by Ed Simon

Impossible to know which one of those perennial evergreen subjects – love or death – poetry considers more, but certainly verse can be particularly charged when it combines those two. Love and death, the only topics worthy of serious contemplation, where anything else worth orienting the mind towards is merely an amalgamation of that pair. Maybe that seems counterintuitive, or worse still as mere sophistry, to claim that love and death are ineffable in the manner of God, for after all there are clear definitions of love and death, and furthermore everyone has an experience of them. But it’s their universality that makes them ineffable, because both are defined by paradox. Death, after all, is the one commonality to all of life, the only thing that absolutely every person will experience, but also that which nobody currently alive can say anything definitive about. A paradox, death. Love, though sadly not as universal as death, would seem to be less paradoxical, and yet genuine love is marked by a desire for personal extinction (not unlike death), a submerging of the self into the being of another. An arithmetic not of addition, but of multiplication. Of one and one equaling one.

In American modernist Edna St. Vincent Millay’s effecting “Dirge Without Music,” a free verse four-quatrain poem written in an alternate rhyme scheme that evokes a ballad first published in 1928, death is read in light of love in a manner that provides a glimpse of comprehension as regards those things which are ineffable. Her poem explores the tensions in love and death, not least of all in the title of the poem which is a paradox. A dirge, by definition, is composed of music, so that to have a dirge without music is nonsensical, like a sculpture without shape or a story without narrative. Yet that’s also precisely what death is, an experience of life – perhaps the sine qua non of life which gives it meaning – but also something that can’t be experienced in life since it marks the termination of existence. That particular aspect of death has long been remarked upon, a favored argument of the Stoics and Epicureans in ancient Greece meant as a comfort regarding the fear of extinction. Such an argument maintains that if eternity follows death than the later isn’t really death, and if death is marked by the obliteration of the self than we never really experience it, since experience requires a self. All well and good in terms of the logic, but not quite adequate to the phenomenological question of what death feels like, for what does it mean to experience something defined by an inability to feel (as if listening to a dirge without music)? Read more »

Sughra Raza. Reflection. Merida, Yucatan, March 14, 2025.

Sughra Raza. Reflection. Merida, Yucatan, March 14, 2025.

Everyone grieves in their own way. For me, it meant sifting through the tangible remnants of my father’s life—everything he had written or signed. I endeavored to collect every fragment of his writing, no matter profound or mundane – be it verses from the Quran or a simple grocery list. I wanted each text to be a reminder that I could revisit in future. Among this cache was the last document he ever signed: a do-not-resuscitate directive. I have often wondered how his wishes might have evolved over the course of his life—especially when he had a heart attack when I was only six years old. Had the decision rested upon us, his children, what path would we have chosen? I do not have definitive answers, but pondering on this dilemma has given me questions that I now have to revisit years later in the form of improving ethical decision making at the end-of-life scenarios. To illustrate, consider Alice, a fifty-year-old woman who had an accident and is incapacitated. The physicians need to decide whether to resuscitate her or not. Ideally there is an

Everyone grieves in their own way. For me, it meant sifting through the tangible remnants of my father’s life—everything he had written or signed. I endeavored to collect every fragment of his writing, no matter profound or mundane – be it verses from the Quran or a simple grocery list. I wanted each text to be a reminder that I could revisit in future. Among this cache was the last document he ever signed: a do-not-resuscitate directive. I have often wondered how his wishes might have evolved over the course of his life—especially when he had a heart attack when I was only six years old. Had the decision rested upon us, his children, what path would we have chosen? I do not have definitive answers, but pondering on this dilemma has given me questions that I now have to revisit years later in the form of improving ethical decision making at the end-of-life scenarios. To illustrate, consider Alice, a fifty-year-old woman who had an accident and is incapacitated. The physicians need to decide whether to resuscitate her or not. Ideally there is an

