by David J. Lobina

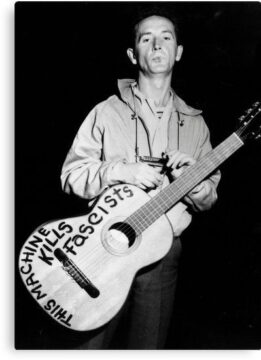

Firstly: fascism is dead and it is not coming back. By fascism it is meant the historical fascism of the 1920-40s, in particular the primus inter (more-or-less) pares fascism of 1920s Italy – id est, Fascism – and to a lesser extent that of Nazi Germany, notwithstanding the fact that Nazism is different to Fascism in some important respects, as stressed before in these very pages – alas not being the case here, secondes pensées sont (often) les bonnes.

Secondly: this is not our opinion alone, but that of both Umberto Eco, explicitly stated so in his little note on fascism, and Pier Paolo Pasolini, the latter saying so-so in a little-known pamphlet by the title of Il fascismo degli antifascisti. For the latter author, historical fascism was the traditional or archaeological kind, an archaic fascism that did not exist any more at the time of writing (circa 1960-1975) and should not be confused with the fascism that 1960-70s kids kept denouncing, and the Owen Joneses of the 2020s keep denouncing, this milieu then and now forming an archaeological antifascism that is rather comfortable, as Pasolini put it then. For the former author, in turn, historical fascism was the original kind, and also dead, but there was a warning therein: an eternal fascism can be unearthed in terms of the fascist ‘way of talking and feeling’ – the linguistic habits of fascism.

Thirdly: what the Eco of the little note was most concerned about was the then contemporary developments in Italian politics that had brought a post-fascist political party into government in 1994. In this note Eco listed a number of features encompassing what may be termed a fascist temperament, a loose connection of features that has received little attention in the scholarship on fascism – the world of the discretus et sapiens – but an outsized interest elsewhere. Eco did not envision this list as a set of necessary or sufficient conditions to define fascism; nothing so unambitious: one single feature sufficed ‘to allow fascism to coagulate around it’, a sentiment widely echoed today.

Fourthly: Fascism, however, is not a way of talking or feeling, or a temperament, let alone an eternal phenomenon, in the same way that there is no eternal communism, or a communist way of talking or feeling; no eternal liberalism, or a liberal way of talking or feeling; no eternal anarchism, or an anarchist way of talking or feeling. The Okhrana is reputed to have dismissed the stereotypically-looking revolutionaries, and rightly so; the same applies, mutatis mutandis, in the state of affairs being surveyed by our telescope. Read more »

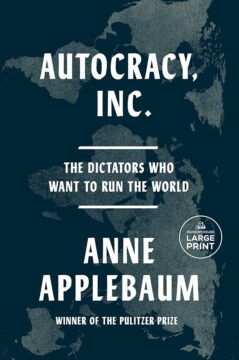

Renowned and respected for her scholarship, her history of authorship of many books on dictatorship and her political experience, is it any wonder that Anne Applebaum’s new book Autocracy, Inc. The Dictators Who Want to Run the World has been so critically received; she is an expert on her subject. This slim volume provides us with an incisive exposition and analysis of how autocrats function in the world today, securing their own personal power and wealth, and in Applebaum’s view, posing a threat to democracies.

Renowned and respected for her scholarship, her history of authorship of many books on dictatorship and her political experience, is it any wonder that Anne Applebaum’s new book Autocracy, Inc. The Dictators Who Want to Run the World has been so critically received; she is an expert on her subject. This slim volume provides us with an incisive exposition and analysis of how autocrats function in the world today, securing their own personal power and wealth, and in Applebaum’s view, posing a threat to democracies.

