by Akim Reinhardt

There’s a lot going on right now. Lowlights include racism, misogyny, and transphobia; xenophobia amid undulating waves of global migrations; democratic state capture by right wing authoritarians; and secular state capture by fundamentalist Christian, Jewish, Muslim, and Hindu nationalists.

There’s a lot going on right now. Lowlights include racism, misogyny, and transphobia; xenophobia amid undulating waves of global migrations; democratic state capture by right wing authoritarians; and secular state capture by fundamentalist Christian, Jewish, Muslim, and Hindu nationalists.

Among the many factors causing and influencing these complex phenomena are: the rebound from Covid lockdowns and the years-long economic upheavals they wrought; brutal warfare in Europe, the Middle East, and Africa among other places; and intense weather-related fiascos stemming from the rise in global temperatures. But one I’d like to focus on is a growing sense of male insecurity.

The latest “crisis” in masculinity is not more important than other issues. However, I’m currently attuned to it for several reasons. One is that as I wade through late middle-age, I’m becoming ever more secure in (ie. relaxed about) my own masculinity, which in turn leads me to better notice gender insecurity in other men. Another is that I believe American male insecurity played a vital role in the recent election of Donald Trump and, as such, demands attention. Qualitative and quantitative data about Trump getting more votes than expected from young men with college education, from black men, and from brown men, signal something. And finally, as a historian, shit storms rising up from perceived crises in masculinity are not new to me.

In the United States, a broad crisis of white masculinity first emerged during the early 19th century. Then, as now, it was driven by economic changes and by challenges to established patriarchy, and it found expression in religion and politics. Read more »

There’s an old story, popularized by the mathematician Augustus De Morgan (1806-1871) in A Budget of Paradoxes, about a visit of Denis Diderot to the court of Catherine the Great. In the story, the Empress’s circle had heard enough of Diderot’s atheism, and came up with a plan to shut him up. De Morgan

There’s an old story, popularized by the mathematician Augustus De Morgan (1806-1871) in A Budget of Paradoxes, about a visit of Denis Diderot to the court of Catherine the Great. In the story, the Empress’s circle had heard enough of Diderot’s atheism, and came up with a plan to shut him up. De Morgan

Sughra Raza. Science Experiment as Painting. April, 2017.

Sughra Raza. Science Experiment as Painting. April, 2017.

My friend R is a man who takes his simple pleasures seriously, so I asked him to name one for me. Boathouses, he said, without hesitation.

My friend R is a man who takes his simple pleasures seriously, so I asked him to name one for me. Boathouses, he said, without hesitation.

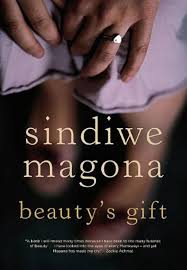

Early on, Magona presents readers of Beauty’s Gift with a startling image: the beautiful and ‘beloved’ Beauty laid to rest in an opulent casket, which is then fixed in the earth with cement to prevent theft. Her friends’ memories of Beauty’s charisma and kindness are concretized by the weight of her death from AIDS. From the outset, funerals emerge not merely as a plot point but a structuring device for understanding the social and political implications of the AIDS crisis in South Africa. After opening her novel with Beauty’s funeral, Magona continues with vignettes about various stages of illness, death, and grief. These include a wake, the mourning period, Beauty’s posthumous

Early on, Magona presents readers of Beauty’s Gift with a startling image: the beautiful and ‘beloved’ Beauty laid to rest in an opulent casket, which is then fixed in the earth with cement to prevent theft. Her friends’ memories of Beauty’s charisma and kindness are concretized by the weight of her death from AIDS. From the outset, funerals emerge not merely as a plot point but a structuring device for understanding the social and political implications of the AIDS crisis in South Africa. After opening her novel with Beauty’s funeral, Magona continues with vignettes about various stages of illness, death, and grief. These include a wake, the mourning period, Beauty’s posthumous

Humans are beings of staggering complexity. We don’t just consist of ourselves: billions of bacteria in our gut help with everything from digestion to immune response.

Humans are beings of staggering complexity. We don’t just consist of ourselves: billions of bacteria in our gut help with everything from digestion to immune response.