by John Allen Paulos

When studying a technical field there is a strong temptation, especially among those without a scientific background, to apply its findings in areas where they may not make sense or are merely metaphors. (“Merely” is perhaps unnecessarily dismissive since much of our understanding of these fields is metaphorical.) Quantum mechanics and Godel’s theorems are often used (or abused) in this way. Precipitous changes are deemed “quantum jumps” or unusual statements are proclaimed “undecidable.” Not even set theory is immune. I once heard a commentator refer to some curtailment of the first amendment as being inconsistent with the mathematical axiom of choice. Having mocked these pseudoscientific references, I nevertheless, and with a bit of trepidation, would like to briefly explore a metaphorical aspect of chaos theory.

Chaos theory, roughly speaking, studies complex systems of one sort or another whose state or condition changes or evolves over time and are hence termed dynamical systems. The underlying equations or laws describing them are deterministic, but they often give rise to systems very sensitive to initial conditions. (Tiny variations cascading into huge differences.) The systems are also nonlinear, which means that the effects of changes are not directly proportional to their causes. And, trumpets sound here, an astonishing property of nonlinear dynamical systems is that they can exhibit quite unpredictable behaviors that might appear might random, even though subject to deterministic laws.

What might such systems tell us not only about weather systems or economic systems, but also about our own inability to predict or make sense of things? An obstacle to predictability is the utter complexity of the associations and linkages in the world and ultimately in our brain. They can be chaotic in both the everyday sense and in the mathematical sense, the description of which I’ll spare you. Regarding the latter sense, the so-called Horseshoe procedure devised by topologist Steve Smale to illustrate the evolution of systems from regularity to mathematical chaos, is most suggestive. Such procedures or mappings are, in fact, a distinguishing feature of chaos.

To understand the procedure, imagine a cubical piece of white clay with a very thin layer of bright red dye running through the middle of it and forming a sort of red dye sandwich. Read more »

The world does not lend itself well to steady states. Rather, there is always a constant balancing act between opposing forces. We see this now play out forcefully in AI.

The world does not lend itself well to steady states. Rather, there is always a constant balancing act between opposing forces. We see this now play out forcefully in AI.

The sleet falls so incessantly this Sunday that the sky turned a dull gray and we don’t want to go anywhere, my child, his friend and me. We didn’t go to the theater or to the Brazilian Roda de Feijoada and we didn’t even bake cookies at the neighbors’ place, but instead are playing cars on the floor and cooking soup and painting the table blue when the news arrives.

The sleet falls so incessantly this Sunday that the sky turned a dull gray and we don’t want to go anywhere, my child, his friend and me. We didn’t go to the theater or to the Brazilian Roda de Feijoada and we didn’t even bake cookies at the neighbors’ place, but instead are playing cars on the floor and cooking soup and painting the table blue when the news arrives.

“You were present on the occasion of the destruction of these trinkets, and, indeed, are the more guilty of the two, in the eye of the law; for the law supposes that your wife acts under your direction.”

