and plaintive words from home.

April 3, 1865. Richmond and Petersburg fall, as United States troops occupy both. A day later, the fantastical happens. Lincoln, accompanied by son Tad and the most appallingly small security contingent, visit Richmond. The risk is stupendous—the city is burning, the harbor is filled with torpedoes, and potential assailants lurk literally anywhere. But the scene is incredible. It’s Jubilee for the slaves, some of whom fall to their feet when they recognize the tall man in the top hat. Now freed men, they gather, march, shout, and sing hymns. To tremendous cheers, Lincoln walks to the “Confederate White House,” climbs the stairs, and plunks himself down in a comfortable chair in what had been Jefferson Davis’s study. Read more »

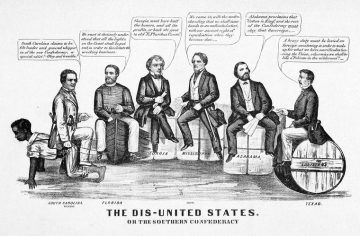

Did we need to have a Civil War? Couldn’t the two sides, geographically defined as they were, simply part before the shooting started? Did Lincoln intentionally choose war for any one of a variety of unworthy reasons that stopped short of necessity, including even something so mundane as a fear of losing face? Or was he faced with an intractable situation for which there was no simple, satisfactory answer—a type of political Trolley Problem?

Did we need to have a Civil War? Couldn’t the two sides, geographically defined as they were, simply part before the shooting started? Did Lincoln intentionally choose war for any one of a variety of unworthy reasons that stopped short of necessity, including even something so mundane as a fear of losing face? Or was he faced with an intractable situation for which there was no simple, satisfactory answer—a type of political Trolley Problem?

November 6, 1860. Perhaps the worst day in James Buchanan’s political life. His fears, his sympathies and antipathies, the judgment of the public upon an entire career, all converge into a horrible realty. Abraham Lincoln, of the “Black Republican Party,” has been elected President of the United States.

November 6, 1860. Perhaps the worst day in James Buchanan’s political life. His fears, his sympathies and antipathies, the judgment of the public upon an entire career, all converge into a horrible realty. Abraham Lincoln, of the “Black Republican Party,” has been elected President of the United States.  He is an enigma. He sits up there in his marble chair, set in a Greek temple, literally larger than life, and he defies us to understand him.

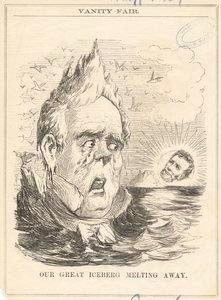

He is an enigma. He sits up there in his marble chair, set in a Greek temple, literally larger than life, and he defies us to understand him. By the time Sherman’s armies had scorched and bow-tied their way to the sea, by the time Halleck had followed Grant’s orders to “eat out Virginia clean and clear as far as they go, so that crows flying over it for the balance of the season will have to carry their own provender with them,” and by the time Winfield Scott’s Anaconda Plan was finished squeezing every drop of life out of the Confederacy, there had to be those who wondered what possible logic would lead intelligent men like Jefferson Davis to make such a catastrophic choice.

By the time Sherman’s armies had scorched and bow-tied their way to the sea, by the time Halleck had followed Grant’s orders to “eat out Virginia clean and clear as far as they go, so that crows flying over it for the balance of the season will have to carry their own provender with them,” and by the time Winfield Scott’s Anaconda Plan was finished squeezing every drop of life out of the Confederacy, there had to be those who wondered what possible logic would lead intelligent men like Jefferson Davis to make such a catastrophic choice.