MORE LOOPY LOONIES BY ANDREA SCRIMA

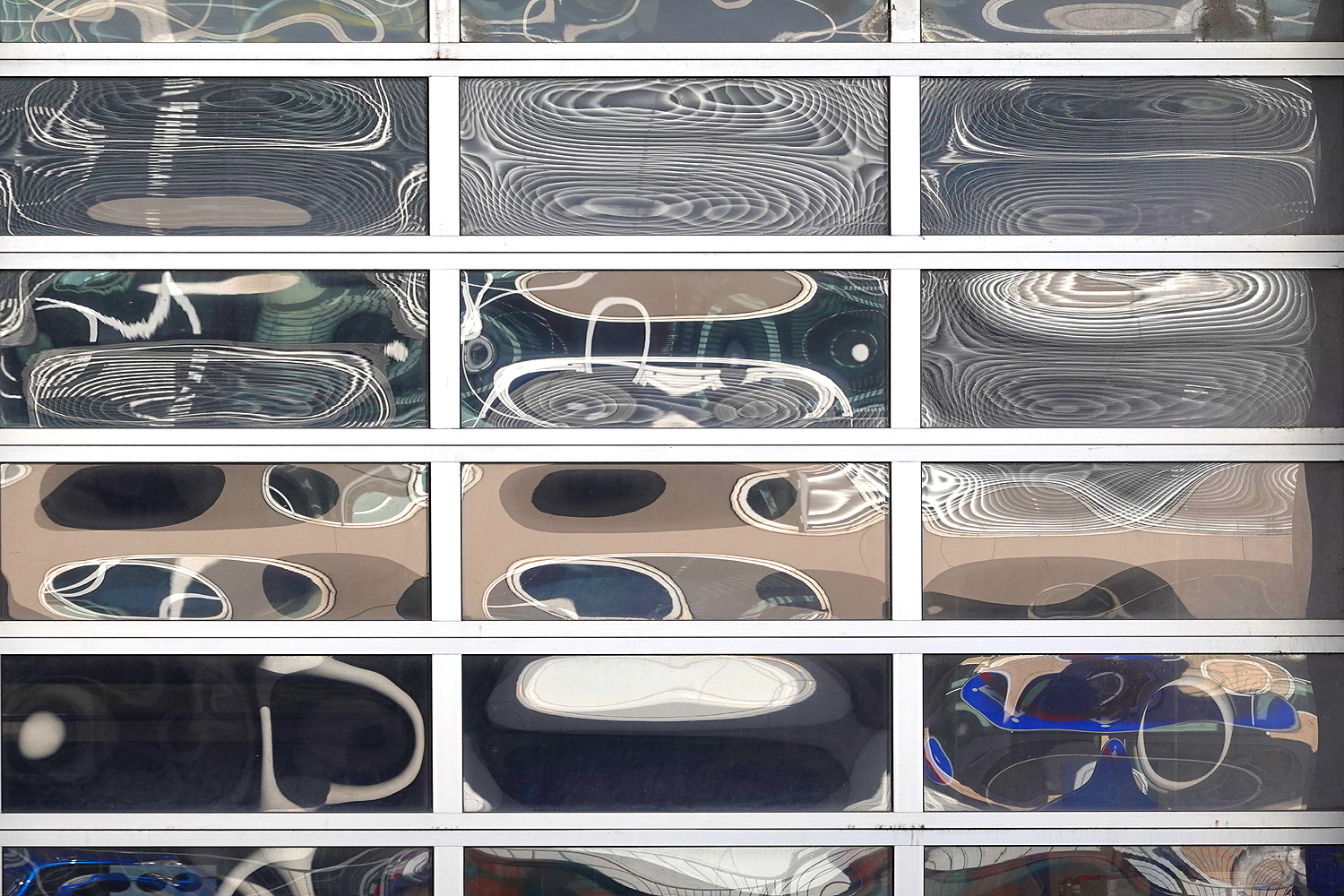

For the past ten years, Andrea Scrima has been working on a group of drawings entitled LOOPY LOONIES. The result is a visual vocabulary of splats, speech bubbles, animated letters, and other anthropomorphized figures that take contemporary comic and cartoon images and the violence imbedded in them as their point of departure. Against the backdrop of world political events of the past several years—war, pandemic, the ever-widening divisions in society—the drawings spell out words such as NO (an expression of dissent), EWWW (an expression of disgust), OWWW (an expression of pain), or EEEK (an expression of fear). The morally critical aspects of Scrima’s literary work take a new turn in her art and vice versa: a loss of words is countered first with visual and then with linguistic means. Out of this encounter, a series of texts ensue that explore topics such as the abuse of language, the difference between compassion and empathy, and the nature of moral contempt and disgust.