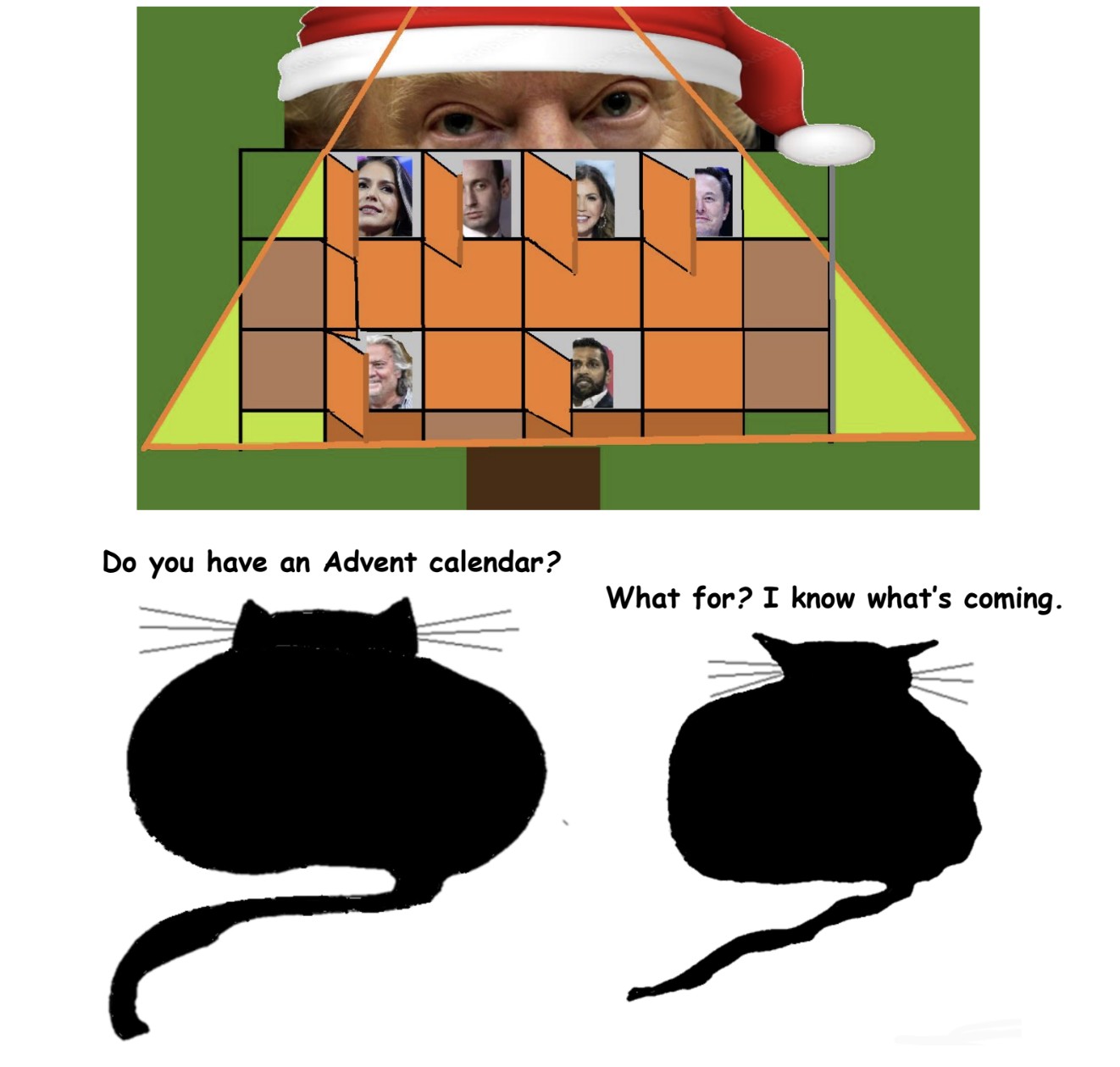

“You were present on the occasion of the destruction of these trinkets, and, indeed, are the more guilty of the two, in the eye of the law; for the law supposes that your wife acts under your direction.” I was recently subjected to an hour of the “All In” Podcast while on a long car ride. This podcast is not the sort I normally listen to. I prefer sports podcasts—primarily European soccer—and that’s about the extent of my consumption. I like my podcasts to be background noise and idle chatter, something to listen to while I do the dishes or sweep the floor, just something to fill the void of silence. On the way to work this morning I had sports talk radio on—the pre-podcast way to fill silence—and they were discussing the physical differences between two football wide receivers—Calvin Johnson and DK Metcalfe—before switching to two running backs—Derrick Henry and Mark Ingram.

I was recently subjected to an hour of the “All In” Podcast while on a long car ride. This podcast is not the sort I normally listen to. I prefer sports podcasts—primarily European soccer—and that’s about the extent of my consumption. I like my podcasts to be background noise and idle chatter, something to listen to while I do the dishes or sweep the floor, just something to fill the void of silence. On the way to work this morning I had sports talk radio on—the pre-podcast way to fill silence—and they were discussing the physical differences between two football wide receivers—Calvin Johnson and DK Metcalfe—before switching to two running backs—Derrick Henry and Mark Ingram. Sughra Raza. Being In the Airplane Movie. Dec 4, 2024.

Sughra Raza. Being In the Airplane Movie. Dec 4, 2024.

1.

1. 2.

2.