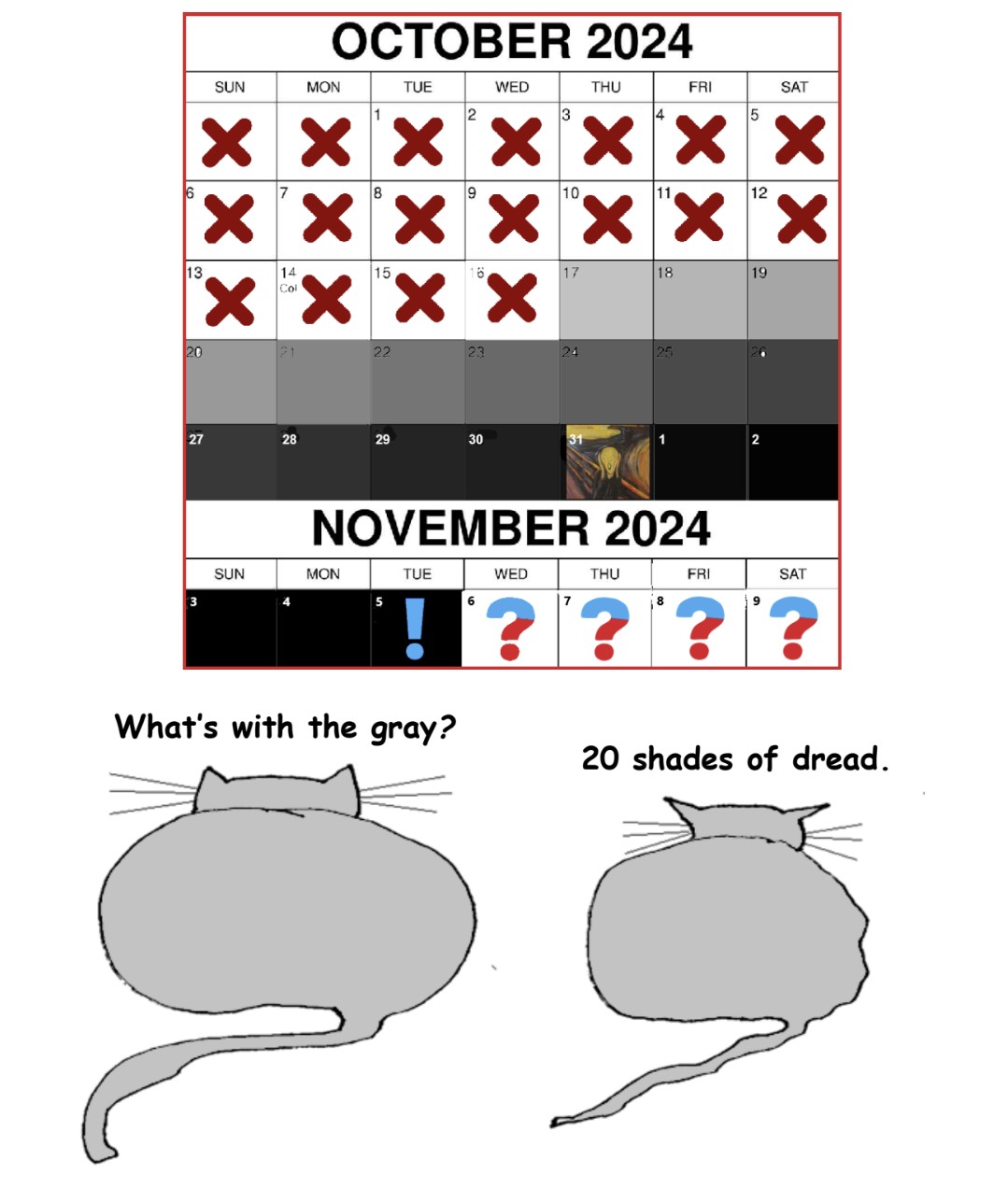

Every time I read or watch anything about the election I hear some variant of the phrase “margin of error.” My mathematically attuned ears perk up, but usually it’s just a slightly pretentious way of saying the election is very close or else that it’s not very close. Schmargin of error might be a better name for metaphorical uses of the phrase.

Every time I read or watch anything about the election I hear some variant of the phrase “margin of error.” My mathematically attuned ears perk up, but usually it’s just a slightly pretentious way of saying the election is very close or else that it’s not very close. Schmargin of error might be a better name for metaphorical uses of the phrase. Philosophical reflection on artificial intelligence (AI) has been a feature of the early days of cybernetics, with Alan Turing’s famous proposals on the notion of intelligence in the 1950s rearming old philosophical debates on the man-system or man-machine and the possibly mechanistic nature of cognition. However, AI raises questions on spheres of philosophy with the contemporary advent of connectionist artificial intelligence based on deep learning through artificial neural networks and the prodigies of generative foundation models. One of the most prominent examples is the philosophy of mind, which seeks to reflect on the benefits and limits of a computational approach to mind and consciousness. Other spheres of affected philosophies are ethics, which is confronted with original questions on agency and responsibility; political philosophy, which is obliged to think afresh about augmented action and algorithmic governance; the philosophy of language; the notion of aesthetics, which has to take an interest in artistic productions emerging from the latent spaces of AIs and where its traditional categories malfunction; and metaphysics, which has to think afresh about the supposed human exception or the question of finitude.

Philosophical reflection on artificial intelligence (AI) has been a feature of the early days of cybernetics, with Alan Turing’s famous proposals on the notion of intelligence in the 1950s rearming old philosophical debates on the man-system or man-machine and the possibly mechanistic nature of cognition. However, AI raises questions on spheres of philosophy with the contemporary advent of connectionist artificial intelligence based on deep learning through artificial neural networks and the prodigies of generative foundation models. One of the most prominent examples is the philosophy of mind, which seeks to reflect on the benefits and limits of a computational approach to mind and consciousness. Other spheres of affected philosophies are ethics, which is confronted with original questions on agency and responsibility; political philosophy, which is obliged to think afresh about augmented action and algorithmic governance; the philosophy of language; the notion of aesthetics, which has to take an interest in artistic productions emerging from the latent spaces of AIs and where its traditional categories malfunction; and metaphysics, which has to think afresh about the supposed human exception or the question of finitude. The opening credits of Affliction (1997) feature small, rectangular images that fill only half the screen. You wonder if something is wrong with the aspect ratio, or if the settings have been changed on your television. A succession of images is placed before the viewer: a farmhouse in a snowy field, a trailer with a police cruiser parked in front, the main street of a small, sleepy town, the schoolhouse, the town hall. The last image is a dark, rural road, with a mountain in the distance. Finally the edges of the image expand, fill the screen, and a voice begins to narrate:

The opening credits of Affliction (1997) feature small, rectangular images that fill only half the screen. You wonder if something is wrong with the aspect ratio, or if the settings have been changed on your television. A succession of images is placed before the viewer: a farmhouse in a snowy field, a trailer with a police cruiser parked in front, the main street of a small, sleepy town, the schoolhouse, the town hall. The last image is a dark, rural road, with a mountain in the distance. Finally the edges of the image expand, fill the screen, and a voice begins to narrate:

Egypt

Egypt Germany

Germany