Part I of this project can be seen and read HERE

Part II of this project can be seen and read HERE

Images from the exhibition LOOPY LOONIES at Kunsthaus Graz, Austria, can be seen HERE

7. EEEK

Michel de Montaigne’s famous statement—“The thing I fear most is fear”—remains, nearly five hundred years later, thoroughly modern. We think of fear as an illusion, a mental trap of some kind, and believe that conquering it is essential to our personal well-being. Yet in evolutionary terms, fear is an instinctive response grounded in empirical observation and experience. Like pain, its function is self-preservation: it alerts us to the threat of very real dangers, whether immediate or imminent.

Fear can also be experienced as an indistinct existential malaise, deriving from the knowledge that misfortune inevitably happens, that we will one day die, and that prior to our death we may enter a state so weak and vulnerable that we can no longer ward off pain and misery. We think of this more generalized fear as anxiety: we can’t shake the sense that bad things—the vagueness of which render them all the more frightening—are about to befall us. The world is an inherently insecure and precarious place; according to Thomas Hobbes, “there is no such thing as perpetual Tranquillity of mind, while we live here; because life it selfe is but Motion, and can never be without Desire, nor without Fear” (Leviathan, VI). Day by day, we are confronted with circumstances that justify a response involving some degree of entirely realistic and reasonable dread and apprehension, yet anxiety is classified as a psychological disorder requiring professional therapeutic treatment. Read more »

Everyone grieves in their own way. For me, it meant sifting through the tangible remnants of my father’s life—everything he had written or signed. I endeavored to collect every fragment of his writing, no matter profound or mundane – be it verses from the Quran or a simple grocery list. I wanted each text to be a reminder that I could revisit in future. Among this cache was the last document he ever signed: a do-not-resuscitate directive. I have often wondered how his wishes might have evolved over the course of his life—especially when he had a heart attack when I was only six years old. Had the decision rested upon us, his children, what path would we have chosen? I do not have definitive answers, but pondering on this dilemma has given me questions that I now have to revisit years later in the form of improving ethical decision making at the end-of-life scenarios. To illustrate, consider Alice, a fifty-year-old woman who had an accident and is incapacitated. The physicians need to decide whether to resuscitate her or not. Ideally there is an

Everyone grieves in their own way. For me, it meant sifting through the tangible remnants of my father’s life—everything he had written or signed. I endeavored to collect every fragment of his writing, no matter profound or mundane – be it verses from the Quran or a simple grocery list. I wanted each text to be a reminder that I could revisit in future. Among this cache was the last document he ever signed: a do-not-resuscitate directive. I have often wondered how his wishes might have evolved over the course of his life—especially when he had a heart attack when I was only six years old. Had the decision rested upon us, his children, what path would we have chosen? I do not have definitive answers, but pondering on this dilemma has given me questions that I now have to revisit years later in the form of improving ethical decision making at the end-of-life scenarios. To illustrate, consider Alice, a fifty-year-old woman who had an accident and is incapacitated. The physicians need to decide whether to resuscitate her or not. Ideally there is an

Monica Rezman. After Dark. 2023. (“this is what it’s like to live in the tropics”)

Monica Rezman. After Dark. 2023. (“this is what it’s like to live in the tropics”)

Close-Up, a 1990 Iranian film directed by Abbas Kiarostami, is one of the rare films where the viewing experience is enhanced by knowing certain details beforehand.

Close-Up, a 1990 Iranian film directed by Abbas Kiarostami, is one of the rare films where the viewing experience is enhanced by knowing certain details beforehand.