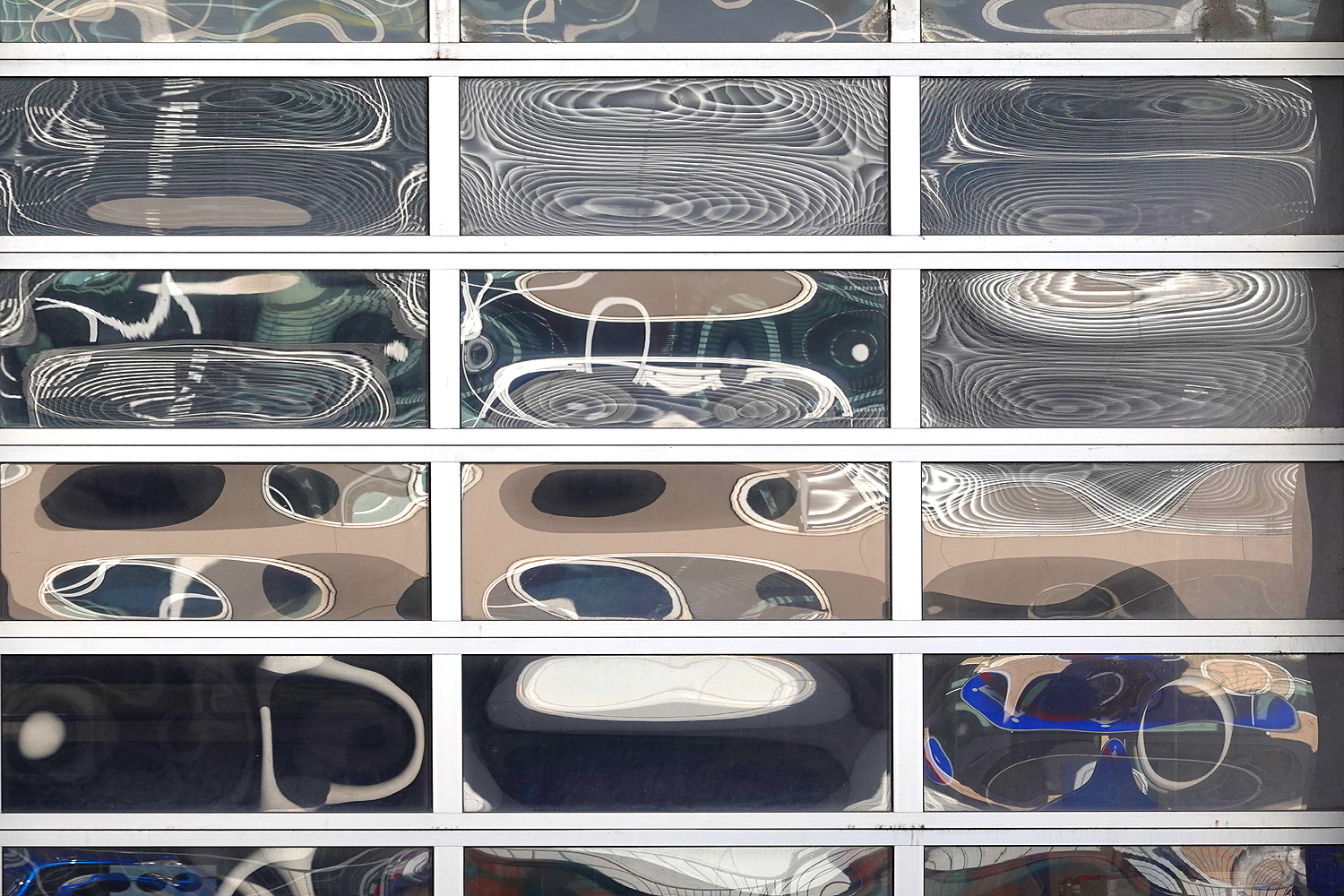

Monica Rezman. After Dark. 2023. (“this is what it’s like to live in the tropics”)

Monica Rezman. After Dark. 2023. (“this is what it’s like to live in the tropics”)