by Thomas R. Wells

searching bare-handed through garbage bins

in search of deposit bottles

Many environmentalists support the idea of charging deposits on drink bottles and cans in order to persuade people to bring them back for recycling. They believe this is a good and obvious way to reduce humans environmental impact.

They are mistaken.

While bottle deposit systems are superficially attractive they are a horrendously expensive way to do not much good, while also creating degrading and fundamentally worthless work for the poor. They are not the outcome of a real commitment to reducing humans’ environmental impact but of our flawed human psychology. The fundamental political attraction of bottle deposits is twofold. They appeal to voters’ underlying presumption that inflicting something mildly annoying on ourselves must be an effective means to address a problem, because the constant annoyance itself keeps in our mind that we really are doing something about it. (This resembles the folk-theory of medicine: If it tastes nasty it must be doing us good.) And bottle deposits appeal to governments’ preference for getting something for free, since all they have to do is pass a law requiring that lots of other people organise and carry out a lot of fiddly work. It’s a tax, but not one they have to justify and defend.

1. The Case for Bottle Deposits Rests on the Dubious Case for More Recycling

The implicit argument for bottle deposits goes something like this

Premise 1: Bottle deposits increase recycling rates for plastic bottles

Premise 2: When more of the products we consume are produced from recycled materials, humans’ environmental impact goes down

Premise 3: Reducing humans’ environmental impact is a good thing

Conclusion: Bottle deposits are a good thing

The problem lies with Premise 2. Recycling does not necessarily reduce environmental impact. This is because recycling has its own costs (including energy, transport, and labour costs) and toxic byproducts, which for some materials may be higher than creating products from new materials. The assumption that throwing anything away is wasteful because it is actually a valuable resource that some collective stupidity or anti-environmental capitalistic ideology is preventing us from seeing is fairly obviously false. On the contrary, as a general rule of thumb:

If someone will pay you for the item, it’s a resource. Or, if you can use the item to make something else people want, and do it at lower price or higher quality than you could without that item, then the item is also a resource. But if you have to pay someone to take it, then the item is garbage. (Michael Munger)

The key is that the case for recycling is incomplete so long as it only focuses on the benefits and excludes the full costs – including the full environmental costs – relative to other options.

When the case for recycling plastic bottles is revised to take this elementary point into account, it looks more like this.

Premise 1: Bottle deposits increase recycling rates for plastic bottles

Premise 2: Increasing recycling rates creates value if recycling these items creates more value than the best alternative

Premise 3: Recycling these items has similar or greater costs (environmental and economic) than creating new materials

Conclusion: Bottle deposits do not create value

The full cost of recycling includes the energy requirements for the transformation of formed plastics back into materials that can be used to produce new high quality items as compared to creating the same items from virgin feedstock (sourced from the oil refining process). It also includes the environmental impact of the recycling process, from transportation to the creation of toxic byproducts.

Additionally, the real cost of recycling includes the economic costs of ‘mining’ the materials: the vast amount of labour hours required for collecting and sorting different kinds of plastic and administering deposit refund systems. Just because those costs don’t show up in the relevant law, doesn’t mean they aren’t a real cost imposed on society. Resources are limited – as environmentalists are known to emphasise, quite rightly. This means that when a society expends a big chunk of its time and energies on the task of recycling, that labour is no longer available for other tasks that might create more social value (such as expanding health care or funding global poverty reduction) or even environmental value (such as funding a higher carbon tax).

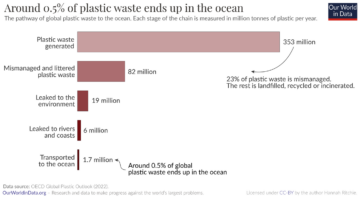

However, in this case it is not only the costs, but also the benefits of recycling that are questionable. For example, environmentalists often bewail the vast amounts of plastic that escape into the natural environment and end up in the oceans looking ugly and endangering marine animals. But there is no direct link between the choice of whether to recycle or not and the amount of plastic that ends up in the ocean.

However, in this case it is not only the costs, but also the benefits of recycling that are questionable. For example, environmentalists often bewail the vast amounts of plastic that escape into the natural environment and end up in the oceans looking ugly and endangering marine animals. But there is no direct link between the choice of whether to recycle or not and the amount of plastic that ends up in the ocean.

In order for plastics or other items discarded as trash to end up polluting the ocean, they must reach the ocean. Either consumers (or businesses) must discard their trash directly into rivers, or else the public waste collection system must do so. In countries with a properly functioning modern waste collection and disposal system (including social norms and legal enforcement of anti-littering), scarcely any plastic escapes into the oceans. Since every country contemplating a bottle-deposit scheme to reduce the amount of plastics thrown away as waste is a rich one with a fully functioning waste collection and disposal system, such schemes at their most successful will generate approximately zero reduction of the plastic pollution of the oceans. (In fact since plastic intended for recycling is often shipped to poor countries underequipped to properly recycle them, increasing recycling rates may well increase the amount of plastic entering the environment, as well as toxic chemicals that damage human and non-human health.)

