by Chris Horner

Things we don’t want to know that we know.

Donald Rumsfeld’s famous distinctions between knowledge and ignorance:

[T]here are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don’t know we don’t know. [1]

It’s been suggested that we should add to that list another kind of ‘known’: unknown knowns. [2] these would be the kinds of things we actually do know, but somehow remain unaware that we know. The classic example would be repression: a painful memory is repressed from our consciousness, but continues to be present in the unconscious – where it may return to trouble us via dreams, symptoms and parapraxes (so-called ‘Freudian slips’). So we (unconsciously) know something, but do not (consciously) know that we know it.

But there is another variety of knowing that isn’t ‘unknown’, but inhabits a twilight zone between knowing and acknowledging: Fetishistic disavowal. This is where we do know something, but act on the basis that ‘I know this perfectly well, but nevertheless….’. To disavow something is to deny it; to fetishise something is to invest it with special powers. One knows that something is the case, but denies it to oneself. This is obviously paradoxical, for how can I know X is the case but at the same time deny it? How can I act a belief that I consciously deny, or deny something that my actions show that I believe? This is where the unconscious, fantasy, and the fetish, enter in. Read more »

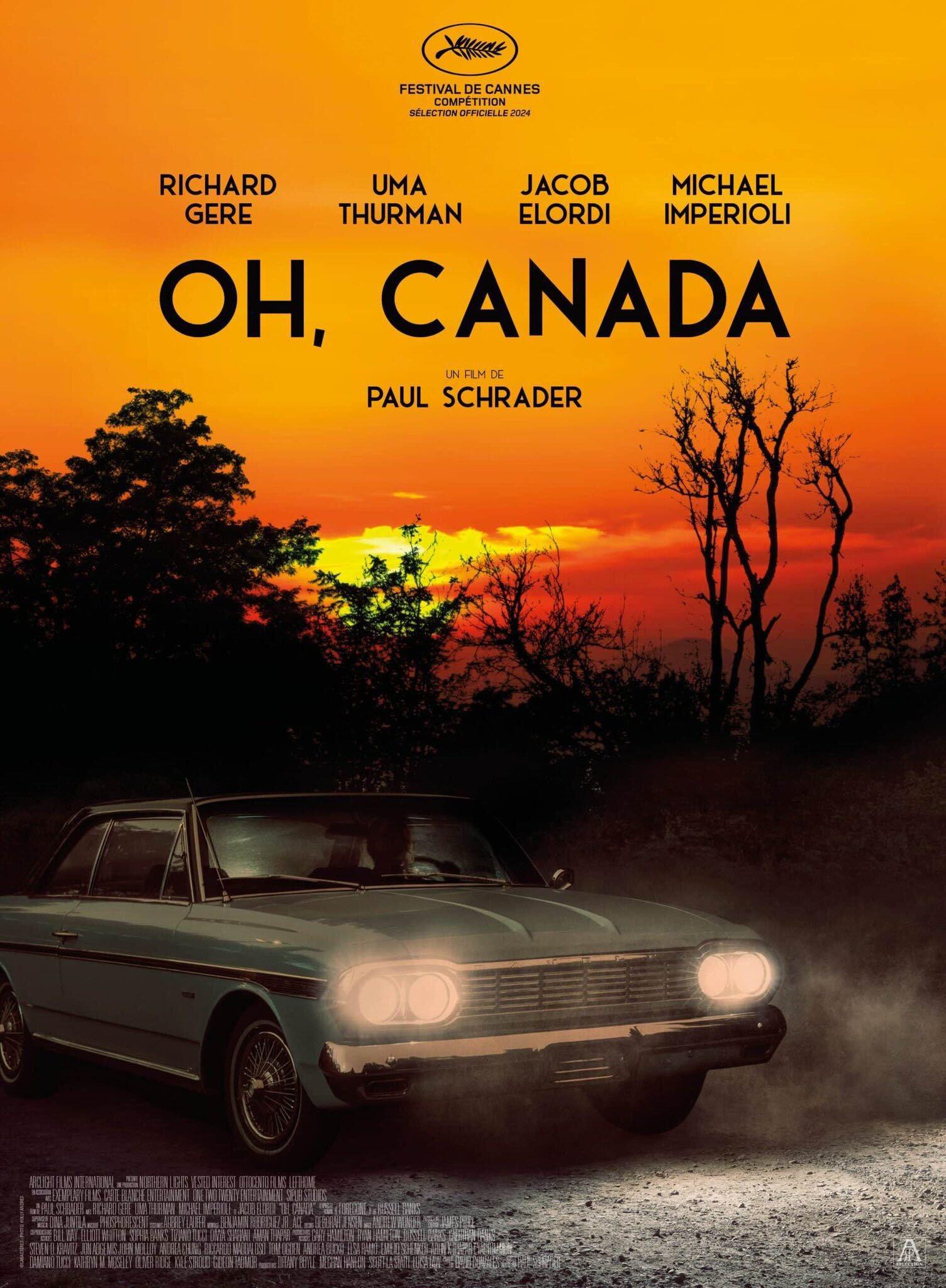

I was in Toronto the other day to see Paul Schrader’s newest film, Oh, Canada, which was screening at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF). This was my first time seeing a movie at a festival, and the experience was quite different from seeing a movie at a cinema: we had to line up in advance, the location was not a cinema but a theatre (in this case, the Princess of Wales Theater, a beautiful venue with orchestra seating, a balcony, and plush red carpeting), and there was a buzz in the air, as everyone in attendance had made a special effort to see a movie they wouldn’t be able to see elsewhere. As I stood in line with the other ticket holders, I noticed that there was a clear difference between the type of person in my line, for those with advance tickets, and the rush line, for those without tickets and who would be allowed in only in the case of no shows: in my line, the attendees were older, often in couples, and had the air of Money and Culture about them; in the rush line, the hopeful attendees were younger, often male, and solitary. In other words, those in the rush line, the ones who couldn’t get their shit together to buy a ticket in time, could have been typical Schrader protagonists: a man in a room, trying, yet frequently failing, to live a meaningful life, to keep it together, to be the type of person who buys a ticket in advance, and invites his wife, too. Yet there I was, in the advance ticket line: a man, relatively young, and someone who spends a good deal of time by himself. I’d invited my partner of 10 years, but she didn’t come because she doesn’t like Paul Schrader films, and who can blame her? They’re not for everyone. Perhaps my presence in the advance ticket line, but my understanding of and identification with those in the other line, helps explain my deep attraction to Schrader’s films: I know his characters, and in the right circumstances, I could become one of his characters.

