by Jochen Szangolies

Stephen King’s Dark Tower-series takes place in a world that has ‘moved on’, and appears to be deteriorating. The story’s main protagonist, Roland Deschain, last of an ancient, knight-like order of gunslingers, is seeking the titular Dark Tower, which forms a sort of nexus of all realities, to perhaps halt or even reverse the decay. His greatest fear is that once he reaches the top of the tower, he finds it empty: God or whatever force is supposed to preside over the multiverse dead, or absent, or perhaps never having existed in the first place.

There is substantive debate on what forces shape history: the actions of great leaders, the will of the people, material conditions, conflict, or perhaps other forces entirely. For our purposes, however, we can group these into two categories: the microcausal view, where history is nothing but the sum total of millions upon millions of individual actions, and the macrocausal view, where there exists some form of overarching driver of history, be it fate, a Hegelian world spirit, or some form of laws of history that dictate its unfolding. This second option is perhaps most simply explained by there being an occupant to the room at the top of the Dark Tower: some entity that, by whatever means or design, holds the reins and shapes the course of the world.

In today’s world, this is a less widely held opinion than might have once been the case. But does this mean that history is just comprised of actions at the individual level, and it is thus this level that we should best appeal to for explanatory force? Is there, as Margaret Thatcher claimed, ‘no such thing as society’?

My aim in this column is to investigate the possibility that there is a middle being excluded here. Just as the theory of evolution has shown us that there can be design without a designer, I propose that, at least in certain respects, there can be a sort of ‘plan’ without a planner to history—that, in other words, it can make sense to analyze its course as if it were following a design not reducible to the actions of individuals. Read more »

groups of citizens. Let’s call them the Shirts and the Skins. The Shirts believe homosexuality is an abomination that stinketh in the nostrils of the Lord, and abortion is baby murder. The Skins believe homosexuality is perfectly normal and natural, and abortion is a woman’s right. How can we build a society where those groups can get along without killing each other?

groups of citizens. Let’s call them the Shirts and the Skins. The Shirts believe homosexuality is an abomination that stinketh in the nostrils of the Lord, and abortion is baby murder. The Skins believe homosexuality is perfectly normal and natural, and abortion is a woman’s right. How can we build a society where those groups can get along without killing each other?

Sughra Raza. Decay Saturated. Vermont, April, 2017.

Sughra Raza. Decay Saturated. Vermont, April, 2017. If you in any way follow AI policy, you will likely have heard that the EU AI Act’s Code of Practice (CoP) was released on July 10. This is one of the major developments in AI policy this year. 2025 has otherwise been fairly negative for AI safety and risk – the Paris AI summit in February

If you in any way follow AI policy, you will likely have heard that the EU AI Act’s Code of Practice (CoP) was released on July 10. This is one of the major developments in AI policy this year. 2025 has otherwise been fairly negative for AI safety and risk – the Paris AI summit in February

I write this not to counter Holocaust deniers. That would be a waste of time; the criminally insane will spew their fantastical vitriol no matter what you tell them. Nor do I write this in the spirit of “Never forget!” As a historian I am committed to remembering this and many more genocides, particularly the most devastating and thorough genocide of all: the European genocides of Indigenous societies. At the same time, I understand the ultimate futility of admirable slogans such as “Never Forget!” For everything is forgotten, eventually. Everything and everyone.

I write this not to counter Holocaust deniers. That would be a waste of time; the criminally insane will spew their fantastical vitriol no matter what you tell them. Nor do I write this in the spirit of “Never forget!” As a historian I am committed to remembering this and many more genocides, particularly the most devastating and thorough genocide of all: the European genocides of Indigenous societies. At the same time, I understand the ultimate futility of admirable slogans such as “Never Forget!” For everything is forgotten, eventually. Everything and everyone.

In reading about attachment theory,

In reading about attachment theory,

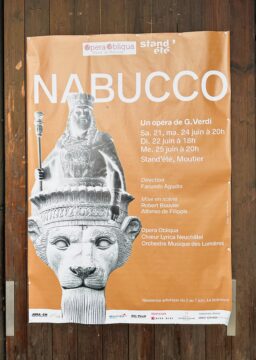

On a sunny Saturday towards the end of last month we took a train to Moutier in the west of Switzerland, half an hour from the French border, to attend an opera in a shooting range. We had tickets to hear my friend

On a sunny Saturday towards the end of last month we took a train to Moutier in the west of Switzerland, half an hour from the French border, to attend an opera in a shooting range. We had tickets to hear my friend