by Rafaël Newman

Saidiya Hartman made her second trip to Ghana in 1997. She had visited the country briefly the year before, as a tourist, but now, having recently completed a doctorate at Yale and published her first book, she was in Ghana as a Fulbright Scholar searching for historical evidence of local resistance to slave raids. She was also, as a Black American, in quest of a connection with her putative ancestral homeland, and hoping to flesh out her work, both scholarly and personal, in the archives, where she had had a fleeting glimpse of her heritage as the descendant of people kidnapped and indentured, as “chattel,” to slave-owners in the New World.

I chose Ghana because it possessed more dungeons, prisons, and slave pens than any other country in West Africa—tight dark cells buried underground, barred cavernous cells, narrow cylindrical cells, dank cells, makeshift cells. In the rush for gold and slaves that began at the end of the fifteenth century, the Portuguese, English, Dutch, French, Danes, Swedes, and Brandenburgers (Germans) built fifty permanent outposts, forts, and castles designed to ensure their place in the Africa trade. In these dungeons, storerooms, and holding cells, slaves were imprisoned until transported across the Atlantic.

Until it wrested its independence from the British in 1957 Ghana was known as Gold Coast, a name that commemorates the commodity that had first brought Europeans to the region in the 1400s, but which belies the more nefarious commerce that kept them there four centuries long. The country we now call Ghana, named by its first president, Kwame Nkrumah, for a revered but defunct medieval kingdom to its north, was until the 1800s the crossroads for several slave routes from the inland to the sea, and to passage, for those kidnapped, across the Atlantic to a life of servitude. Ghana’s coastline is studded with forts and castles—command centers and entrepôts for the trade in people enslaved from throughout west central Africa: effectively concentration camps—like a string of poisoned beads. Read more »

There’s an old story, popularized by the mathematician Augustus De Morgan (1806-1871) in A Budget of Paradoxes, about a visit of Denis Diderot to the court of Catherine the Great. In the story, the Empress’s circle had heard enough of Diderot’s atheism, and came up with a plan to shut him up. De Morgan

There’s an old story, popularized by the mathematician Augustus De Morgan (1806-1871) in A Budget of Paradoxes, about a visit of Denis Diderot to the court of Catherine the Great. In the story, the Empress’s circle had heard enough of Diderot’s atheism, and came up with a plan to shut him up. De Morgan

Sughra Raza. Science Experiment as Painting. April, 2017.

Sughra Raza. Science Experiment as Painting. April, 2017.

My friend R is a man who takes his simple pleasures seriously, so I asked him to name one for me. Boathouses, he said, without hesitation.

My friend R is a man who takes his simple pleasures seriously, so I asked him to name one for me. Boathouses, he said, without hesitation.

Early on, Magona presents readers of Beauty’s Gift with a startling image: the beautiful and ‘beloved’ Beauty laid to rest in an opulent casket, which is then fixed in the earth with cement to prevent theft. Her friends’ memories of Beauty’s charisma and kindness are concretized by the weight of her death from AIDS. From the outset, funerals emerge not merely as a plot point but a structuring device for understanding the social and political implications of the AIDS crisis in South Africa. After opening her novel with Beauty’s funeral, Magona continues with vignettes about various stages of illness, death, and grief. These include a wake, the mourning period, Beauty’s posthumous

Early on, Magona presents readers of Beauty’s Gift with a startling image: the beautiful and ‘beloved’ Beauty laid to rest in an opulent casket, which is then fixed in the earth with cement to prevent theft. Her friends’ memories of Beauty’s charisma and kindness are concretized by the weight of her death from AIDS. From the outset, funerals emerge not merely as a plot point but a structuring device for understanding the social and political implications of the AIDS crisis in South Africa. After opening her novel with Beauty’s funeral, Magona continues with vignettes about various stages of illness, death, and grief. These include a wake, the mourning period, Beauty’s posthumous

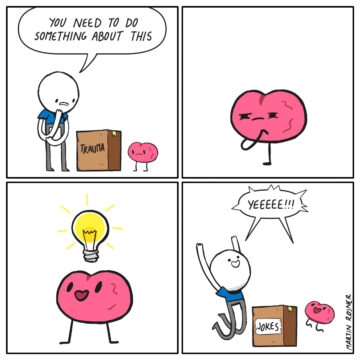

Humans are beings of staggering complexity. We don’t just consist of ourselves: billions of bacteria in our gut help with everything from digestion to immune response.

Humans are beings of staggering complexity. We don’t just consist of ourselves: billions of bacteria in our gut help with everything from digestion to immune response.

Sughra Raza. Self Portrait Against Table Mountain. August, 2019.

Sughra Raza. Self Portrait Against Table Mountain. August, 2019.

Much philosophical writing about food has included discussions of whether and why food can be a serious aesthetic object, in some cases aspiring to the level of art. These questions often turn on whether we create mental representations of flavors and textures that are as orderly and precise as the representations we form of visual objects.

Much philosophical writing about food has included discussions of whether and why food can be a serious aesthetic object, in some cases aspiring to the level of art. These questions often turn on whether we create mental representations of flavors and textures that are as orderly and precise as the representations we form of visual objects.