by Gus Mitchell

The following piece is my own minor contribution to the “Surrealism Centenary.” I begin with a disavowal of the entire “2024 centenary” enterprise, which seems to have added little to our appreciation of the group, and because I would question allowing Andre Breton, great though he sometimes was, to continue to define the wildly heterodox big bang to which he claimed total definition in October 1924.

Let us begin to celebrate the spirit of the surreal again. True to that spirit, let us slough off the burden of officialism and of art history. Let us not be bound to Breton or (heaven help us) Dali any longer.

This year should begin an overhaul of correction to the Anglophone ignorance of the movement’s noblest, most enduring, and still-dangerous representatives, who always were the outcasts, misfits, and weirdos among those proudly self-proclaimed outcasts, misfits, and weirdos.

Of these, a host of obscurer names and out of print-translations can be dug into online.

What I outline here is merely my favourite example.

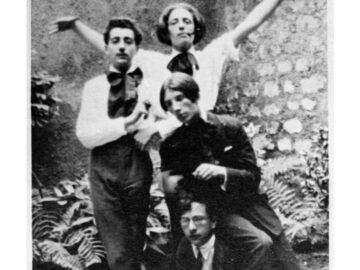

In the 1910s, a quartet of teenaged artistic comrades in provincial France––Rene Daumal, Robert Gilbert-Lecompte, novelist Roger Vailland and Robert Meyrat––began a drug-fuelled quest into what they termed “experimental metaphysics”. After forming something of an adolescent secret society/artistic movement (which they dubbed Simplisme) this core quartet moved to Paris, made some older acquaintances and formed a short-lived journal: Le Grand Jeu (The Great Game) of which only three issues appeared, between 1928 and 1932. (The essence of this work and an essential English handbook to the group can be found in the English translation Theory of the Great Game, edited by Dennis Duncan, pictured above.) Read more »

Renowned and respected for her scholarship, her history of authorship of many books on dictatorship and her political experience, is it any wonder that Anne Applebaum’s new book Autocracy, Inc. The Dictators Who Want to Run the World has been so critically received; she is an expert on her subject. This slim volume provides us with an incisive exposition and analysis of how autocrats function in the world today, securing their own personal power and wealth, and in Applebaum’s view, posing a threat to democracies.

Renowned and respected for her scholarship, her history of authorship of many books on dictatorship and her political experience, is it any wonder that Anne Applebaum’s new book Autocracy, Inc. The Dictators Who Want to Run the World has been so critically received; she is an expert on her subject. This slim volume provides us with an incisive exposition and analysis of how autocrats function in the world today, securing their own personal power and wealth, and in Applebaum’s view, posing a threat to democracies.