2. The Creation of Dangerous and Degrading Work

The Netherlands has recently followed Germany in introducing substantial deposits on most aluminium cans and plastic bottles. Just like in Germany we now have lots of poor people rummaging through public waste bins bare-handed looking for deposit bottles that someone else missed. This is dangerous and degrading work. At great expense rich countries have recreated the job of ‘waste-picker’ familiar from documentaries about pitiful poor world slums. One consequence of this is obvious risks to the health and safety of the vulnerable and desperate people we are financially incentivising to rummage around blindly in garbage cans without any protection. Another consequence is broken garbage cans and trash strewn on the street as these same people are not especially careful and considerate of the consequences of their bottle-mining operations.

One can counter this by noting that bottle-deposit schemes provide people excluded from legal work by migration status or substance abuse problems with a way to support a bare subsistence existence in a legal way. It may look awful to have poor people trying to make a living this way, but it merely reveals a level of desperation that the smug middle-classes who run society usually manage to avoid noticing. The waste-pickers would not be doing this if they had a better option, and so they would be made even worse off if the bottle-deposits were ended.

I agree – up to a point. The creation of the economic niche of ‘waste-picking’ does not make the individuals who take it up economically worse off. But a civilised society owes it to everyone to treat them with dignity, and it is the lack of this that makes bottle-deposit schemes so disgraceful.

Firstly, to be dignified work should be worth doing. As I argued already, bottle-deposits artificially assign a financial value to returning bottles in order to motivate higher recycling collection rates. But this financial incentive does not track the real economic value of collecting plastic bottles for recycling. It seems demeaning to me to create make-work programmes for the poor where they have to rummage around in garbage to pick out worthless junk that costs more to recycle than to make new. There are far more effective ways to help the poor that also demonstrate our respect for their fundamentally equal human dignity. For example, why not pay them cash to pick up the litter on the actual streets?

Second, workers themselves deserve to be treated with dignity within their work. If a rich society reinvents waste-picking, even if that was not its intention, then it should take responsibility for the character of the work it creates. Waste-pickers deserve personal protective equipment; clean hard-wearing clothes to work in; OSHA type protections against poorly designed – unnecessarily dangerous – work environments; some kind of workers compensation insurance system; and so on.

3. Bottle Deposits Are Better Politics Than Genuine Environmentalism

Bottle deposits seem a strangely ineffective means for addressing the environmental problems that ostensibly motivate them.

If the problem is excessive resource consumption (such as the 6% or so of oil production that goes to making plastics) then a direct tax on those resources seems the obvious way to persuade companies to find ways to use less of them, and to make their products more recyclable. Not a weird refundable tax on certain kinds of drinks containers.

Likewise, if the problem is excessive greenhouse gas emissions, associated with energy intensive industrial processes like those that produce plastics, then tax energy use and use the proceeds to subsidise the development, scaling, and diffusion of less energy intensive industrial technologies.

If you want less trash – plastic or otherwise – to escape into the oceans and rivers, then invest more in better waste-management systems, especially in poorer countries. If you want trash not to persist in the environment, or not to leak dangerous chemicals, then the solutions would seem to involve requiring packaging to be made of biodegradable materials and banning toxic additives.

What happens to drinks bottles in rich countries is basically irrelevant to any of these problems, and so anything directed specifically at collecting more of them seems pretty pointless. So why are they so popular?

I have a theory. Environmental guilt is high. Various activists have tried to exploit this to support substantial political action to protect features of the natural world from degradation and the climate from greenhouse gas emissions. But various political entrepreneurs have seen more profitable ways to exploit environmental guilt to sell policies that appeal to those feelings of guilt without actually protecting the environment in any meaningful way. (Various other political entrepreneurs have seen the opportunity to exploit the cognitive dissonance triggered by environmental guilt itself by selling denialism.) So goes the market for junk ideas in a democracy: Actual governance is hard work demanding competence and dedication, but selling the appearance of being a champion of some cause or other is easy.

Bottle deposits is an example of such a junk idea. It gains political traction from the peculiarities of political psychology rather than its qualities for addressing the fundamental problem of humans’ excessive impact on our environment, and it causes additional harms as well.

Ironically, recycling our drinks bottles doesn’t necessarily make us feel better. It doesn’t allow us to feel free of environmental guilt. Actually it probably makes us feel worse by keeping that sense of guilt always in our mind. But it does make us feel like we are acting in the right way in response to that moral guilt. Like dieting, it doesn’t work either as a means of losing weight or as a means of escaping the guilty feeling that one ought to lose weight, but it nevertheless captures an awful lot of people’s time, money, and attention and reorients a whole society’s understanding of the problem in unhelpful ways.

Thomas Wells teaches philosophy in the Netherlands and blogs at The Philosopher’s Beard

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.