I was in Toronto the other day to see Paul Schrader’s newest film, Oh, Canada, which was screening at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF). This was my first time seeing a movie at a festival, and the experience was quite different from seeing a movie at a cinema: we had to line up in advance, the location was not a cinema but a theatre (in this case, the Princess of Wales Theater, a beautiful venue with orchestra seating, a balcony, and plush red carpeting), and there was a buzz in the air, as everyone in attendance had made a special effort to see a movie they wouldn’t be able to see elsewhere. As I stood in line with the other ticket holders, I noticed that there was a clear difference between the type of person in my line, for those with advance tickets, and the rush line, for those without tickets and who would be allowed in only in the case of no shows: in my line, the attendees were older, often in couples, and had the air of Money and Culture about them; in the rush line, the hopeful attendees were younger, often male, and solitary. In other words, those in the rush line, the ones who couldn’t get their shit together to buy a ticket in time, could have been typical Schrader protagonists: a man in a room, trying, yet frequently failing, to live a meaningful life, to keep it together, to be the type of person who buys a ticket in advance, and invites his wife, too. Yet there I was, in the advance ticket line: a man, relatively young, and someone who spends a good deal of time by himself. I’d invited my partner of 10 years, but she didn’t come because she doesn’t like Paul Schrader films, and who can blame her? They’re not for everyone. Perhaps my presence in the advance ticket line, but my understanding of and identification with those in the other line, helps explain my deep attraction to Schrader’s films: I know his characters, and in the right circumstances, I could become one of his characters.

In 1977, I was a student at the University of Pennsylvania, majoring in French Literature. I was 19 years old and pregnant with my first child. I would dress in a long shapeless plaid green and black dress, tie my hair with an off-white headscarf, and wear Dr. Scholl’s slide sandals trying very hard to blend in and look cool and hippyish, but that look wasn’t really working well for me. The scarf at times became a long neck shawl and the ‘cool and I don’t care’ 70’s look became more of a loose colorless dress on top of my plaid dress, giving me the appearance of a field-working peasant. My sandals added absolutely nothing, except making me trip on the sidewalks.

In 1977, I was a student at the University of Pennsylvania, majoring in French Literature. I was 19 years old and pregnant with my first child. I would dress in a long shapeless plaid green and black dress, tie my hair with an off-white headscarf, and wear Dr. Scholl’s slide sandals trying very hard to blend in and look cool and hippyish, but that look wasn’t really working well for me. The scarf at times became a long neck shawl and the ‘cool and I don’t care’ 70’s look became more of a loose colorless dress on top of my plaid dress, giving me the appearance of a field-working peasant. My sandals added absolutely nothing, except making me trip on the sidewalks. The writer Tabish Khair was born in 1966 and educated in Bihar before moving first to Delhi and then Denmark. He is the author of various acclaimed books, including novels

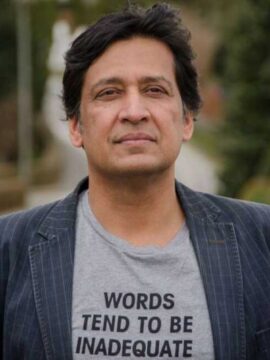

The writer Tabish Khair was born in 1966 and educated in Bihar before moving first to Delhi and then Denmark. He is the author of various acclaimed books, including novels

Sughra Raza. Rain. Hund Riverbank, Pakistan, November 2023.

Sughra Raza. Rain. Hund Riverbank, Pakistan, November 2023.