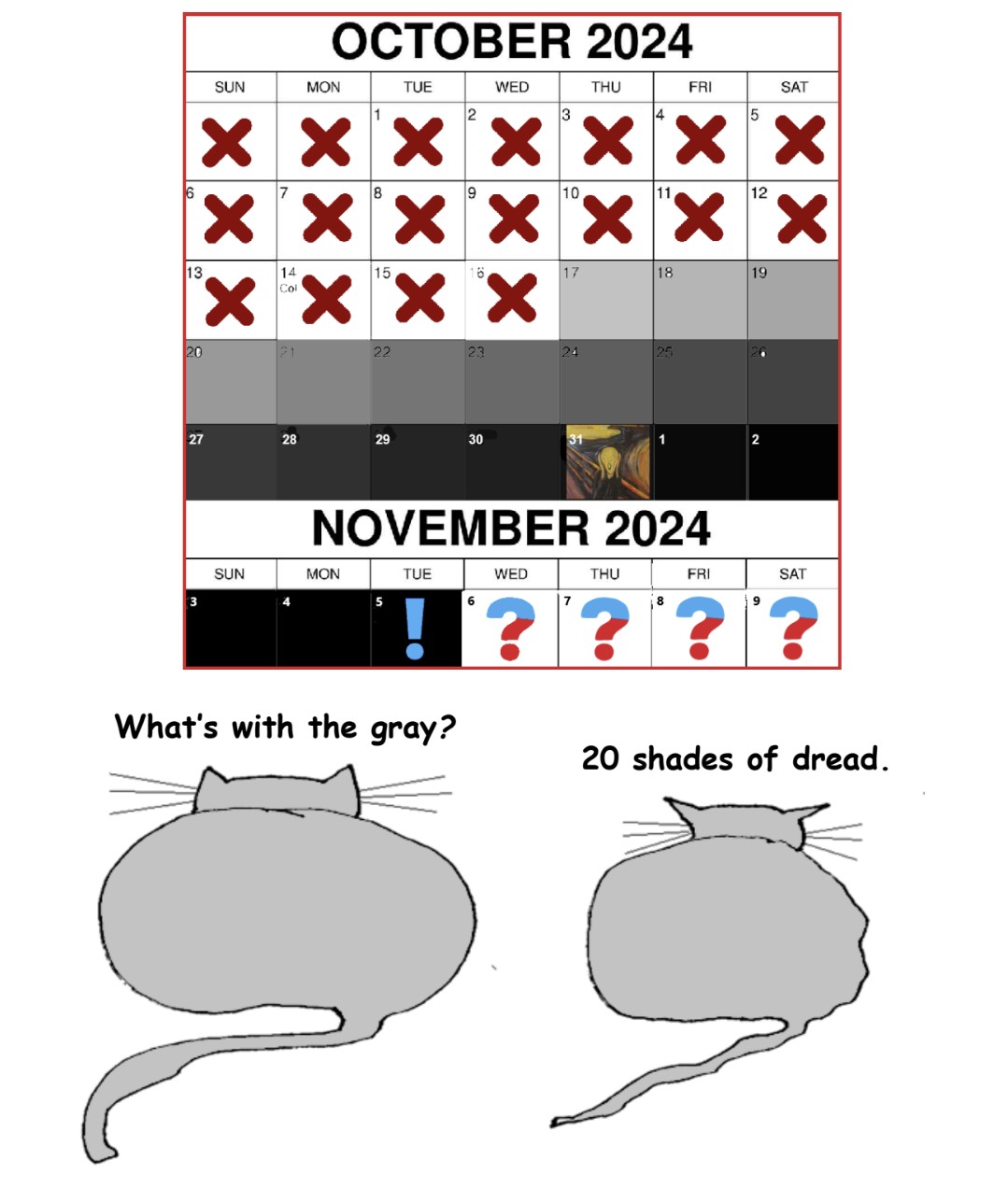

Every time I read or watch anything about the election I hear some variant of the phrase “margin of error.” My mathematically attuned ears perk up, but usually it’s just a slightly pretentious way of saying the election is very close or else that it’s not very close. Schmargin of error might be a better name for metaphorical uses of the phrase.

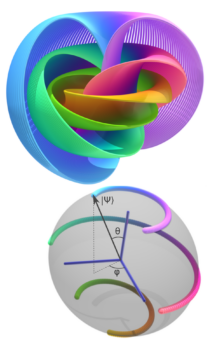

Every time I read or watch anything about the election I hear some variant of the phrase “margin of error.” My mathematically attuned ears perk up, but usually it’s just a slightly pretentious way of saying the election is very close or else that it’s not very close. Schmargin of error might be a better name for metaphorical uses of the phrase. Philosophical reflection on artificial intelligence (AI) has been a feature of the early days of cybernetics, with Alan Turing’s famous proposals on the notion of intelligence in the 1950s rearming old philosophical debates on the man-system or man-machine and the possibly mechanistic nature of cognition. However, AI raises questions on spheres of philosophy with the contemporary advent of connectionist artificial intelligence based on deep learning through artificial neural networks and the prodigies of generative foundation models. One of the most prominent examples is the philosophy of mind, which seeks to reflect on the benefits and limits of a computational approach to mind and consciousness. Other spheres of affected philosophies are ethics, which is confronted with original questions on agency and responsibility; political philosophy, which is obliged to think afresh about augmented action and algorithmic governance; the philosophy of language; the notion of aesthetics, which has to take an interest in artistic productions emerging from the latent spaces of AIs and where its traditional categories malfunction; and metaphysics, which has to think afresh about the supposed human exception or the question of finitude.

Philosophical reflection on artificial intelligence (AI) has been a feature of the early days of cybernetics, with Alan Turing’s famous proposals on the notion of intelligence in the 1950s rearming old philosophical debates on the man-system or man-machine and the possibly mechanistic nature of cognition. However, AI raises questions on spheres of philosophy with the contemporary advent of connectionist artificial intelligence based on deep learning through artificial neural networks and the prodigies of generative foundation models. One of the most prominent examples is the philosophy of mind, which seeks to reflect on the benefits and limits of a computational approach to mind and consciousness. Other spheres of affected philosophies are ethics, which is confronted with original questions on agency and responsibility; political philosophy, which is obliged to think afresh about augmented action and algorithmic governance; the philosophy of language; the notion of aesthetics, which has to take an interest in artistic productions emerging from the latent spaces of AIs and where its traditional categories malfunction; and metaphysics, which has to think afresh about the supposed human exception or the question of finitude. The opening credits of Affliction (1997) feature small, rectangular images that fill only half the screen. You wonder if something is wrong with the aspect ratio, or if the settings have been changed on your television. A succession of images is placed before the viewer: a farmhouse in a snowy field, a trailer with a police cruiser parked in front, the main street of a small, sleepy town, the schoolhouse, the town hall. The last image is a dark, rural road, with a mountain in the distance. Finally the edges of the image expand, fill the screen, and a voice begins to narrate:

The opening credits of Affliction (1997) feature small, rectangular images that fill only half the screen. You wonder if something is wrong with the aspect ratio, or if the settings have been changed on your television. A succession of images is placed before the viewer: a farmhouse in a snowy field, a trailer with a police cruiser parked in front, the main street of a small, sleepy town, the schoolhouse, the town hall. The last image is a dark, rural road, with a mountain in the distance. Finally the edges of the image expand, fill the screen, and a voice begins to narrate:

Egypt

Egypt Germany

Germany

In her provocative, genre-defying book,

In her provocative, genre-defying book,